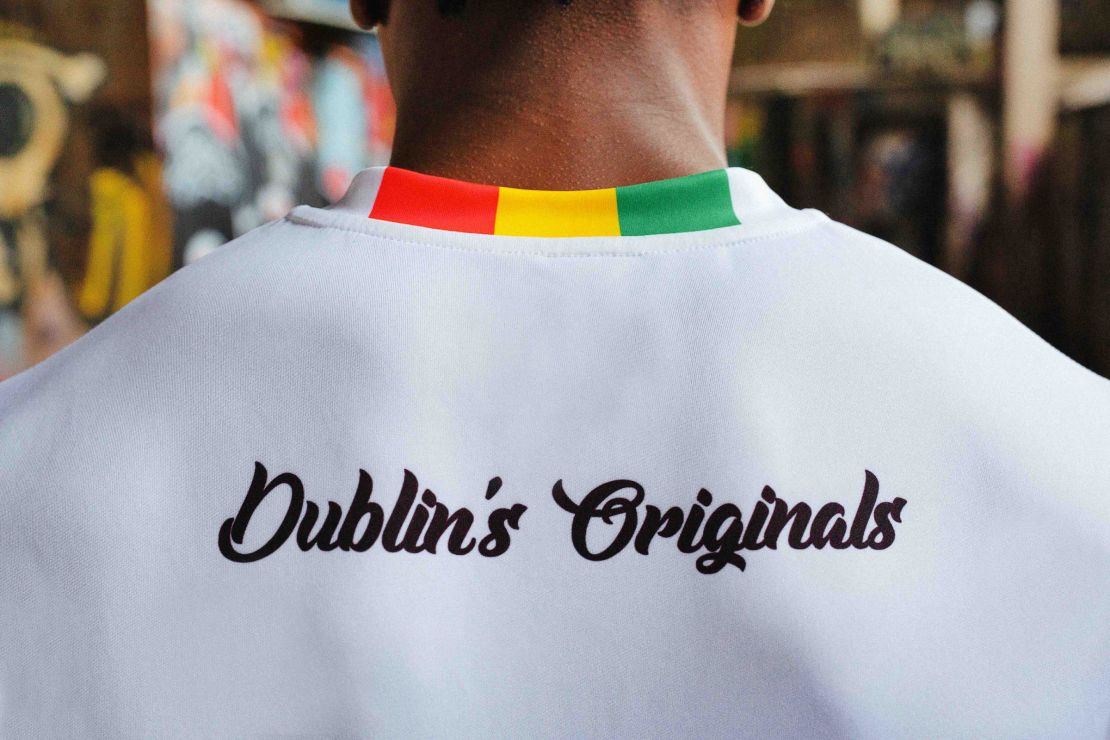

What is the next move for a football team that has a designated poet in residence and the sport’s very first climate officer? To design a shirt in honor of reggae legend Bob Marley, of course.

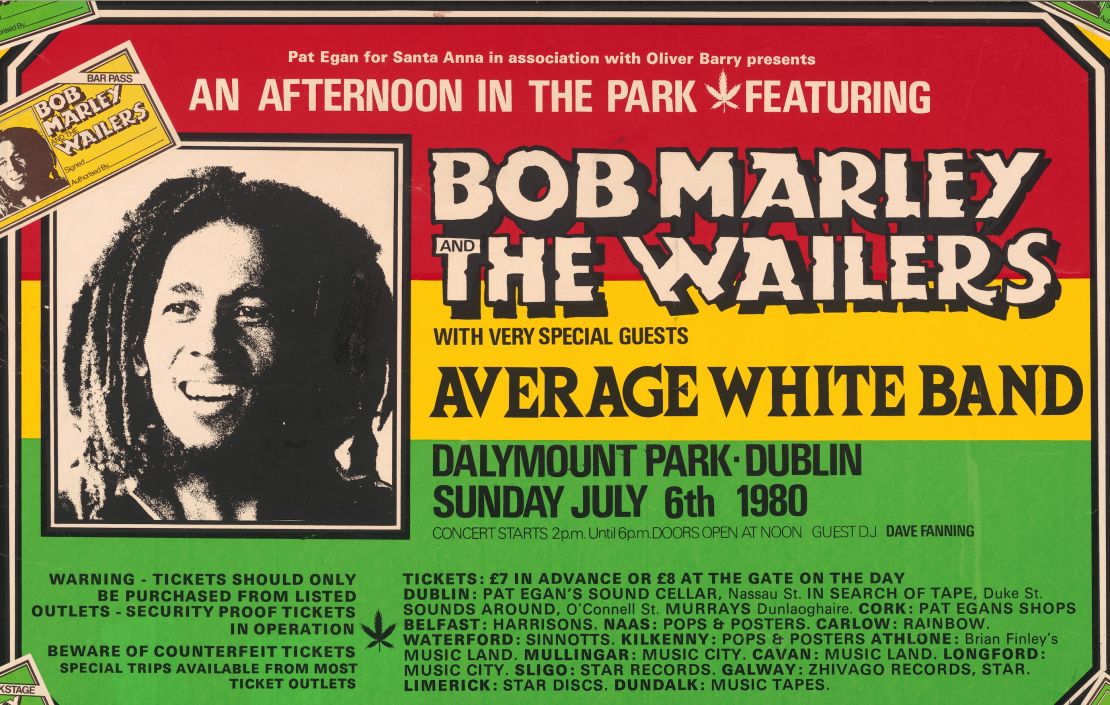

In the latest progressive scheme from Irish club Bohemians, a member-owned and not-for-profit team, the club have released a special away jersey to commemorate the Rastafarian icon’s last ever outdoor concert, which took place in the club’s stadium, Dalymount Park, on July 6, 1980.

And 10% of all profits from the shirt will be used to buy sporting and musical equipment for people in Asylum Centres in partnership with the Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland

The concept came from the mind of the club’s Chief Operating Officer Dan Lambert, who in part wanted to pay tribute to the club’s history – a timeline that, as Dublin’s oldest club, stretches all the way back to 1890.

“We’re always trying to use the natural assets of the club and one of the best assets we have is Dalymount and Dalymount’s history,” Lambert told CNN Sport.

“We’ve played in the ground since 1901 … Zidane and Pele and Van Basten and Ruud Guulit and George Best and Bobby Charlton, they all played there.”

But it was the ground’s storied history of music and in particular, the legendary Marley gig from 1980, that Lambert said was something that captured the imagination of the club’s local community in Phibsboro on Dublin’s northside.

“We have lots of gigs at the ground and music history. Particularly in the ’70s and ‘80s. We had Thin Lizzy and Meatloaf and Status Quo but nobody more famous than Marley.”

“The Marley gig is legendary around Phibsboro as gigs aren’t held in Dalymount anymore, big gigs … I thought it would be cool to do a shirt around that, not only with the music history but with Bob’s links to football as well.”

‘Revolution in music’

The concert even particularly carried resonance with one specific member of the club’s staff, according to Lambert.

“Lynn O’Neill, she is an employee of Bohs 40 years, She started working for Bohs in 1982. For the vast majority of those years, she was our sole employee on the non-football side.

“We were in the office yesterday and she said: ‘I was at that gig, I have photos at home.’

“She brought in some photos of the stage, really old photographs. There have been lots of them, who you know have been going to Bohs for years, talking about the gig.”

Pat Egan was the music promoter who had brought some of the most famous concerts to the country in that era, including the likes of Status Quo, Queen – and Marley.

He recalled the significance of Marley’s visit to not only the local community but to the country.

“I think Marley was the first really big international star to come to Ireland to play an outdoor show,” Egan said.

“Nobody of that kind of calibre was fronting a whole revolution in music … he was more than a rock figure, he was fronting a cultural revolution.”

Some of Egan’s memories of the day include seeing some of the crew and Marley’s band, the Wailers, playing football on the pitch in the lead up to the performance.

“They sound checked early in the morning and then they started playing football, first on the pitch until the groundskeeper said you can’t play around the goals.”

“The Wailers were definitely playing football as were the crew, Bob may have been on the sidelines,” Egan chuckled.

But what Egan remembers most vividly is his negotiations to bring the famed Jamaican songwriter to the country.

According to Egan, Marley had only one condition: the tickets had to be affordable for everyone.

“He dropped his price, I wanted to charge ten pound in. I was paying him big money [for the concert] and he said no, ten quid is too dear, let’s do seven pound [the country’s then currency] and he dropped his price by about $20,000 if I remember.”

“He didn’t want the fans to be overcharged. He was concerned. He didn’t want the fans to be overpaying so he agreed to a lesser fee,” Egan said.

‘Live for others, you will live again’

That generosity of spirit is what Bohs CEO Lambert also had in mind when he thought of the jersey idea.

He said the fact that some of the proceeds of the jersey sales were for a good cause made for a perfect tribute to Marley’s life and legacy.

It’s the reason, Lambert says, that Marley’s representatives and family were on board with the concept.

“The fact that we are not for profit, a co-operative, that there is no capacity for personal profit to be derived from the club … that’s really important.”

“It was something we were keen to point out [to Marley’s representatives] and it must have been received well, obviously, because they chose to do it with us.”

Some of the reggae star’s most famous lyrics were “live for yourself and you will live in vain, live for others, you will live again.”

It’s a message that Bohemians as a club seem to have modeled themselves on in recent years.

Off the pitch, the team has pursued a number of initiatives in recent years to help those in need and serve the greater good.

Last year, the club hired football’s first Climate Justice Officer in an effort to tackle the climate crisis.

In 2020, the club partnered with Amnesty International on the design of a new away shirt featuring an image of a family fleeing war and the message “Refugees Welcome.”

Every Christmas, the club also purchases gifts for children who are in Ireland’s asylum system. The club raised over 100,000 euros ($112,000) in those efforts just last month.

Lambert told CNN Sport that a lot of the steps taken by Bohs in recent years have only made the club stronger as a co-operative.

“Our membership from 1890 right through to about 2017, was always between 450 and 500 people … today the membership is just over 2,000 – mainly local people,” he said.

“The biggest change is perception. If you walk around the area with a Bohs top, everyone knows who we are. They are positively exposed towards us.”

He attributes the positive response of the public to a desire for community in an increasingly commercialized society, with Bohemians seemingly filling a void.

“A football club can really act as a lot of those pieces. It can be somewhere you go that has strong values that you feel proud of, you can link yourself to and go with friends or grandparents intergenerationally. A shared experience when those things are becoming less common.”

“We can’t guarantee what will happen on the pitch but we can guarantee how we act off it,” Lambert added.