Sign up for CNN’s Stress, But Less newsletter. Our six-part guide will inform and inspire you to reduce stress while learning how to harness it.

During school shutdowns, educators did their best to re-create in-class learning online. But what about the kind of learning that happens in the hallways in-between classes, or on the playground during lunch and after school?

Those in-person social interactions, the sort that emotionally challenge, enlighten and torment our children, were not transferable to video conference calls.

Now the kids are back, in the presence of the peers they click with, peers they forgot about, and peers they weren’t particularly looking forward to seeing again. Late-childhood friendships are hard enough as it is, as the business of figuring out who we are in the context of others makes for a rather messy process. Add a year or more away from a physical campus, and social connection can be even trickier.

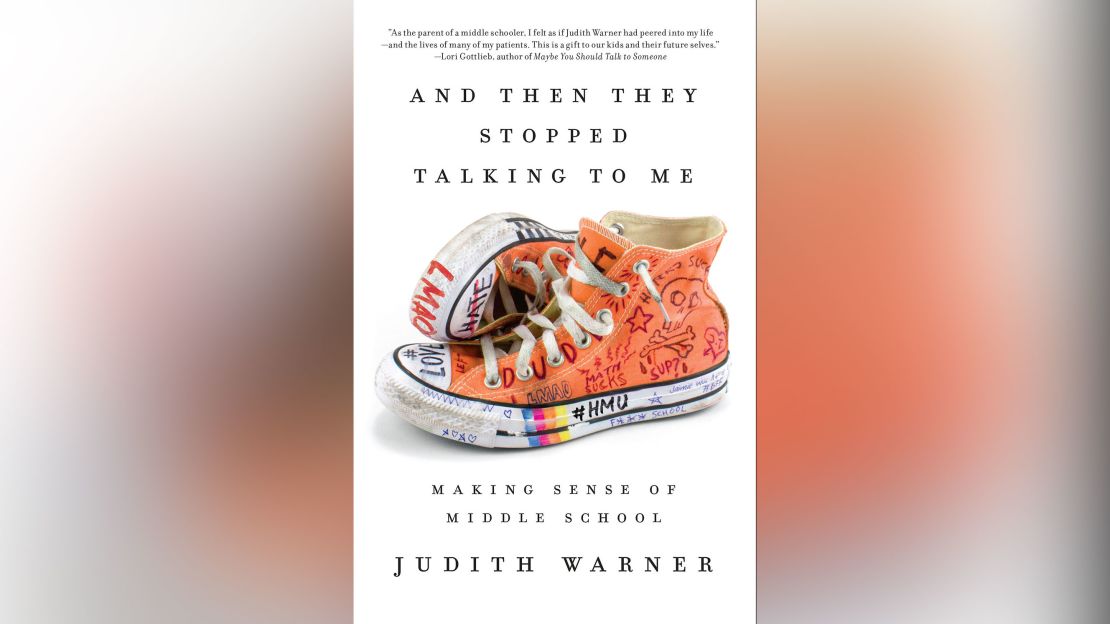

CNN spoke to Judith Warner, the author of “And Then They Stopped Talking To Me: Making Sense of Middle School,” about how to help make this transition as tearless as possible for kids. Warner explained the awkwardness of reacclimating to social life as an older child, the brain chemistry of this period, and how well-meaning adults may be complicating matters for their kids. While she focuses her book and research on middle school kids, the lessons and insights apply to all ages, including (sometimes) grown-ups.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

CNN: How could all that time off from in-person school be making life more complicated for some kids now that they are back?

Judith Warner: Kids are experiencing a combination of being thrilled to be out and seeing people and doing at least some of the same activities they loved doing beforehand, and going through a period of adjustment to being back.

Kids who are struggling to socialize or reacclimate may be experiencing sensory overload and are exhausted. On one hand, socialization is hardwired. But on the other hand, if you don’t socialize then the wiring doesn’t develop at the same speed. Social skills, like academic skills, get stronger through practice. After a year and half off, it makes sense that kids’ social skills are rusty. Mine are rusty, too.

CNN: Any benefits to that time away that adults should try to encourage or preserve?

Warner: During that long break, a lot of tweens and teens reconnected with friends they had moved on from – maybe because they weren’t in the same social circle or maybe because one was on their way to being “cool” and the other wasn’t. During the pandemic there wasn’t the social geography of the school day, with all its cliques and informal rules about who stands where during recess. That was disruptive in a sometimes-good way because it meant that kids felt freer to be in touch with whom they wanted to be in touch with.

CNN: What’s going on in the tween and teen brain that makes them particularly sensitive to the life interruption we all just experienced?

Warner: There are important parts of the brain that have a huge growth surge right around puberty. As a result, kids this age develop an incredibly sharp memory, and everything affects them more. They are also hardwired to crave approval and popularity from peers. But this is the teenager variety of approval and popularity, which is based on perceived power and appearance, as opposed to people actually liking you.

It’s kind of like a sick cosmic joke. You are suddenly more aware of how others see you right around the time that meanness and bullying spike.

But there is a good side to it, too. At this age, kids can have wonderful friendships, filled with joy, and discover all kinds of interests and follow them with passion. The world opens up to them, and it can be a good or bad thing.

CNN: How should adults speak to kids about any social awkwardness they might be experiencing right now?

Warner: To start, it’s important to follow their lead and not bring up something if the kids don’t and otherwise seem fine. I think we are all inclined to overidentify with our kids so if they are in pain, we are in pain. We also tend to hold on to it longer than they do and have it hang over us like a dark cloud, when they have moved on.

It’s also important to make sure kids know they have someone to go to and talk about hard social situations. It might be a parent, or someone at school like a teacher or a counselor who they trust and feel close to and who will give them objective feedback.

When your kids are home, sitting around the kitchen bashing someone, ask questions. Don’t just agree that so-and-so sounds like a b*tch, tempting as it may sometimes be. And don’t just tell them gossip is horrible, which inevitably fails. Instead, try to get actual information about why they are talking about this person that way.

Try to steer them in the direction of seeing things from this other kid’s point of view. Help them see him or her as a real person, because it is hard to fully write someone off when they become a real person with complicated feelings and contradictory emotions just like them. This doesn’t mean they have to like everyone, but they should be developing the sense that we should seek to protect the feelings of other human beings.

Anything you can do to lead them in the direction of basic kindness does a favor to both kids. Research shows that being competitive doesn’t make people happy, while being generous, kind and open-minded does.

CNN: You write about how our educational system and broader culture contributes to social stress of the tween and teen years. What are we getting wrong?

Warner: When I started working on the book, I had conversations with adults from France, Spain, India and elsewhere — and none of them had the negative associations with middle school that I had. They didn’t shutter or gasp or remember it as being the worst. I found research to back this up. Using a number of measures, middle school-age American kids scored as much less happy than their peers in other countries.

Some of that might have to do with the way our school systems separate them out. Kids can do better in K-8 schools, staying in that homey atmosphere of elementary school instead of starting something new during this vulnerable time. When kids feel vulnerable or weak, that makes them more likely to be mean. Some districts are already moving to this (school structure).

Also, the competitive nature of American life, which adults often transmit to their kids, isn’t helping. It erodes our sense of community, solidarity and kindness because, as psychologist Suniya Luthar explained to me, if everyone is competing for the brass ring, then everyone else is, by definition, their competitor. That does not create a happy or friendly world.

CNN: Might our collective experience of vulnerability and uncertainty during the pandemic help change that?

Warner: I hope we’ll see tweens and teens experience a version of something I’m noticing with adults: After so much time at home, doing Zoom calls without getting professionally dressed, kids and cats wandering in and out of the screen, I think people are permitting themselves to be a little more human in their professional conversations.

It’s as though presenting a perfect face, physically and verbally, has gone the way of dyeing gray hair. It would be fantastic if a similar sort of solidarity, based on an acknowledgment of our collective vulnerability, was built up among kids – and even better if it sticks around while life returns to something like normal.

Elissa Strauss is a regular contributor to CNN, where she writes about the politics and culture of parenthood.