In the parking lot of a refugee reception center just inside Poland, Ukrainian women spoke last week with a bus driver as aid worker Chris Skopec stood nearby.

“It looks like I’m going to Germany,” one of the war refugees told Skopec as she laughed hysterically. “How ridiculous is that?”

Then, the next moment, the woman was weeping, Skopec recalled. Her husband and two sons were still far inside Ukraine, where humanitarian needs were burgeoning amid Russia’s bombardment. Here she was, at the first meager waypoint on her migrant journey. And if she took this ride, she’d be headed into the unknown, unsure where she’d even sleep.

“And she got on the bus,” Skopec, executive vice president of global health for Project HOPE, told CNN. “That’s everyone’s story.”

More than 3 million people have fled Ukraine since the invasion began more than three weeks ago, according to the International Organization for Migration, or IOM, and legions more flee to the border every day. Meantime, many more of Ukraine’s 45 million residents remain in a country where active conflict has cut off access to basic supplies like medicine.

To serve their needs, the United Nations and its partners on March 1 launched an emergency appeal for $1.7 billion. Of that, $1.1 billion would go toward helping 6 million people inside Ukraine over the next three months and nearly $551 million help support Ukrainians who fled to other countries in the region.

Aid groups are working now to address the massive humanitarian crisis – inside Ukraine, along the country’s borders and in places of refuge far beyond. At each stage, Ukrainians face distinct needs, aid officials have found, and delivering proper resources at each one is no easy task.

How to help the people of Ukraine

Inside Ukraine, everything is needed

The need for medical supplies inside Ukraine is so great that Skopec stopped compiling lists. Every hospital is saying the same thing, he told CNN: “We’re running out of everything.”

He and a Project HOPE team traveled last weekend into Ukraine to deliver a shipment of medical supplies to a 4,000 bed, three-hospital network in Lviv. Among the supplies were specialized sutures used in a heart transplant the very next day, he said.

“Of course, we can talk a lot about the life we saved there, but this is a country of 45 million,” he said. “So, we won’t and can’t stop with the idea of just helping one person.”

Resupplying health care facilities – and the doctors, nurses and support staff now doing their jobs in a war zone – is the principal focus of Project HOPE’s efforts inside Ukraine, said Skopec. The 64-year-old organization’s mission is supporting health care workers around the world.

But as the demand for health care services inside Ukraine is greater than ever, the nation’s supply chain has been severely disrupted, Skopec told CNN. He compared the needs to those of American doctors and nurses at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic: In Ukraine, health care workers in clinical settings are running out of masks and trauma supplies.

Another aid group, Americares, has sent 3 tons of critical medicine and medical supplies to Ukraine, its vice president of emergency programs, Kate Dischino, said in an email. And it’s working on getting more.

“We are getting requests from health care facilities in Ukraine running low, or stocked out of, the most essential supplies,” she said.

There’s a heavy emphasis on trauma supplies like bandages and antibiotics due to the fighting, with at least 1,333 people injured as of Friday, per the UN Human Rights Office.

But there are also people with chronic conditions who need continued access to care and medicine – and primary care inside Ukraine is functionally nonexistent, Skopec said. For instance, an estimated 2.3 million people in Ukraine, or 7.1% of the population, live with diabetes, according to the International Diabetes Federation. And some 10,000 people in Ukraine depend on dialysis to live, several global nephrology groups said in a joint statement.

“Beyond the direct causes of conflict … you have all of the emergency needs that every population on the earth has,” Alex Wade, a Doctors Without Borders emergency coordinator told CNN on Monday. “You have people who need access to insulin, people who need access to dialysis. You have pregnant women who need access to safe deliveries and, who could have complicated pregnancies, need access to surgical services. You have people with serious mental health conditions that need access to mental health services.

“These are all conditions where, if access is interrupted, the condition can deteriorate … leading to serious complications or death,” Wade said.

And needs extend beyond medicine: Food is the most urgent one now for the Odesa Humanitarian Volunteer Center, said Inga Kordynovska, head of the group that launched after the invasion. On top of supporting locals in the port city, refugees are pouring in from other Ukrainian cities like Kherson and Mariupol, she said.

Still, the nature of the conflict means there are large swathes of Ukraine where it’s extremely difficult – or impossible – to deliver humanitarian aid.

At borders, safe passage is planned for the weary

Ukrainians escaping active conflict flee to the nation’s borders, where their needs are distinct from those inside the war zone – but just as pressing. Many tell similar stories: They left their homes on short notice, grabbing what they could and embarking on dayslong journeys. Some ran out of fuel or found it heavily rationed. At the border, they faced lengthy waits to cross.

“They’re coming across exhausted, scared, angry,” Skopec said.

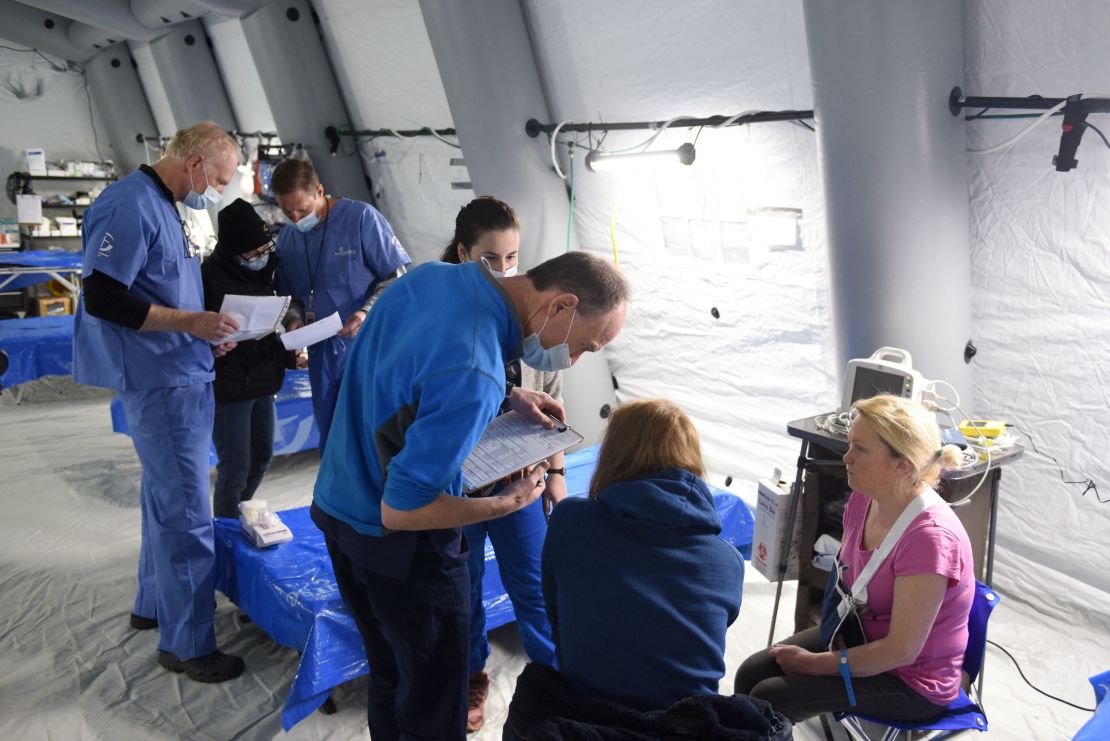

Some have medical problems that must be addressed immediately: exhaustion, dehydration or gastrointestinal problems. Project HOPE buys and distributes medical supplies to clinics and temporary shelters that receive refugees, Skopec said. It also provides hygiene kits to support public health – and refugees’ dignity.

At border crossings to Poland and Romania, humanitarian workers support a refugee population still in transit, Skopec said. They move on quickly, getting tickets for buses or trains to take them further into Europe. More than 200,000 people entered Romania from Ukraine between February 24 and Wednesday, according to the IOM. The Romanian Ministry of Internal Affairs’ state secretary on Tuesday put that number at 425,000, saying most had moved on to other countries.

Aid workers at border crossings register refugees so assistance can be better targeted to their needs – a challenge in itself. CARE International is among aid partners working within existing civil infrastructure to register refugees, particularly those with extra vulnerabilities, and share it with other vetted organizations, like resettlement agencies.

“In the chaos of mass displacement,” it’s difficult to register everyone, CARE’s humanitarian communications coordinator, Lucy Beck, told CNN from Isaccea, Romania, along the Danube River at the Ukraine border. “So the aim is really to put in place systems and registration to catch as many people as possible.”

CARE’s focus on women and girls is also key: 9 in 10 fleeing violence in Ukraine are women and children, according to the UN’s Children’s Fund, or UNICEF. Ukrainian men between the ages of 18 and 60 are banned from leaving the country and must stay to help fight the Russian invasion.

Part of CARE’s mandate is protecting women and girls from gender-based violence, like rape or trafficking – a risk as they move from one country to the next, Beck said. For example, many people have offered transportation to refugees, and while that’s generous, it could also open refugees up to trafficking.

“There may be predatory people who will be taking some of these women and girls away,” UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs Martin Griffiths told CNN. “That’s an added, indecent part of this terrible conflict.”

In Sighet, another Romanian border city, anyone offering refugees transport must register with aid workers so they – like the refugees they’re ferrying – can be kept track of, Beck said. Meantime, vulnerable people, like unaccompanied children, are given specialized transportation services, she said.

Volunteers and translators doing this work interact with a huge volume of people, Beck said. Needed, too, are counselors and social experts who can support those in distress or confused to keep them away from potentially dangerous situations.

Border crossings are also filled with tearful goodbyes, and it’s not just men. Beck met a 22-year-old woman who dropped off her 84-year-old grandparent at the border – and then went back, she recalled.

“She was absolutely turning around straightaway to go back and volunteer,” Beck said. “Should it come that she (is) needed to fight, she was willing to do whatever it took, I guess, to stay and help the people in Ukraine rather than choosing to leave and go somewhere safe.”

Far from home, entire lives must be reset

Refugees are not just working to overcome short-term challenges – they’re faced with medium- and long-term needs, as well. And the shock of leaving their homes on such short notice could reverberate for years.

Warsaw alone had welcomed 300,000 people in the two weeks that ended Tuesday, Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski said. The city, he said, will help refugees, “but we are slowly becoming overwhelmed, and that’s why we make a plea for help.”

“If you think about all the things that you do as a normal person in your hometown, all of those things need to be … recreated for people in another country,” Beck said. Adults need to jobs and language skills to help to find employment; children need school.

Of the more than 3 million refugees who have fled Ukraine, Poland has by far received the most, at more than 1.8 million as of Wednesday, per the IOM. Hundreds of thousands more have entered Romania, Slovakia, Moldova, Lithuania and countries even further west, including Hungary, Austria, Germany, Belgium, Denmark, France, Portugal and the Netherlands, among many others, officials from those countries have said.

Refugees have also arrived in Italy, where two Ukrainian schoolchildren from Lviv got a warm welcome from their Italian classmates after arriving to live with their grandmother.

Refugees also need continued medical care, and the mass displacement has prompted a disruption in care for chronic diseases like HIV and tuberculosis, Doctors without Borders’ emergency program manager, Kate White, told CNN. Medications for these conditions might be available for free or cheaply in Ukraine but are more expensive in other countries, she said.

“There is going to be a significant burden, either on the individual or on the government that welcome this population to ensure that they can have continuity of care,” White said.

Already, for instance, 16 Ukrainian patients whose treatment was interrupted by the invasion are getting care in Italy, the country’s Civil Protection Department said Monday. Among them are nine pediatric patients in the Lazio, Emilia-Romagna and Lombardy regions.

And Krakow Children’s Hospital, which has had a decadeslong partnership with Project HOPE, is moving to open a separate ward for Ukrainian children, with Project HOPE contributing supplies and pharmaceuticals and installing equipment, Skopec said.

For those who want to help, aid organizations need monetary donations more than relief supplies. As well-meaning as the donation of medical supplies, hygiene kits and other items might be, money allows humanitarian groups to most efficiently direct their resources, Skopec said.

With cash, organizations like CARE “can look at that short-, medium- and long-term assistance,” Beck said, “and working with all the other NGOs and UN, identify the gaps in those different areas and sectors, so that we can work together to make sure everything’s covered across different needs.”

CNN’s Theresa Waldrop contributed to this report.