On November 2, 2020, Jack Ma’s Ant Group was gearing up for the biggest initial public offering in history.

One day later, it all fell apart.

Beijing’s decision to yank the $37 billion IPO was just the start of a sweeping crackdown that has become one of the most consequential realignments of private enterprise in China’s history.

In the year that followed, the Chinese government’s regulatory might has changed industries ranging from tech and finance to gaming, entertainment and private education.

China’s regulators aren’t alone in moving to restrict what they see as overly powerful companies, especially in Big Tech. Authorities in the United States and Europe have also moved over the last year to rein in unruly playersby proposing new antitrust laws or trying to regulate data and online content.

But the speed and ferocity with which Chinese authorities have acted against the country’s corporate titans have startled even the closest China watchers.

“The latest regulatory tightening cycle is unprecedented in terms of duration, intensity, scope, and velocity,”analysts from Goldman Sachs wrote in a recent research report.

The campaign has wiped out more than $1 trillion worldwide from the market value of Chinesecompanies. It has sent chills through the wider economy and stoked fears about the prospects of future innovation and growth in China.

Some of China’s most successful entrepreneurs have quit high profile jobs in the past several months — decisions they’ve claimed are unrelated to the turmoil, but which analysts find hard to separate completely. Several tech firms have pledged to hand billions of dollars worth of their own profits to government-backed social causes. And some big proponents of Chinese investment havereconsidered plans to pour more money into the market until the outcome of the political interference is clear.

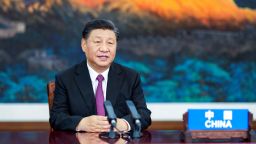

While China’s decisions have rocked the corporate world and rattled foreign investors, Xi appears undeterred. To him, reining in private enterprise is the solution to fixing longstanding concerns about consumer rights, data privacy, excess debt and economic inequality.

In other words, for the Chinese Communist Partyit’s not about killing the private sector: It’s about taming the excesses of capitalism and embracing the country’s history of socialism.

“Common prosperity is the prosperity of all the people, the material and spiritual life of the people being rich,” Xi wrote in an article published last month by a Communist Party journal, invoking a historically significant phrase that dates back to the time of Chairman Mao Zedong. “It is not the prosperity of a few people.”

Dividing the ‘cake’

China is one of the world’s most unequal major economies, according to the World Bank. Its Gini coefficient — a popular measure of inequality — has increased significantly over the past four decades, coinciding with the country’s staggering rate of economic growth.

That meteoricrise accelerated under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, who took power in the late 1970s after the death of Mao.

Under Deng, the country embraced the free market and opened up to global trade. He famously said in 1985 that “some people can get rich first” to help poorer people in the long run, so that the society can gradually achieve “common prosperity” — a use of the phrase that differed significantly from its invocation by Mao, who advocated for wealth redistribution nearly 70 years ago as he worked to cement the party’s control.

Worsening inequality now appears to be vexing Xi, the country’s most powerful leader in decades. Just last year, his government concluded a five-year long fight against absolute poverty. Now he’s widely expected to seek a third presidential term next year, and has focused his time on reducing the wealth gap.

“We must divide the cake well,” Xi wrote in last month’s article, adding that his goal is to “achieve common prosperity of all people by the middle of this century.”

A desire for control

Analysts widely believe that Xi’s concerns about inequality are real, but that the unfolding crackdown also signals the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s desire for control.

Xi is “aware that a Communist Party regime only enjoys legitimacy as long as common people feel represented,” said Sonja Opper, a professor at Bocconi Universityin Italywho studies China’s economy and the private sector. “The ultimate motivation is more likely to gain control over powerful parts of the economy.”

The business crackdown that dominated much of this year is believed to have started after Ma — easily the most recognizable of China’s business elite — blasted China’s financial system during a controversial speech in October 2020.

Ma criticized China’s regulatory system at the time as being outdated and risk averse, an obstacle to the high flying, innovative tech firms that he said could bring banking to poor populations and smaller businesses that are otherwise locked out of traditional finance.

The tech entrepreneur also accused China’s conventional, state-controlled banks of having a “pawn shop” mentality by lending only to borrowers who could provide collateral.He toutedmore innovative, data-heavy approaches ascapable of bringing banking to marginalized groups.

Those words likely spurred Beijing to retaliate swiftly. The Ant Group IPO was suspended just over a week later.

Since then, life has only gotten more difficult for Ma, Ant Group and China’s other corporate giants. The usually flamboyant Ma has all but disappeared from public life, and has even reportedly left the helm of an elite business school he founded.

Ant Group was forced to overhaul its business and become a financial holding company, meaning it is much more heavily regulated than it ever was before.Ma’s Alibaba (BABA), meanwhile, was hit earlier this year with a record $2.8 billion fine for behaving like a monopoly, and the company has lost roughly $400 billion in market value in the last year as it navigates a slew of new regulations from Beijing.

More than Jack Ma

Ma’s business empire isn’t the only one affected. Meituan, Tencent (TCEHY), Pinduoduo (PDD) and other tech firms have also been investigated or fined over alleged anti-competitive behavior. And the ride-hailing app Didi — which went public in the United States despite reported concerns from Chinese regulators — was banned from app stores and probed over questions about data security.

The Communist Party “seems increasingly concerned that China’s tech sector has become so globally prominent that it runs the danger of outrunning the Party itself,” said Rana Mitter, a professorwho specializes in the history and politics of modern China at the University of Oxford. “The crackdown helps to bring it down to size.”

The clampdown has extended well beyond tech. Rules published in July upended China’s $120 billion for-profit tutoring sector. Additional guidelines released that month tightened oversight of the country’s massive food delivery industry.

The real estate market, which was already being roiled by government efforts to curb excessive borrowing by developers, has also been under intense scrutiny this year. Authorities have announced more than 400 regulations on the sector this year as they try to cut down on property debt and bring home prices under control, according to statistics compiled by Centaline Property, a Hong Kong-based property agency.

The government has also turned its attention to cultural and societal issues that authorities have deemed “unhealthy” or “toxic,” including overwork, unruly celebrity behavior and excessive time spent with video games. Other areas of pop culture have been scrutinized as well.

Wary of private tech’s power

Experts point to the crackdown — and especially the measures directed at technology — as the start of a new era for regulation in China.

Companies like Ant Group and Didi have rapidly ascended in recent years to become powerhouses in their fields. Alipay, operated by Ant Group, dominates China’s mobile payment market with a 56% share. Didi has a near monopoly of the ride-hailing market, with about a 90% share.

Beijing encouraged their rise at first. Such firms have been huge job creators and have attracted vast amounts of foreign and domestic capital. China’s influence as a hub for technological innovation has also exploded in recent years because of these firms, which compete head to head with Western rivals.

But now the government is growing wary of their size and power.

Firms like Alibaba, Tencent and Didi “will no longer be able to stay under the protective umbrella of Internet or technology, outside of supervision from the Chinese government,” said Doug Guthrie, a professor and director of China Initiatives at Arizona State University’s Thunderbird School of Global Management.

Beijing is also clearly concerned about the collection of data by these private firms. The technology they have created is so prevalent in Chinese life that they have access to sensitive information about hundreds of millions ofpeople, ranging from where and when they travelto specific details about how they spend their money.

“It cannot go unnoticed that the industries and sectors that came under fire are all part of the modern tech economy, controlling vast amounts of individual level data,” said Opper from Bocconi University. She added that data “is an invaluable resource for any government wishing to control all walks of life.”

Beijing’s interest in Big Data was apparent this summer, as the government’s probe of Didi and other Chinese companies that trade in the United States took shape. Authoritiesfocused on allegations that those firms mishandled sensitive data about their users in China, posing risks to personal privacy and national cybersecurity.

Those regulations “may therefore simply reflect the desire to gain control over the type of data and technology that is currently controlled by China’s most innovative, private technology corporations,” Opper said.

Economic slump may bring change of pace

Beijing has signaled the crackdown may not be over yet.

In August, the party’s top leaders unveiled a major policy blueprint for the next five years, in which they pledged to strengthen regulations on tech, financial services, education, and tutoring firms — areas of what they called “vital interest.”

But other factors might force the government to slow the pace and scale at which it is trying to transform private enterprise.

The world’s second largest economy has encountered a slew of challenges that are weighing heavily on economic growth, including disruptions due to the global shipping crisis, a massive energy crunch and concerns about a debt crisis in real estate. Last quarter marked the slowest pace of GDP growth in a year.

The crackdown on tech and education firms hasn’t helped, with demands for rapid change resulting in job losses and a drag on retail sales.

“My prediction: The ‘crackdown’ is going to stop now,” Guthrie said.

“The Xi administration is very committed to economic growth,” he added. “They have made their point about the coordination between the government and the private sector. But they know they need an entrepreneurial private sector to continue to drive China’s growth.”

There has been some indication that the regulatory push is slowing down.

Guo Shuqing, chairman ofthe China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, told state broadcaster CCTV last month that thenew regulations forfinancial tech firms have“yielded initial results.” He said he expects to achieve “even more significant progress” before the end of the year.

Even Ma is reportedly turning up in publicagain. Reuters reported last month that the tech billionaire was spotted on a cruise in Spain,his first trip outside China since the crackdown began.

The government wants companies to understand that they need to be in “lock step” with authorities, said Guthrie, who added that “no one gets to think of themselves as bigger or more global than the Chinese government.”

But he acknowledged that Beijing knows it needs Chinese tech to flourish.

“My sense is that the support and coordination between the government and the private sector is coming back into alignment,” he added.