Russia has one obvious ally to turn to as geopolitical sparks fly with the West over Ukraine.

But don’t expect China to offer much more than supportive words to its northern neighbor should the United States and Europe follow through with threats to slam Russia’s economy if Moscow launches an invasion of Ukraine. Beijing’s diplomatic and military ties with Moscow may be strong, but its economic allegiances are a lot more complex.

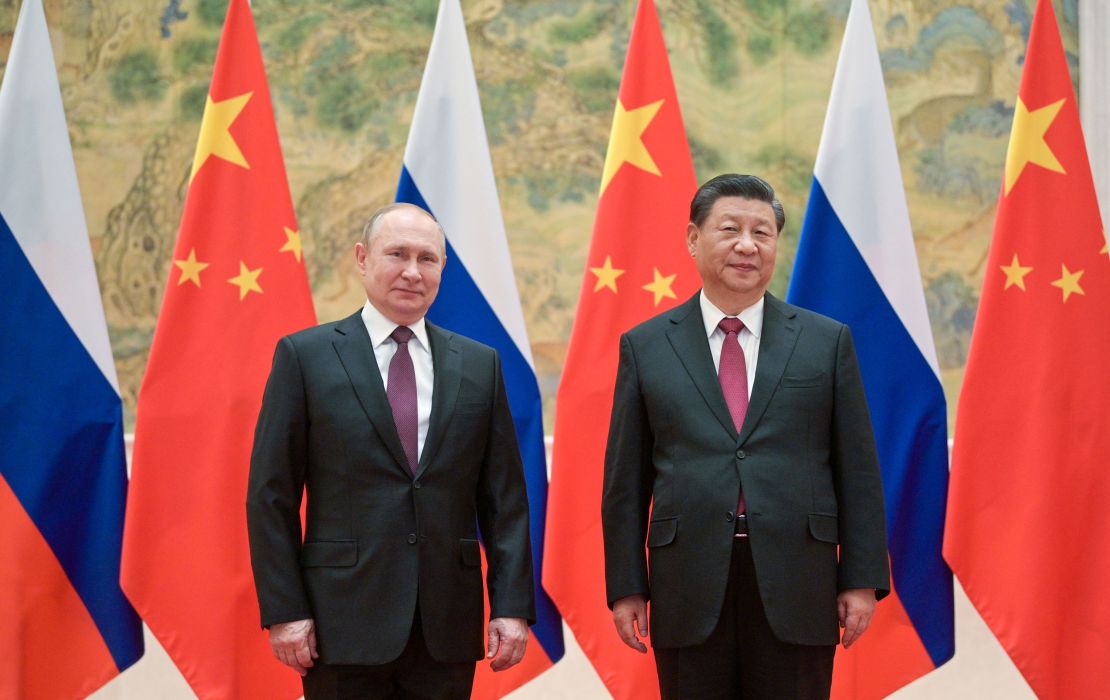

Russian President Vladimir Putin met his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping on Friday as the Beijing Winter Olympics kicked off. The Kremlin described the meeting as warm and constructive, and the leaders agreed to deepen their cooperation, according to an account published by Chinese state news agency Xinhua. Russian oil giant Rosneft said it had agreed to boost supplies to China over the next decade.

“Working together, we can achieve stable economic growth … and stand together against today’s risks and challenges,” Putin wrote in an op-ed published Thursday by Xinhua.

Those risks may be formidable should Russia invade Ukraine. Moscow has denied that it has any intention of doing so.

But US lawmakers are threatening to impose what they call the “mother of all sanctions” on Russia should it cross a red line. European leaders are also preparing punishments that would go way beyond the curbs imposed on Russia when it annexed Crimea in 2014.

China — which has its own tensions with the West — has already expressed diplomatic support for its ally. In a joint statement issued Friday after their meeting, Xi and Putin said both sides opposed “further enlargement of NATO.” Russia fears Ukraine may join the alliance.

“Xi almost certainly believes there is a strategic interest in supporting Russia,” said Craig Singleton, senior China fellow at the DC-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies. He pointed out that China “remains at permanent loggerheads” with the United States.

There is already some evidence that tensions with the West have deepened cooperation between China and Russia, according to Alexander Gabuev, senior fellow and chair of Russia in the Asia?Pacific Program at Carnegie Moscow Center. He cited arms deals, the joint development of weapons, and an “increased number of joint drills” between the two powers.

But it’s not clear how far that would extend to deeper economic cooperation in the face of harsh sanctions. Russia depends deeply on China for trade, but that’s not the case the other way round. And the Chinese economy is already in a shaky spot, giving less incentive to Xi to tie his country’s fortunes to Moscow’s in the event of a military crisis.

“It would be a ‘win’ for Putin if Xi simply hews closely to China’s stated desire for a diplomatic resolution to the crisis, as it implies that Putin’s grievances are legitimate,” Singleton said. “Beyond that though, China may be hard pressed to truly deepen its economic ties with Russia, at least any time soon.”

Russia needs China for trade. China has other priorities

China is Russia’s No. 1 trading partner, accounting for 16% of the value of its foreign trade, according to CNN Business calculations based on 2020 figures from the World Trade Organization and Chinese customs data. But for China, Russia matters a lot less: Trade between the two countries made up just 2% of China’s total trade volume. The European Union and the United States have much larger shares.

“Beijing needs to be very cautious about wading into a conflict between NATO and Russia over the Ukraine,” said Alex Capri, a research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation. “China’s current economic ties with Russia, including its energy needs, don’t warrant Beijing risking further alienation and backlash from Washington and its allies. This could come back to haunt Beijing later.”

Western authorities know the stakes are high for China, too. Last month, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken warned Beijing that an invasion of Ukraine would create “global security and economic risks” that could also hurt China.

China’s economy is already struggling, which could make it harder for Beijing to deepen ties with Moscow — or even deliver on promises it has already made, such as a recent agreement to boost China-Russia trade to $200 billion by 2024, roughly $50 billion a year more than it does now.

The International Monetary Fund expects China’s economy to grow by just 4.8% this year, down from 8% in 2021. A real estate crisis and subdued consumer spending are dragging the rate of growth down.

Singleton said that an escalating crisis in Ukraine would “almost certainly shock” energy and metals markets, thus weighing heavily on the global economy. That kind of emergency, coupled with China’s strict zero-Covid policy, “could hasten China’s already rapid economic slowdown.”

There are limits to Beijing’s help

A strong relationship with China would likely only mitigate rather than neutralize the impact of Western sanctions on Russia, according to Capri of the Hinrich Foundation.

And there are some problems that China can’t really help with at all, he added.

Take the “nuclear option” that could upend the Russian economy, for example. The West could remove the country from SWIFT, a high security network that connects thousands of financial institutions around the world. That could cut Russia off from the global banking system.

The Chinese yuan is “nowhere close to being sufficiently internationalized to compete with the US dollar,” Capri said, noting that the dollar plays a critical role in both SWIFT and also the trading of commodities such as oil and gas, the “lifeblood of Russia’s economy.”

Analysts at Eurasia Group wrote in a report last week that Beijing could redouble efforts to build a yuan-denominated payment system, which might allow it to do business more freely with countries that have been sanctioned by the West without using dollars or euros.

Even so, they wrote, companies in both China and Russia “still prefer to denominate trade in freely convertible currencies,” meaning that any efforts to reduce Western influence would be “more aspirational than substantive.”

Recent history isn’t in Russia’s favor. After Russia invaded and annexed Crimea in 2014, the country pivoted to China for support as it was slapped with economic sanctions.

And even though Beijing publicly opposed those punishments and promised to boost economic ties, its efforts weren’t enough to offset Russia’s problems.

Trade between Russia and China in 2015 fell 29% from the year before, according to official statistics from China. Chinese direct investment into Russia also suffered.

And Russian bankers complained that Chinese banks were reluctant to do business with them so as to avoid violating the sanctions, according to a 2015 op-ed written by Yuri Soloviev, the deputy president of VTB Bank, a major Russian financial institution.

“China is the senior partner in the bilateral relationship,” wrote the Eurasia Group analysts in their recent report, pointing out that the economy is about nine times larger than Russia’s. “It is likely that Beijing wants to shape Moscow’s calculus to its advantage.”