Editor’s Note: Amy Bass (@bassab1) is professor of sport studies at Manhattanville College and the author of “One Goal: A Coach, a Team, and the Game That Brought a Divided Town Together” and “Not the Triumph but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete,” among other titles. The views expressed here are solely hers. Read more opinion on CNN.

As Olympic mic drops go, China just raised the bar with a cauldron-lighting surprise that openly acknowledged the layers of political meaning at play.

The Olympic torch entered the stadium after International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach’s welcome at Friday’s Opening Ceremony of the XXIV Olympic Winter Games in the hands of speed skater Zhao Weichang, the first of seven torch bearers, who emerged in order of the decade in which they were born.

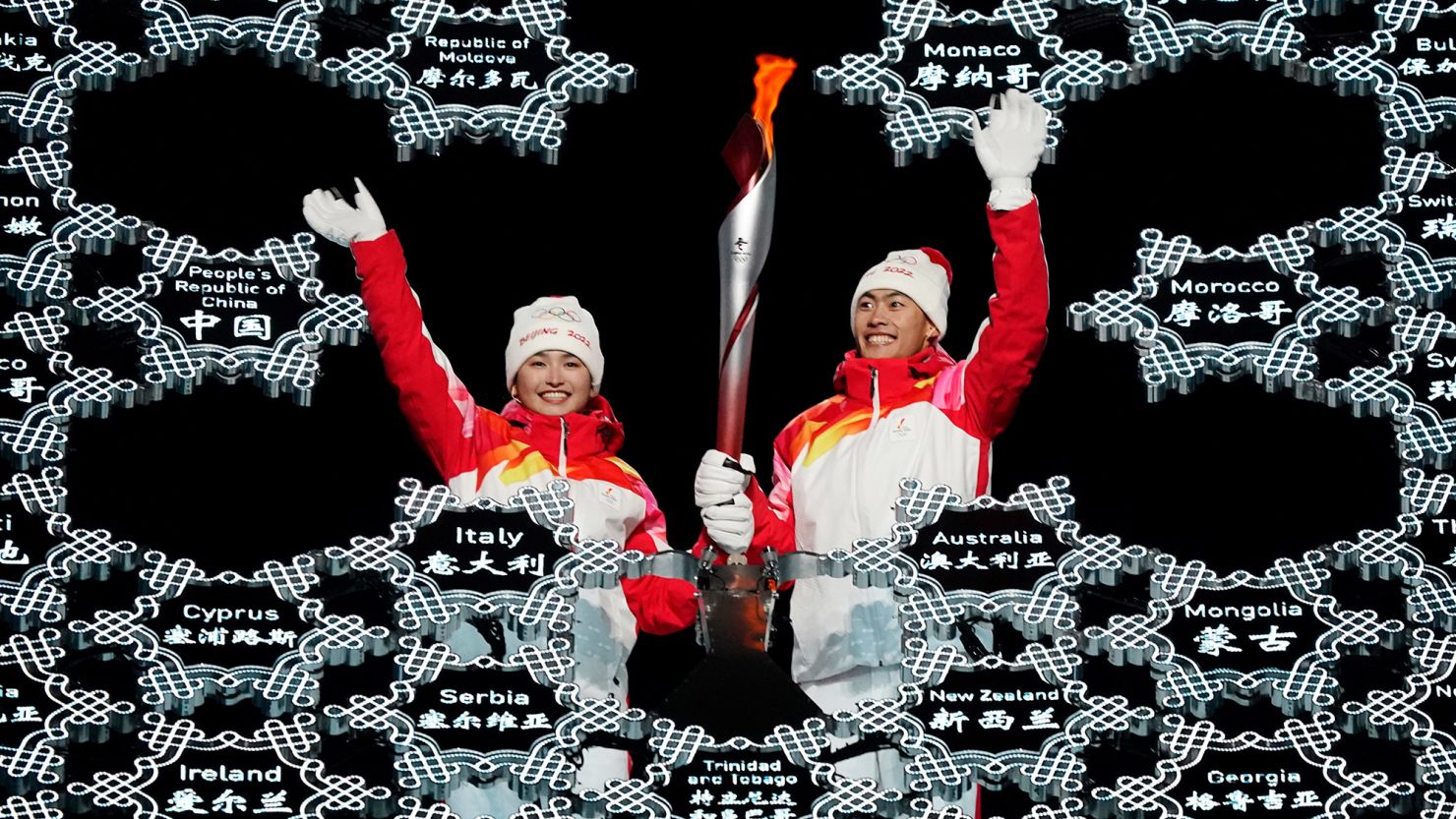

The torch relay finished in the hands of two Olympians competing in Beijing: One was Nordic Combined athlete Zhao Jiawen. The other, in a nod to gender equity and one of the political controversies at the center of these Olympics, was cross-country skier Dinigeer Yilamujiang, who hails from Xinjiang and who the Chinese state media said has roots in the Uyghur minority, whose plight has been central to the diplomatic boycott of these Games by the United States and other nations.

As the two lit the cauldron together, the message was clear to the many countries who refused to send dignitaries to Beijing: These Olympic Games are our moment, not yours.

Amid layers of political symbolism, many firsts

Injecting the lighting of the Olympic flame with layers of political meaning and symbolism is nothing new. Cathy Freeman represented aboriginal Australia in Sydney in 2000. US Cold Warrior Mike Eruzione and his 1980 hockey teammates – who took down the Soviet Union’s legendary team on the ice after that country’s invasion of Afghanistan – performed the honor in Salt Lake City in 2002.

In no uncertain terms, the spotlight on China’s legacies of human rights violations has been nothing short of rightfully intense. But from the waving athletes to the male-female duos bearing each delegation’s flag, there was, to be clear, also much joy to behold during the opening ceremony to these Games, which marks the first time a city has hosted both summer and winter Olympics.

Just as Tokyo gave the world a somber but hopeful start to its Games, Beijing’s ceremony, again in the hands of Oscar-nominated director Zhang Yimou, presented a more subdued pageant than we saw in 2008, with a fraction of the number of performers on the floor of National Stadium – the Bird’s Nest.

Gone were the 2,008 drummers that made the Opening Ceremony 14 years ago so memorable. In their place was a lightshow peppered by winsome children filled with song, and most of the pageantry that followed took on a snowflake theme.

Volunteers brandished large snowflake-shaped signs to bring the athletes into the stadium: 91 teams who field 2,900 athletes in 109 medal events – seven of which are new to these Games. As always, the Parade of Nations gave each squad a chance to show its best face. With Tokyo 2020, the IOC began the tradition of a male-female duo carrying each flag, but for some countries – 19 in all – who field just one athlete, this was not possible.

American Samoa featured sledder Nathan Crumpton, who took up the legacy of Tongan crowd favorite Pita Taufatofua (who stayed back home in Tonga to help with disaster relief) and walked into the stadium shirtless and oiled up. Skier Sarah Escobar, a student at St. Michael’s College in Vermont, carried the flag for Ecuador, becoming the country’s first female athlete in a Winter Olympics.

Despite good gender optics during the ceremony, gender equity in the Winter Olympics has a way to go. While Tokyo became the first to achieve near parity along gender lines, the Winter Games, continue to lag. In Beijing, women will comprise nearly 45% of athletes, a 4% increase from 2018. Men have more events on the winter program – 51 as opposed to 46 for women – and compete in the Nordic Combined, the only Olympic sport not open to women. The large men’s field in hockey – 12 teams include some 300 players while the women’s side will see 10 teams and just over 200 athletes – also contributes to the imbalance.

In Beijing, gender stretches beyond male-female equity of representation to include more nuanced understandings of identity (and competition). American figure skater Timothy LeDuc will become the first non-binary Winter Olympian to compete, partnering with Ashley Can-Gribble in the pairs competition. Additionally, there will be more opportunities for men and women to compete together. While nine new gender-mixed events launched in Tokyo last summer, Beijing will build on events such as team figure skating with the debut of a mixed relay in short track speed skating, as well as mixed events in ski jumping and snowboard.

The whole world is looking, but will they be watching?

But despite all of these exciting firsts, the ceremony – designed as one of the key rituals that separate everyday life from life during an Olympics – can only do so much in a moment when the world is, collectively, exhausted. While the Covid-19 pandemic has thrown a spotlight on every ill humanity faces, from global public health inequities to disinformation and pseudo-science, the virus is but one specter haunting China.

Russian leader Vladimir Putin, seated alone but not far from China’s President Xi Jinping (earlier the two had had a seemingly warm meeting together), stood to applaud hockey player Vadim Shipachyov and speed skater Olga Fatkulina carrying in the flag of the Russian Olympic Committee, rather than the nation’s flag. Beijing marks the third and last time Russian athletes, some 200 strong in Beijing, will compete in this manner, serving out the end of a ban instituted for doping violations.

But Russia’s past doping scandals are barely a headline at this point, pushed onto one of the world’s many backburners by the thousands of troops amassed on Ukraine’s border. Ukraine selected freestyle skier Oleksandr Abramenko, who won gold in aerials in 2018 and marks his fifth Olympic appearance in Beijing, and ice dancer Oleksandra Nazarova for the honor of carrying its flag with its team of 45.

Before competition even began, Ukrainian officials warned its athletes to avoid social contact with members of the Russian team, perhaps especially in photos. Last August in Tokyo, Ukrainian Yaroslava Mahuchikh, who took bronze in the high jump, drew the ire of many back home for a celebratory photo with Russia’s Mariya Lasitskene, the gold medalist in the event.

The political tensions between the two countries have, without question, leaked into China’s ‘closed loop’ Olympic bubble, regardless of Bach’s appeal in his welcoming remarks to “all political authorities across the world [to] observe your commitment to this Olympic truce.” Bach’s pleas match those of just about every other IOC leader in history – including Avery Brundage, who in 1936 shunned the idea of a boycott of the Games hosted by Nazi Germany because “the Olympic Games belong to the athletes and not to the politicians.”

Russia, especially, is no stranger to this kind of tension bleeding into the Olympics – sometimes quite literally. The Melbourne Olympics in 1956 saw Hungary defeat the Soviet Union 4-0 against the backdrop of the Hungarian Revolution, dubbed “blood in the water” after Soviet player Valentin Prokopov punched Hungary’s Ervin Zador in the eye in the final minutes of the game. In 1968, Czech gymnast Věra ?áslavská noticeably averted her eyes away from the Soviet flag and anthem during medal ceremonies, protesting the Soviet invasion of her country.

In 2014 during the Sochi Olympics, Ukrainian athletes asked to wear black armbands when protests against Viktor Yanukovych’s administration turned deadly, while others left the Olympics in solidarity of those fighting in the streets of Kyiv. At that time, Bach urged Ukrainian athletes to demonstrate how “sport can build bridges and help to bring people from different backgrounds together in peace.”

Putin’s own relationship with the Olympic Games, too, should not be forgotten. In 2008, whether by coincidence or design, Russia invaded Georgia, taking over South Ossetia, just as the Olympics got started. Just three days after the conclusion of the Sochi Games, he seized Crimea.

Whether or not those Russian troops step over the line during these Games is anyone’s guess, especially with speculation that Xi has asked Putin not to take the limelight off the Olympics. Not exactly flush with friends, Putin might hold off while Xi has his party. But if not, the world that watched this Opening Ceremony might not be the same as the one that watches Closing.

With that in mind, did this Opening Ceremony provide enough light, enough hope, to illuminate the dazzling quad jumps of six-time US figure skating champ Nathan Chen, who hopes to rectify his disappointing finish in PyeongChang (and is off to a good start, if his short program in the team competition is any indication)? Can we make room amidst masks and nose swabs and vaccination cards and isolation to root for snowboarder Chloe Kim, the first woman to land a front-side double cork 1080, making her to the mountain what Simone Biles is to the vault?

We shall see. The most important question may not be whether we care about these Olympics – the thrill of competition on ice and snow on display mere months after the end of the Tokyo Games. It might be whether or not we have the energy to care about anything.