Leaders of the nonprofit Neighbor2Neighbor had high hopes for their Covid-19 Vax to School clinic in Randolph County, Georgia.

Their rural town about 170 miles south of Atlanta has not fully embraced Covid-19 vaccines, but the group’s clinics earlier in the year were popular. After the county schools temporarily closed due to Covid-19, they knew this one was needed.

So, the bright blue and green Phoebe Putney Health System mobile Covid-19 vaccine bus made the half-hour drive from Albany this month. Nurses in scrubs that matched the logo hustled in and out of a former school building, wheeling in plastic crates of vaccine supplies.

The vaccination target for this clinic was one of the most difficult to reach anywhere: teens.

The Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine is available for people 12 years and older, but teens remain the least vaccinated of any eligible age group in the United States. Only 46% of 12-to-17-year-olds in the US are fully vaccinated, according to a CNN analysis of data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. By contrast, 83% of adults over 65 are.

The teen vaccination rates in Randolph County, where the Vax to School event was held, is much lower. As of last week, only 10% of 12-to-14-year-olds in Randolph County had at least one dose. For 15-to-19-year-olds it was about 20%, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

One reason may be a misconception that has lingered from early in the pandemic, said Dr. Adam Ratner, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

“I think there’s still this leftover feeling that this is a pandemic of the elderly, which it is not any more,” said Ratner, who is also a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. “With the number of children we see infected and children with severe disease right now, Covid is a real problem, but people still believe this myth.”

Children are far less likely than adults to suffer serious disease or to die from Covid-19, but they can catch it, and September has been a bad month for kids. In the United States, more kids have caught Covid-19 in this month than any other in the pandemic, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

And they can die. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 571 children 17 and under have died from Covid-19.

It was a hard month in Randolph County, too.

For the last 30 days, the Covid-19 case rate is almost twice as high for 14-to-17-year-olds compared to adults, and three times higher than for people older than 65.

‘The kids need protection’

If anyone could reach people in Randolph County, it was Neighbor2Neighbor. Earlier in the year, the nonprofit saw success going door-to-door to answer people’s vaccine questions. At their vaccine clinic in July, a line of adults waited out the front door for much of the day. At least 80 people were vaccinated – a success for a county with 6,900 people.

The group hoped to see a similar line at their teen clinic. That Saturday, about a dozen volunteers spent the early morning turning a former lunchroom of the old J.B. Smith Schoolinto a clinic that could accommodate about 40 teens at a time.

Volunteers placed chairs the appropriate physical distance at round tables scattered throughout the room. Someone set out clip boards with permission slips near the front entrance. A half-dozen women buzzed around the kitchen assembling white to-go bags with chips and raisins for the vaccinated, and making room for the teen-friendly burgers and hotdogs the district’s school bus manager flipped on a smoker out back.

“It is crucial that everyone get vaccinated so we could beat this Covid pandemic,” said Sandra Willis, a volunteer with Neighbor2Neighbor who laid out masks and individual hand sanitizer on the giveaway table. Willis said her granddaughter, an eighth grader, is vaccinated, but several classmates were not, and some got sick.

The Randolph County schools shut down for several days in August. An elementary student and four high schoolers had confirmed Covid-19, according to a letter the district sent parents. The district decided it was in the best interest of its more than 800 students to take the time to disinfect buildings and buses.

The letter asked parents to “limit your interactions to a small circle of friends and family,” in addition to other pandemic precautions. The letter did not encourage vaccination, although the district’s Facebook page has advertised additional student vaccine clinics, as well as free Covid-19 testing and mask distribution events.

Since school reopened, there have been temperature checks before kids get on the bus and regular testing. Angela Wilborn, the county’s school nurse, helped set up for the Vax to School clinic, said said cases seemed to be better controlled, at least for now.

Masks and face shields are mandatory at school and seemed to be helping, Wilborn said. Students are good about wearing them, she said, especially after a recent graduate died from Covid-19 – an all-too-real reminder that this disease should be taken seriously.

Wilborn said she was optimistic about Saturday’s event.

“The kids need protection,” Wilborn said.

The first teen to get a shot

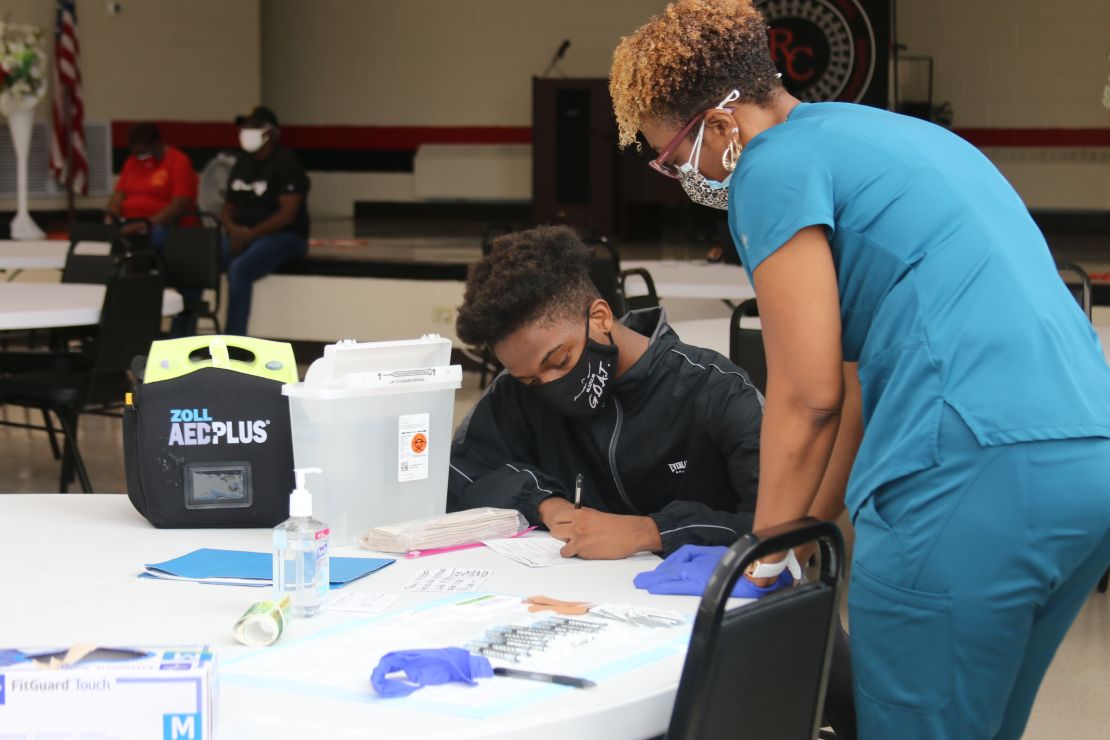

By about 9:30 a.m. a nurse from Phoebe Putney’s mobile clinic, Rhonda Jones Johnson, had carefully laid out 11 Pfizer shots. She put a box of latex gloves, hand sanitizer, a pile of Band-Aids, alcohol pads and bright green “Vaccinated, Combat Covid” stickers within reach.

A notecard filled out in Sharpie sat on the table to remind her what dates to tell patients when to get their second shot.

Another worker from the mobile clinic checked the numbers on the Pfizer vial and pre-filled out at least half a dozen CDC vaccination cards.

When the clinic officially opened at 10 a.m., the volunteers grew quieter. A few started to glance at the double doors. There was no line.

The clock at the back of the room ticked. Two volunteers sitting on a small stage chatted about the local mayoral election. A woman adjusted the clipboards. At 10:15 a.m., still no line.

“We didn’t go door to door to sign them up this time, but we advertised and handed out flyers at the shopping center,” Bobby Jenkins Jr., one of the leaders of the Neighbor2Neighbor program, said while watching the door. “We had a couple of people say they were coming, but you know how that is.”

Volunteers looked at their phones, speculated about when they’d get booster shots, and watched the rain out the bank of windows.

Finally, at 10:25 a.m. the double doors opened. The volunteers quickly stopped chatting.

“Hello,” the school nurse said in a friendly voice as a teen in a black track suit, Nike slides over his white socks, walked toward clipboards. His black face mask said G.O.A.T. over his left cheek.

The boy was followed by his family, including his mom, dad and older sister.

“Here you go, sanitize your hands,” the school nurse said as they circled around and she she squirted Purell into open palms.

“Once you fill that out, you’ll go right to over there,” she pointed to the table with vaccines.

“How are you today?” the other nurse asked as the boy sat at her table looking nervous. “Is this your first injection?”

The boy nodded. She told him when he’d get his next one and he nodded. Everyone in the room was watching.

“Which arm would you like?” the nurse asked. He lifted up his right elbow. The nurse sanitized her hands and put on bright blue gloves with a loud elastic snap. She hummed while she cleaned a spot on his arm.

“Ready? Stick,” she said as she plunged the needle in and pushed the tiny plunger. While most people looked away, the boy looked down, taking it all in.

“OK,” she said. He looked relieved as she put on a Band-Aid and pulled down his sleeve.

“If you don’t be feeling right, let me or Miss Angela know,” she said as he walked to sit with his family.

And with that, Raymond Slaughter became the first teen to get the vaccine at the Vax to School event.

“It was weird at first. I was kind of scared,” Slaughter said as he waited during the 15-minute observation period. “But it didn’t hurt at all. It was kind of cool to watch.”

Slaughter’sdad had already gotten vaccinated at the Tyson plant where he worked, and he joined the nurse watching over the small group to confirm nobody had a bad reaction to the shot. He said it was important for everyone to get the vaccine. Raymond agreed – he shouldn’t be the only teen who was there.

He hadn’t been out much during the pandemic, he said, and he misses school the way it used to be, before masks and Covid tests.

“I think people should come get it, just to make everybody else safe,” the 15-year-old said. “Now I will feel a little bit better about going out in public.”

And with that, the waiting period was over and everyone was fine. They picked up their hamburgers, to-go snacks and bundles of hand sanitizer, and went on with their Saturday.

The only teen to get the shot

It was another 20 minutes before the door to the vaccine clinic opened again.

The crowd of volunteers looked up, hoping for a group of teens. Instead, in walked a man in his 70s, the curls at the back of his head gray with age. No grandkids or nieces or nephews.

Over the next couple hours, a trickle of adults came into the clinic.

The nurse reorganized her supplies. Some volunteers began to eat the hamburgers and hotdogs.

“I was hoping we’d get at least 25 people, or 50,” said Willis who was eating a box of raisins. “It’s just inexcusable.”

At about 1 p.m., with an hour left to go, Willis tried a last ditch effort to draw people in: Facebook Live.

“I’m here at J.B. Smith School,” Willis said holding her mobile phone up. A volunteer hid a bag of chips she was eating as the camera panned the room.

“Come on down and be safe. No one is here and we have done about 10 people so far and have room for a lot more,” she said to the camera as she spun the camera to show she was in a room empty of teens.

But by 2 p.m. when the clinic was supposed to end, there had been more volunteers than newly vaccinated.

Three unused Pfizer vaccines sat on the nurse’s table.

Raymond Slaughter, it turned out, was the only teen to get the vaccine at the teen vaccine clinic.

“I don’t know why people aren’t caring enough to get their young ones vaccinated,” Willis said later.

Dr. Claire Boogaard, the medical director of the Covid-19 Vaccine Program at the Children’s National in Washington, DC, said parents and even teens will make a Covid-19 vaccine a priority if they see the threat – but teens aren’t really built that way.

“Teens don’t see risk the same way adults do. Developmentally it’s not normal for them to think ahead to long-term consequences at this stage of adolescents,” Boogaard said

Boogaard said a teen’s pediatrician may be able to persuade them to get the vaccine and they may also be able address any hesitancy on the part of the parents.

Mandates would also work. California is currently considering a statewide Covid-19 vaccine mandate for all children 12 and older.

NYU’s Ratner thinks that’s coming.

“It’s clear we are going to be dealing with Covid-19 for quite a long time. I think a Covid vaccination is going to end up being a routine vaccine for children,” Ratner said. “I would certainly encourage schools to consider it just like we mandate a lot of different vaccines to go to school.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

But even without a mandate, Neighbor2Neighbor’s Willis hopes people will take Covid-19 seriously and get everyone who can vaccinated.

“Too many people are dying. It’s not just older people, but younger people who have not been vaccinated,” Willis said. The writing is on the wall. Why can’t they read it? They need to be vaccinated.”