A year that began with a chaotic attack on democracy in Washington, DC – the “insurrection” at the US Capitol – ended with a more dignified defense of it, President Joe Biden’s “Summit for Democracy.”

The two events were suitable bookends for a year filled with turmoil and polarization – and not just in the United States.

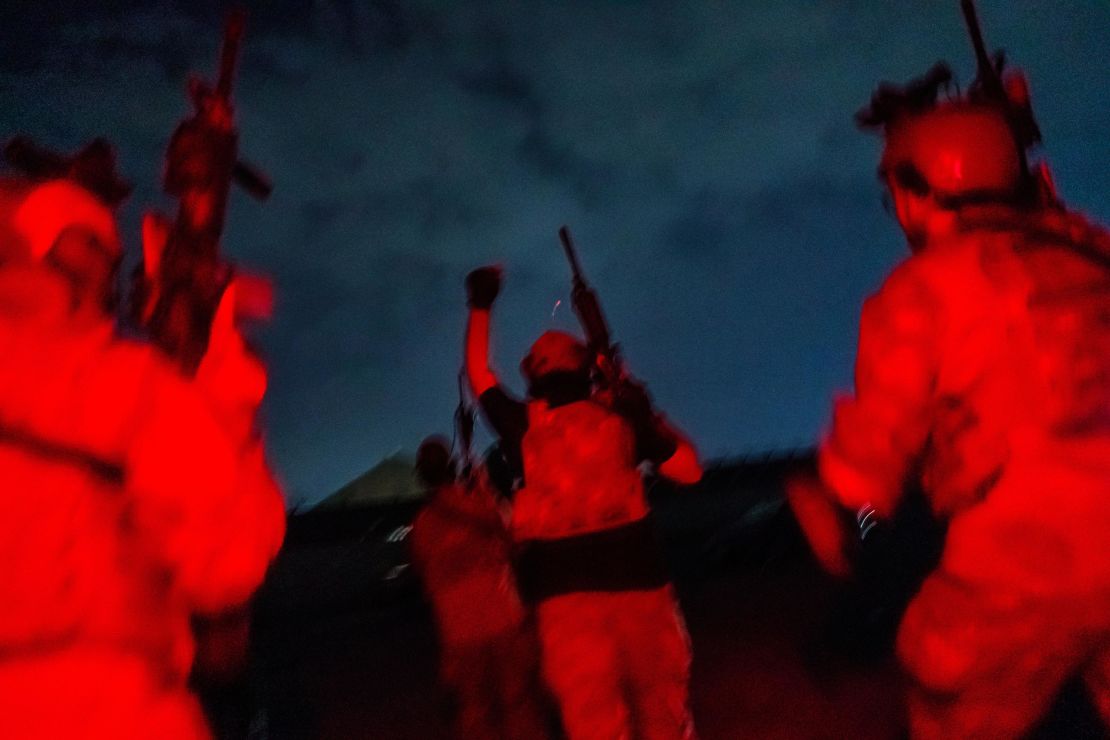

In between them came the humiliating and chaotic end of America’s democratic experiment in Afghanistan.

In 1947, Winston Churchill famously noted: “It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried.” In 2021, its example as the model to which nations should aspire was buffeted and beaten.

The last 12 months were also the year of vaccines, as the world hoped to escape the coronavirus pandemic. It didn’t.

Millions more died as a new variant, Delta, swept the globe, and vaccination itself became the cause of animosity, setting the vaccinated and the unvaccinated against one another, and highlighting both the inequity between rich and poor nations and the coercive power of government.

It was also the year of grand declarations but less impressive action on climate. Fires and floods from California to Siberia put humanity on notice – but the response at the COP26 summit in Glasgow was lukewarm.

And 2021 was the year when the full and far-reaching impact of social media, its misappropriation and how or whether it could be tamed, was viscerally felt.

Above all, 2021 seems to have been a year of warnings – about our relationships with technology, the planet and those who govern us, whether elected or self-appointed.

Democracy falters

The invasion of the US Capitol on January 6, fed by conspiracy theories about a stolen election and incited by a sitting President, was beamed to a shocked world.

The democratic process held and the result of the 2020 election was certified. But the rejection of an indisputable result by a furious minority, mutterings about martial law and the deployment of 20,000 National Guard members for Biden’s inauguration were an unprecedented shock to the system.

The events of that day were emblematic of toxic divisions in the United States.

Even before the election, Biden – as the Democrats’ presidential candidate – had warned: “Trust in democratic institutions is down. Fear of the Other is up. And the international system that the United States so carefully constructed is coming apart at the seams.”

In an effort to restore that trust and challenge a surge in authoritarianism worldwide, the Biden administration brought more than 100 countries together (albeit virtually) in early December for the Summit for Democracy.

China and Russia were conspicuously not invited. Biden had told a news conference in March that Chinese President Xi Jinping “is one of the guys, like [Russian President Vladimir] Putin, who thinks that autocracy is the wave of the future, [and] democracy can’t function in an ever-complex world.”

The Chinese Foreign Ministry reacted furiously to the summit, saying the US “sought to thwart democracy under the pretext of democracy, incite division and confrontation, and divert attention from its internal problems.”

Whether the event has the impact Biden intended will have to wait until 2022.

But if the events of January 6 were a low-water mark for democratic institutions, the 12 months since have not offered much comfort.

In many countries, especially those where democracy’s roots were shallow to begin with, freedoms have been eroded or vanished altogether. There were coups in Myanmar, Sudan and Mali, the unraveling of Ethiopia, rigged elections in Nicaragua. And above all the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan.

The collapse of Afghanistan’s US-backed government was a blow to Washington’s credibility, raising questions about how reliable it was as a partner and protector.

One month shy of the 20th anniversary of the September 11, 2001 attacks, it was also a shattering rebuke to America’s evangelizing mission for democracy and its technological superiority. The Taliban – allies of the group that brought down the Twin Towers – walked into Kabul without firing a shot. Tentative democratic advances – especially on women’s rights and media freedoms – were stifled overnight.

For the 15th consecutive year, the US non-profit Freedom House reported a decline in democracy worldwide, “with authoritarians generally enjoying impunity for their abuses and seizing new opportunities to consolidate power or crush dissent.”

It said that in India, the nationalist government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi had “presided over discriminatory policies and increased violence affecting the Muslim population,” and that harassment of journalists and NGOs had increased.

In response, India’s government said it “treats all its citizens with equality as enshrined under the Constitution of the country and all laws are applied without discrimination.”

The Stockholm-based Institute for Democracy and International Assistance said President Jair Bolsonaro “has openly tested Brazil’s democratic institutions, accusing magistrates of the Superior Electoral Court of preparing to conduct fraudulent activities with regard to the 2022 elections and attacking the media.”

The European Union has been roiled by challenges to free media and an independent judiciary in Hungary and Poland. Viktor Orban’s government in Hungary was notably not invited to take part in Biden’s summit.

The last vestiges of dissent in Russia were snuffed out, with opposition politician Alexei Navalny sent to a penal colony when he dared to return home. Putin’s appetite for coercion was on full show with a troop build-up near Ukraine, complemented by a sophisticated disinformation campaign that questioned Ukraine’s very right to exist.

The most profound challenge to democratic values came from an ever-more assertive China, where Xi’s steely grip tightened.

The year 2021 saw the expansion of sophisticated disinformation campaigns to cover up human rights abuses in Xinjiang and even aggravate dissent in the US about the pandemic.

China, which denies rights abuses in Xinjiang, also intensified its ideological attacks on the West – advancing a new sort of international order as trust in democracy faltered.

As China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi put it: “The practice of democracy varies according to different national conditions and cannot be one template or one standard.”

But Beijing’s challenge was far more than ideological. Belligerence toward Taiwan grew, and it accelerated development of hypersonic missiles, a program described by Gen. John Hyten, the former vice chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, as “stunning.”

“The pace they’re moving and the trajectory they’re on will surpass Russia and the United States if we don’t do something to change it,” Hyten said.

China maintains it is testing space vehicles, not missiles.

The Financial Times’ chief US commentator Edward Luce concluded: “Both Beijing and Moscow see America’s exhaustion as a chance to settle unfinished business – in the South China Sea and in former Soviet territory.”

But, he added: “They may be dangerously misjudging America’s capacity to change its mood.”

Doubts and discontent

As autocratic regimes went on the front foot, a mood of uncertainty and unease pervaded many Western countries. Survey after survey identified growing public discontent, frustration about corruption and inequality and the handling of the pandemic.

A Pew Research survey of 17 countriesfound that in Italy, Spain, the United States, South Korea, Greece, France, Belgium and Japan, about two-thirds of people “believe their political system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed.”

But a majority of respondents have little or no confidence that those changes will happen.

Discontent extends to the liberal economics that have driven global growth for three generations. In Italy, Spain and Greece, at least eight in 10 believe the economic system needs major changes or a complete overhaul. Two thirds in the US and France share this sentiment, despite robust recoveries in many Western economies as Covid-19 lockdowns eased.

There is close correlation between this discontent and views about the way coronavirus has been handled. In a survey of 13 advanced economies, Pew found 34% of people felt their countries to be more united during the pandemic, but 60% thought national divisions had worsened since the outbreak began.

Even as the world began to emerge tentatively from the pandemic, it remained vulnerable to its divisive consequences – over vaccine access inequity, mandates and lockdowns. The tussle between the social good and an individual’s rights was unforgiving.

To Saad Omer, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, “if you have the most libertarian perspective on life, vaccines and infectious diseases can be, and should be, and must be an exception.”

But others see vaccine mandates as an attack on their individual freedom. Even the UK Health Secretary, Sajid Javid, described them as “unethical.”

Vaccine hesitancy became one of the year’s catchphrases, especially in Germany, where deaths due to Covid-19 in December were at their highest since February, and the US.

And the debate became angrier.

Protests against mandates and compulsory health passes drew tens of thousands of people in France and Italy. On a cold weekend in December, more than 40,000 people protested in Austria against lockdowns and a vaccine mandate. Protests in Germany and the Netherlands turned violent.

In the US, workers risked being fired as they rejected what they saw as illegal and immoral attacks on their rights. There were even assaults on vaccination centers.

First world problems, perhaps. In much of the world, health workers fighting the pandemic didn’t even have the chance of vaccination.

Booster shots are being offered by the tens of millions in the US and Europe. But only 2.5% of the 6.4 billion vaccine doses administered globally have been in given in Africa, where 17% of the world’s population lives.

In 2020, the World Health Organization warned repeatedly of the risks and injustice of vaccine inequity. In 2021, that became reality.

So too did the pandemic within the pandemic – the stunning rise of mental health issues, especially among teenagers. Emergency room visits for suicide attempts rose 51% among American adolescent girls in early 2021, compared to the same period in 2019, according to the US Surgeon General. Save The Children found similar results in Spain.

‘Blah, blah, blah’

A very different strand of opinion has lost faith with the politicians over climate change. Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg captured that frustration during November’s COP26 summit in Glasgow. “Build back better. Blah, blah, blah. Green economy. Blah blah blah. Net zero by 2050. Blah, blah, blah,” she said. “Our hopes and ambitions drown in their empty promises.”

The long-anticipated summit staggered across the line, after agreeing that coal – the most polluting fuel – would be phased “down” rather than phased “out.” Despite high-sounding speeches, the final accord left the goal of restricting the increase in temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius on life support.

Meanwhile, in the world outside the COP26 conference hall, economies were trying to overcome supply chain disruptions amid a post-pandemic hunger for energy. In the face of rocketing oil and gas prices, the Biden administration asked OPEC to open the spigots.In the third quarter of 2021 alone, Exxon Mobil and Chevron made $12.9 billion in profits. Saudi Aramco made $30.4 billion in the same period.

Those price increases stoked levels of inflation not seen in the West for a generation and also left Europe even more reliant for its liquid natural gas on Russia.

The idea of “building back better,” a slogan embraced by both the UK and the US governments, has suddenly come face-to-face with short-term realities that threaten to turn it a very pale green. After dipping in the first year of the pandemic, oil consumption is back to where it was in 2019.

Babies, barbeques and bar mitzvahs

The debate about the global influence of social media, and how to regulate it, was ramped up thanks to an American named Frances Haugen, a former Facebook employee who leaked thousands of company documents. And it was given further impetus by a Nobel Prize winner (and former CNN reporter), Maria Ressa.

Haugen told a Senate committee she believed the company’s products “harm children, stoke division, and weaken our democracy” and it had put “astronomical profits before people.”

Accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, Ressa spoke of “the toxic sludge that’s coursing through our information ecosystem, prioritized by American internet companies that make more money by spreading that hate and triggering the worst in us.”

Many Americans appear to agree. A CNN poll found that 76% of Americans believed Facebook makes society worse, not better. The company insisted its platforms do not push incendiary content. Nick Clegg, its vice president of global affairs, said the vast majority of content on Facebook is “babies, barbeques and bar mitzvahs.”

But beyond the marketing and the algorithms of social media platforms, 2021 witnessed the continuing use of social media for incitement.

Facebook’s internal documents showed it was unprepared to deal with the “Stop the Steal” movement that led to the events of January 6. One of those documents captured the dilemma: “It was very difficult to know whether what we were seeing was a coordinated effort to delegitimize the election, or whether it was protected free expression by users who were afraid and confused and deserved our empathy.”

Such is the reach of social media – Facebook alone has 3.9 billion users – that the first efforts at regulating Big Tech in Europe and the US have only now come to the fore.

In the US, legislation has been floated that would end platforms’ immunity from prosecution where they “knowingly or recklessly” promote harmful content.

Which leaves us…

2021 has set the stage for struggles that will persist into the New Year and far beyond.

The US’ polarization was not cauterized by President Donald Trump’s departure. Instead, it has rumbled on, showing “how easily shameless partisans can undermine public trust in long-standing institutions,” according to Yasha Mounk in Foreign Affairs.

Democracies will have to compete with their adversaries in the marketplace of ideas, while attempting to cooperate on issues such as climate change, terrorism, cyber-security and health (ahead of the next pandemic).

And we will be trying to put coronavirus behind us while grappling with its economic, social and psychological aftermath.

Don’t expect 2022 to be an oasis of calm.