Editor’s Note: Andrei Kolesnikov is a senior fellow at Carnegie Moscow Center, and the author of several books on the political and social history of Russia, including a biography of the Russian reformer Yegor Gaidar. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. Read more opinion articles on CNN.

When the Soviet Union finally fell, it was in a mundane way, as if it had clocked off from a normal day’s work.

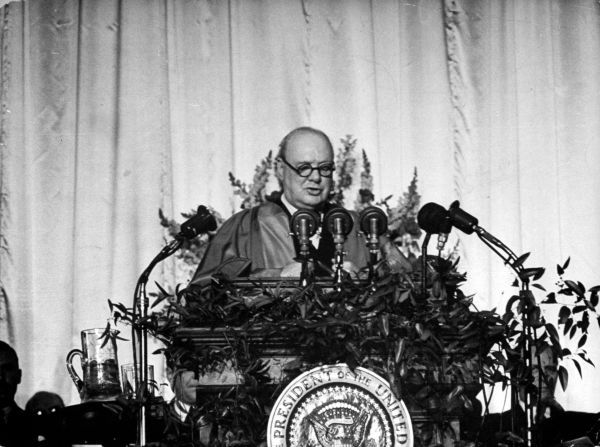

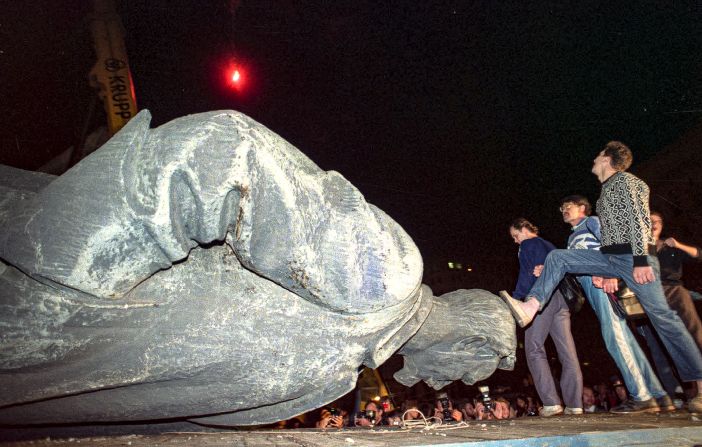

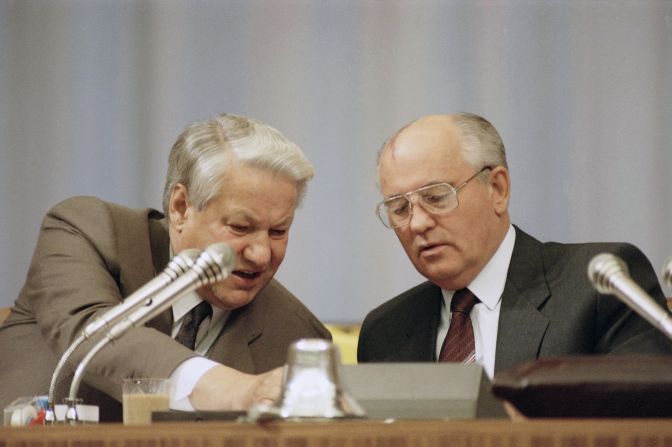

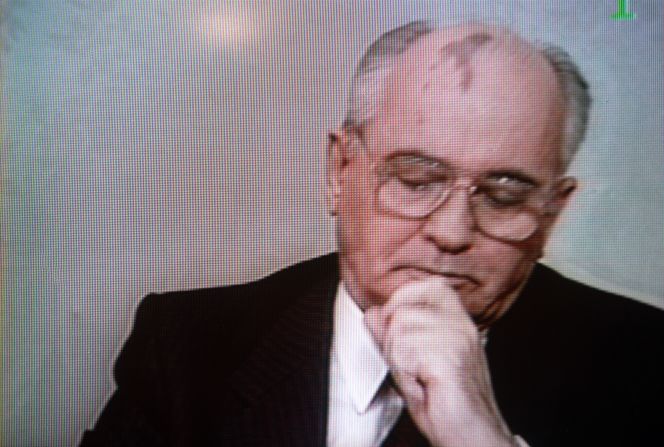

On December 25, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev addressed the Soviet citizens and announced his resignation as president. A little after 7:30 p.m. that same day, the Soviet flag, waving in the wind, was lowered from the flagpole above the presidential residence in the Kremlin.

For five minutes the flagpole stood bare, as if to symbolize the transition of power. By 7:45 p.m. the Russian tricolor was hoisted on it.

The following day, the Soviet Union was officially dissolved. And with that, the empire in which I’d been born and spent the first 26 years of my life came to an end. The backdrop for my family’s story – which included losses during World War II and Stalin’s repressive dictatorship – had come down.

But I must admit that when that flagpole stood naked, I felt nothing.

For me, the Soviet Union became a thing of the past after the attempted coup of August 1991. Gorbachev pulled strings, believing he was running the country, but the strings were cut. Ministers and regional leaders wrote alarmist letters to one another – food supplies were thinning and the country was facing starvation. Russia was creating a reform government.

As a budding journalist, I was enthusiastic about the change. I worked at a newspaper, eagerly reporting every day what the reformers were doing. My older brother meanwhile became an adviser to the chief reformer and later Prime Minister, Yegor Gaidar.

But amid the difficulties of the transition, peoples’ inspiration started fading over the following years and the bulk of the population discovered that capitalism did not bring immediate happiness.

Despite that, in the spring of 1993, people voted in a referendum to continue reforms, and in the autumn of that year the reformist party Vybor Rossii managed to form one of the largest factions in the new parliament. It was the last time when liberals were successful.

In 1994, less than three years after the Soviet Union collapsed, sociologists led by Yuri Levada recorded a change in attitudes. People began to say that they preferred quiet work for hire rather than their own businesses and the risks associated with them.

As more time passed, a substantial number of Russians began to feel pangs of nostalgia – Soviet songs were sung in New Year’s programs on television, post-modern Soviet-like menus became popular in restaurants.

But no one seriously thought of going back until 2000 when the new President – Vladimir Putin – quite literally changed their tune. Putin restored a revived version of the Soviet anthem, still used today.

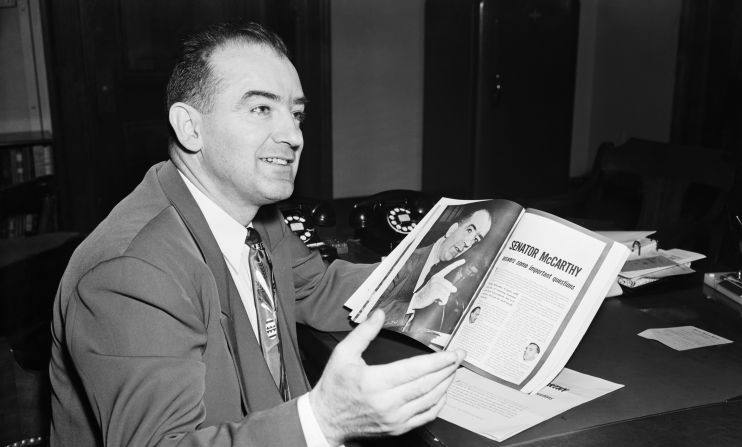

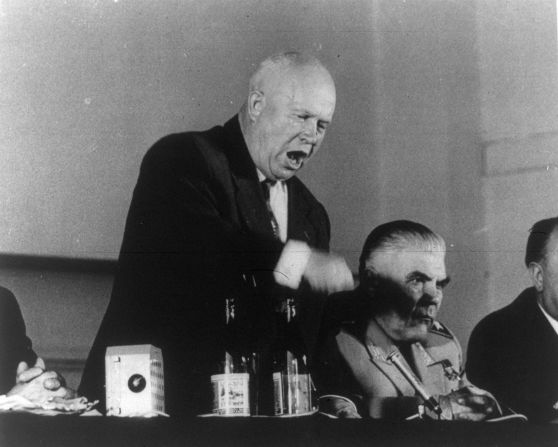

The President’s resurrection of Soviet ghosts didn’t stop there. Putin famously called the breakup of the Union the “greatest political catastrophe” of the 20th century, during an address in 2005. Two years later, he gave another speech in Munich about the humiliation of Russia by the West.

And it sounded like a plan: to “Make Russia Great Again.”

The domestic audience at the time didn’t take it too seriously – the average citizen wasn’t thinking about politics then, enjoying the recovery of economic growth and the high oil economy of the 2000s.

Putin’s popularity gradually declined and Russia’s modernization seemed inevitable. Though the short war with Georgia in 2008 did give his approval ratings a temporary boost.

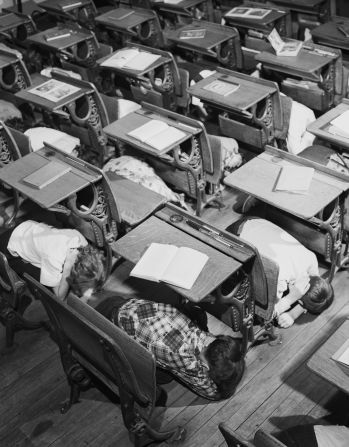

In 2012, Putin faced unprecedented protests by the urban classes, and began a very sharp U-turn towards ultra-conservative policies. And one of the main components of his propaganda was the glorification of Russia’s so-called victorious Soviet history.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 was portrayed as an act of “restoring the empire.” Imperial feelings were slumbering in the hearts of most Russians, and Putin played on this, reviving their pride in being part of a great power. As the Crimean effect wore off, Putin stepped on the pedal for Soviet nostalgia, presenting the Stalin era – particularly the Great Patriotic War – as one of victory and order.

Fast forward to 2021, and almost half (49%) of Russian respondents would prefer the Soviet political system, according to a study published in September by the independent Levada Center. The survey, which included 1,603 adult respondents across 50 regions of Russia, said it was a record figure of Soviet support for this century.

Surprisingly, there are no contrasting attitudes to the Soviet era across generations, our research from the Carnegie Moscow Center and Levada has found. The older cohorts are nostalgic for the USSR; the younger ones have developed an image of the Soviet Union as a fairytale country, a retro-utopia where everyone is equal, everyone is free, and a stern-but-just father figure rules.

People are dreaming of a fairer society, and Russians have no other models than the Soviet Union. The imaginary USSR still helps Putin in many ways – even when his regime is losing popularity to the Soviet system.

At the last traditional December hockey tournament in Moscow, the Russian team took to the ice wearing a Soviet team uniform, and the audience often waved the Soviet flag. Three decades after the Soviet flag was officially lowered, it still looms large in Russian life.