Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Near the summit of Costa Rica’s Poás volcano is one of Earth’s most acidic lakes, bright blue and full of toxic metals.

The harsh conditions of Laguna Caliente, where temperatures can fluctuate between 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) and 194 degrees Fahrenheit (90 degrees Celsius), are where a few lucky scientists go to learn more about Mars.

Frequent phreatic eruptions occur when groundwater is heated by volcanic activity, releasing explosions of ash, rock and steam.

Yet microbes have found a way to live in this environment, one of the most hostile on our planet, according to multiple studies of the lake and new research published last week in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.

Although the diversity of the life in this lake isn’t high, it has managed to adapt and persist in a multitude of ways.

“Our finding shows that life persists in the most extreme environments on Earth,” said study author Justin Wang, graduate student and research assistant at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“It’s hard to imagine something more hostile to life than an ultra-acidic volcanic lake with frequent eruptions,” Wang said. “The low biodiversity coupled with numerous adaptations and metabolisms in our sample suggests the lake hosts highly specialized microbes for this kind of environment.”

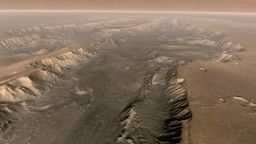

This otherworldly environment could suggest how life might have existed on Mars billions of years ago and reveal new places to search for evidence of ancient life on the red planet, according to the researchers.

A tale of two lakes

The two crater lakes near the volcano’s summit, both formed after craters filled with rainwater, couldn’t be more different from each other. One inactive crater holds Botos lake, which is surrounded by tropical vegetation. The active crater is home to Laguna Caliente, which contains liquid sulfur and iron. Gases from the lake create acid rain and acid fog, harming nearby ecosystems and irritating the eyes and lungs of intrepid explorers.

Researchers conducted active field studies at the lake in 2013, 2017 and 2019. While the results from the 2019 excursion are still pending, it’s a trip Wang will never forget.

Poás volcano, located in the middle of the Costa Rican rainforest, erupted most recently in 2017 and 2019. The area immediately around the volcano is devoid of life due to the toxic gases it releases.

Wang and his collaborators hiked to the volcano in November, a month after the crater lake reformed. They were mindful of where they stepped in the loose soil caused by acidity breaking down the surface material. Parts of the lake boiled and volcanic openings called fumaroles belched out hot sulfurous gases.

“When I went to the Poás Volcano, it was after over a year of magmatic eruptions and only a month after the lake reformed and it was deemed safe enough to return to the crater lake’s surface,” Wang said. “The lake itself is roiling and dynamic. As you get even closer, you can smell the strong stench of sulfur, which has remained on the clothes I was wearing to this day. Even worse is the smell of hydrochloric acid, which tastes sour in the air and stings the eyes.”

Surrounding the lake are puddles of boiling water and acid, and Wang felt the volcano’s heat through the bottoms of his shoes near the lake shore.

The researchers collected samples from the lake, just as they had in 2013 and 2017.

“It is a very intense and thrilling experience to sample from the lake,” Wang said. “I’m very lucky to be one of the handful of scientists in the world to have been able to visit this environment.”

Living on the edge

In 2013, the researchers determined that Acidiphilium bacteria lives in the lake. These microbes are often found in acid mine drainage as well as hydrothermal systems, like Laguna Caliente. Acidiphilium bacteria have multiple genes that allow them to adapt to survive across different environments.

More eruptions occurred at the site before the team returned in 2017. After gathering more samples, the researchers found that there was a little more biodiversity among the bacteria in the lake than expected. Additionally, their DNA sequencing revealed that the Acidiphilium bacteria has developed ways to convert elements like sulfur, iron and arsenic to create the energy needed to survive.

“Between 2013 and 2017, there were numerous phreatic eruptions that influx toxic metals, extreme acidity, and heat to the lake, but nevertheless we saw some of the same microorganisms in the same environment,” Wang said.

About a month after the team collected samples from the lake in March 2017, the Poás volcano erupted with magma. The force of the explosion hurtled rocks over a mile away from the site, spewed lava, drained the crater lake and released an ash plume about 12,000 feet above the crater multiple times, said study coauthor Geoffroy Avard, volcanologist at the Volcanological and Seismological Observatory of Costa Rica.

“We would like to characterize how life reclaims this environment,” he said. “A main hypothesis from our study is that life in the Poás Volcano is able to survive on the fringes during these extreme environments. So we’d love to sample not only the crater lake but the shore line, connected groundwater systems, and anywhere where life might be harbored nearby.”

The search for life

The genetic adaptations discovered by Wang and his colleagues during their study suggests that life could have survived in hydrothermal environments on Mars much like it does in some of the most extreme places on Earth.

Hydrothermal systems provide heat, water and energy – all necessary for the formation and evolution of life. While previous Martian exploration has looked at ancient sources of water like craters and rivers, the researchers think that the sites of ancient hot springs are another key target in the search for extraterrestrial life.

“These places are not hard to find since early Mars had rampant volcanism and abundant near-surface water,” said study coauthor Brian Hynek, associate professor at University of Colorado Boulder’s department of geological sciences and a research associate at the university’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, via email.

“In fact, we have discovered many ‘dried up Yellowstones’ across Mars, based on sulfur-bearing mineral signatures detected from orbit,” he said.

The NASA Spirit rover even came across a volcanic vent when it explored Mars between 2004 and 2011, Hynek noted.

“The crater rim of the Jezero Crater, where the Perseverance rover is now, is a place that likely exhibited hydrothermal activity due to the crater-forming impact that occurred, so I’d be curious to see what results Perseverance finds when it reaches there,” Wang said.

Research to understand the tiny organisms that live in extreme environments is changing how scientists regard the limits of life, whether it be within an active volcanic crater lake or along hot hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor.

While that helps researchers change the way they think about how life might exist within the hostile conditions on other planets, Wang warns that scientists shouldn’t be too “Earth-centric” in their approach. Life on Earth is usually found in the presence of water, but the existence of water on Mars was much more limited and episodic in the past, he said.

“I think we need to change the way of how we think of life on other worlds,” Wang said. “We need to consider the unique geological histories of our extraterrestrial environments and put that in context with what we have here on Earth. If rivers were unstable on Mars while hot springs were common, then perhaps life in hydrothermal environments is the most likely place where life could have existed.”