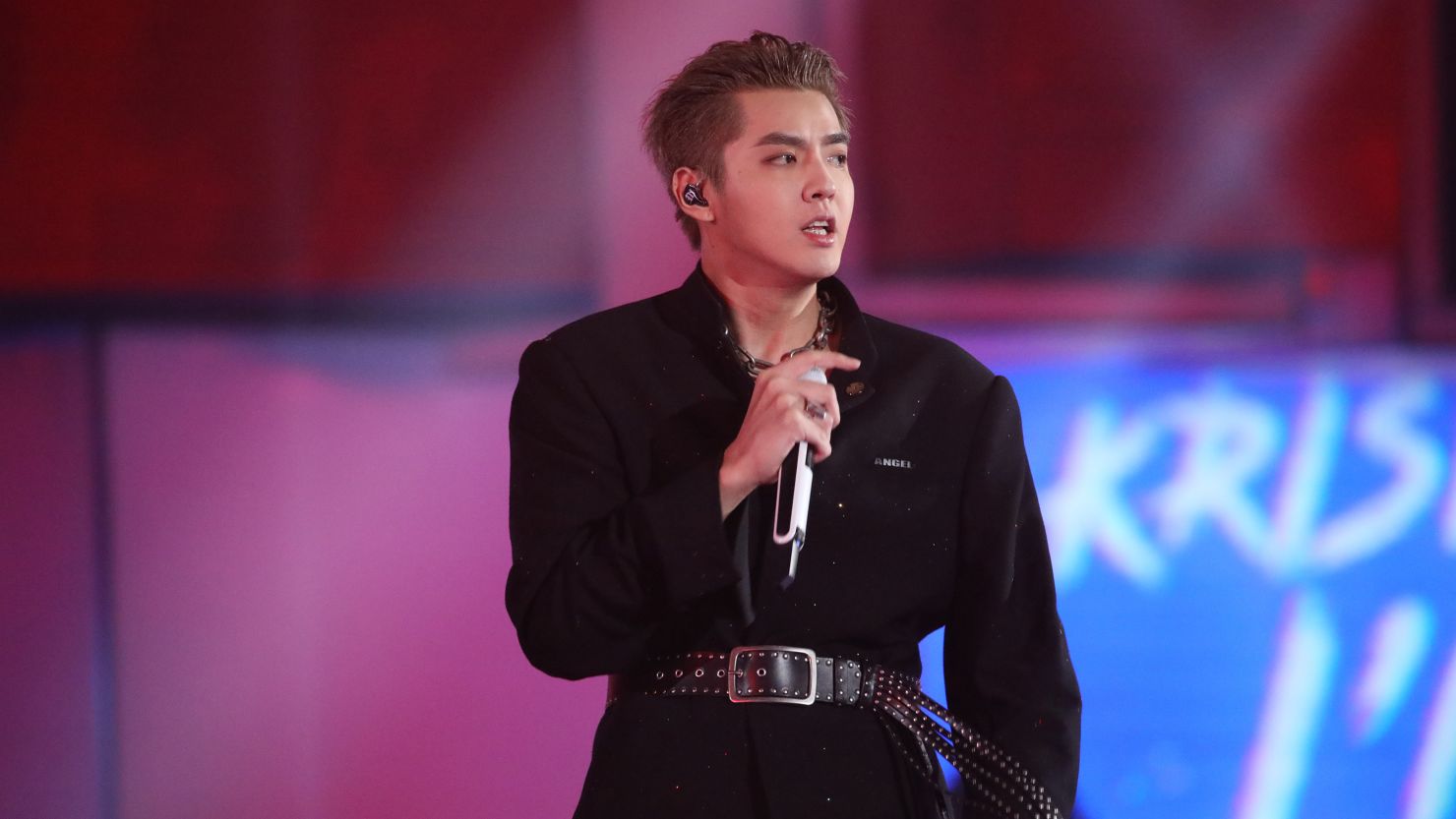

Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu has been formally arrested on suspicion of rape, prosecutors in Beijing said in a statement Monday.

The move comes after 30-year-old Wu was first detained on July 31 by police in the Chinese capital, following an online outcry over sexual assault allegation against him in what has become the most high-profile #Metoo case in China.

The allegations first emerged last month on Chinese social media platform Weibo, when a woman posting under the verified handle “Du Meizhu” alleged Wu, whose Chinese name is Wu Yifan, had sexually assaulted her while she was drunk at the pop star’s home, where she said she had gone for a casting interview.

The woman, a student at the Communication University of China in Beijing, said she was 17 at the time of the alleged assault.

Du later alleged that several other women, including two minors, had reached out to her to share similar experiences of being lured into having sex by Wu, who is one of China’s biggest stars.

Wu’s representatives did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

The terse statement from the prosecutor’s office in Beijing’s Chaoyang said Wu’s arrest for suspected rape was formally approved Monday, but it did not offer any details on the charges.

Before he was detained, Wu had denied the allegations on his personal Weibo account. His company said it was pursuing legal action against his accuser, calling the accusations “malicious rumors.”

Wu, who was born in southern China but is a Canadian citizen, rose to fame as a member of popular Korean-Chinese pop group EXO, then as a solo act after he left the band in 2014. He starred in multiple movies and modeled for brands like Burberry, soon becoming one of the country’s top brand ambassadors.

But many of his biggest brand partners were quick to distance themselves as the rape allegations spread in July. French fashion house Louis Vuitton, Italian luxury brand Bulgari and Chinese cosmetics brand Kans were among those that suspended or severed ties completely with the star.

Wu’s dramatic downfall only accelerated after his detention. His once wildly popular social media accounts, including his Weibo page with more than 51 million followers, were taken down overnight. His songs were also removed from music streaming sites.

On Monday evening, Wu’s arrest became the top trending topic on Weibo, with most comments supporting the police action. A related Weibo hashtag has been viewed 1.6 billion times as of Tuesday morning.

China’s #MeToo movement

Wu’s case is not the only #Metoo scandal that has rocked China in recent weeks. Last Monday, the e-commerce giant Alibaba said it had fired an employee who was accused of sexually assaulting another employee during a business trip.

In both cases, victims had posted their allegations on Chinese social media, which sparked an online furor and prompted police to investigate.

The authorities’ swift actions won praise from some online, who pointed to the two cases as an indication of the effective rule of law and criminal justice in China. Yet it raised eyebrows among others, who argued the high-profile nature of the cases served to highlight how rare it is for survivors to speak out and seek justice.

“It is unsurprising that both cases have drawn such wide attention, given (Kris Wu) and Alibaba’s high profile,” said Feng Yuan, a feminist scholar and activist. “But this also serves as a reminder that for many other cases of sexual harassment and assault, if the accused are not so famous or influential, (victims) might not have their voices heard at all.”

Sexual assault survivors have long faced strong stigma and resistance in China, at the official level as well as among the public.

The issue was pushed to the fore in 2018 when the #MeToo movement went global. In China, too, it prompted more women to share their experiences with sexual misconduct and assault – but the movement was quickly quashed, as the government moved to block growing online discussion, including censoring the hashtag and many related posts.

Activists say the recent cases show the government is still reluctant to discuss sexual misconduct as a systemic problem, instead preferring to report on individual cases and cast blame elsewhere.

For instance, a government watchdog agency said the Kris Wu case illustrated “the black hand of the capital” and “the wild growth of the entertainment industry.” And in an editorial article, the state-run Global Times tabloid said the Alibaba scandal reflected a need for greater “legal and moral supervision” in the tech world, and for companies to better align their “capital” with societal values.

Notably absent from official rhetoric is any emphasis on what activists say are the roots of the problem: lack of support for survivors of gender-based violence and entrenched gender inequality in many aspects of society.

Part of the reason the government is so wary of acknowledging public outrage around these underlying issues is because it might encourage greater social organizing and activism, said Lv Pin, a prominent Chinese feminist now based in New York.

Neither of the alleged victims who stepped forward in both the Kris Wu and Alibaba cases alluded to #MeToo, which can easily draw censorship on social media, Feng said.

However, for many activists, the two cases still offer a ray of hope – and a sign that even if the government doesn’t want to talk about sexual misconduct, the public does.

“No matter whether they call it #MeToo or not, the essence is #MeToo,” said Feng. “Although most prominent feminist social media accounts have been censored, the victims can always manage to find their own ways to speak out.”