Images captured by the Perseverance rover have allowed scientists to peer back in time at what Mars was like billions of years ago.

Jezero Crater, the rover’s exploration site on Mars, was a quiet lake 3.7 billion years ago. A small river fed into the lake, sometimes leading to flash flooding that was so energetic, it could carry large boulders from miles upstream and drop them into the lake. The massive rocks are still there today.

These findings, which were published Thursday in the journal Science, come from the first scientific analysis of rover images that show outcrops of rocks inside the crater.

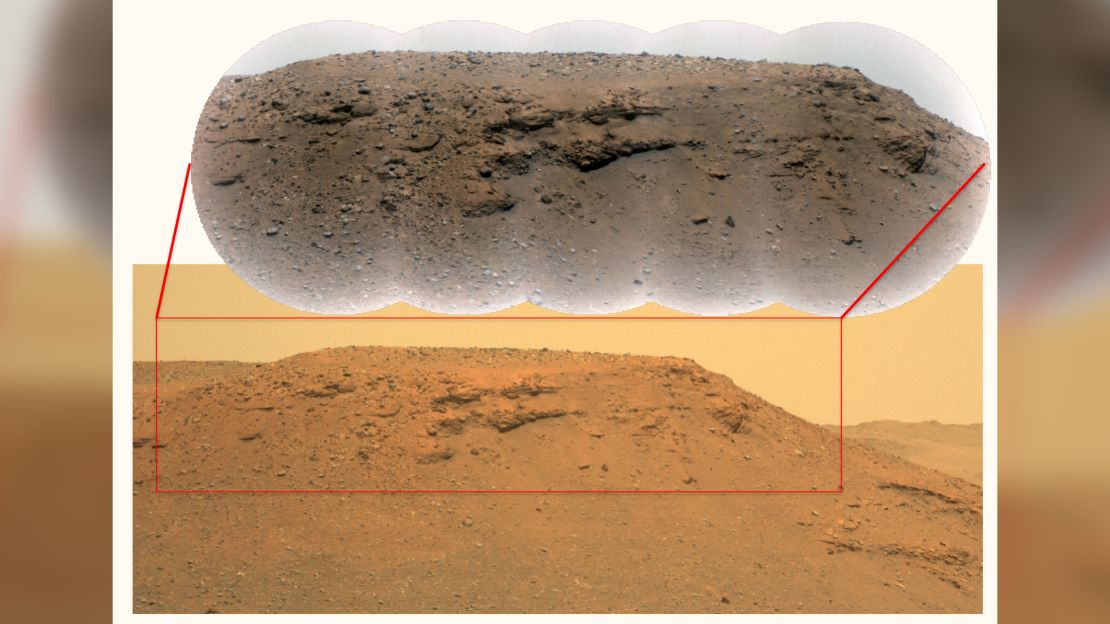

The new information shows the importance of sending rovers to explore the surface of Mars. Previous images captured by orbiters had shown that this outcrop resembled the kind of fan-shaped river deltas we have on Earth. Perseverance’s images show definitive proof of the river delta’s existence.

“It helps us understand so much more about the water cycle on Mars,” said Amy Williams, study coauthor and University of Florida astrobiologist, in a statement. “From orbital images, we knew it had to be water that formed the delta, but having these images is like reading a book instead of just looking at the cover. This is the closest I will ever get to going to Mars and doing this work in person. Seeing these rocks as I would in real life, looking up at them, is really staggering and really beautiful.”

When Perseverance landed at Jezero Crater on February 18, it was just over a mile away from the delta. Before the rover’s wheels ever started rolling, it immediately began taking pictures and sending them back to Perseverance’s science team on Earth – like Martian postcards with high scientific value.

The images showed tilted layers of sediment that were likely created by flowing water, rather than flat, even layers that would have been due to wind or other processes.

The top layers of the delta outcrop include large boulders, some as wide as 3.2 feet (1 meter) across that likely weighed several tons. Given their location on the top layer of sediment, they had to have originated from outside the crater. The scientists believe they originated from bedrock on the crater rim – otherwise, they came from 40 or more miles upstream of the lake.

But flash flooding, flowing at a rate as high as 29.5 feet (9 meters) per second, could have carried them down.

“You need energetic flood conditions to carry rocks that big and heavy,” said Benjamin Weiss, study author and professor of planetary sciences in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in a statement. “It’s a special thing that may be indicative of a fundamental change in the local hydrology or perhaps the regional climate on Mars.”

The fact that the large boulders sit on fine layers of tilted sediment also illustrates that the lake was largely calm until it was hit with flash flooding events before drying up. Then, billions of years of wind eroded away at the dry lake bed and delta.

“The most surprising thing that’s come out of these images is the potential opportunity to catch the time when this crater transitioned from an Earth-like habitable environment, to this desolate landscape wasteland we see now,” Weiss said. “These boulder beds may be records of this transition, and we haven’t seen this in other places on Mars.”

While the cause of this shift in climate remains unknown, the rocks could tell the tale – part of a larger story about why the Martian climate changed from warm and wet to cold and dry.

“If you look at these images, you’re basically staring at this epic desert landscape. It’s the most forlorn place you could ever visit,” Weiss said. “There’s not a drop of water anywhere, and yet, here we have evidence of a very different past. Something very profound happened in the planet’s history.”

A key part of Perseverance’s mission is not only to explore the crater and river delta, but collect samples from intriguing rocks across both. Future missions will return more than 30 of these samples to Earth by the 2030s. The samples could reveal whether life ever existed on ancient Mars – and these new images can help scientists determine the best rocks to sample as they search for evidence of ancient microbe fossils.

“We now have the opportunity to look for fossils,” said Tanja Bosak, study coauthor and professor of geobiology at MIT, in a statement. “It will take some time to get to the rocks that we really hope to sample for signs of life. So, it’s a marathon, with a lot of potential.”