On the steps of a Darwin courthouse at the end of one of Australia’s most contentious cases, Warlpiri elder Ned Jampijinpa Hargraves could barely contain his rage.

“When are we going to get justice? When?” he yelled.

White police officer Constable Zachary Rolfe had just been acquitted of murder in the killing of 19-year-old Kumanjayi Walker, who Rolfe shot three times after Walker stabbed him during his attempted arrest in Yuendumu, a remote Aboriginal community in the Northern Territory.

After Walker’s death in November 2019, Indigenous people and their allies marched through the streets of several Australian cities, carrying signs reading “Justice for Walker.”

More than two years later, Rolfe’s acquittal on March 11 on three charges including murder and two lesser charges – manslaughter and engaging in a violent act resulting in death – has them questioning why justice still isn’t being served.

No police officer has ever been convicted in Australia of murdering an Indigenous person. In 31 years, since a landmark report into Aboriginal deaths in custody, nearly 500 Indigenous people have died in prison or police custody, according to the Australian Institute of Criminology.

The Rolfe verdict was about much more than one man killed during a three-minute confrontation in 2019.

For Australia’s Indigenous people, this case was about Australia’s record on racism and Indigenous rights, and what lies ahead for the county’s First Nations people, who say they’ve long been denied a say in the laws that govern them on land their ancestors lived on for tens of thousands of years.

An outback shooting

On November 9, 2019, Rolfe was one of five officers who set off on a three-hour drive to Yuendumu from Alice Springs, a remote town known as the staging point for tourist trips to Uluru, the sacred rock in the middle of the country of deep cultural significance to Indigenous people.

The officers were part of a team that responds to “high risk” incidents and they were specifically tasked with arresting Walker, who was wanted for breaching the conditions of a suspended sentence, according to court documents. After threatening police with an ax three days earlier, he was also wanted for alleged assault.

The officers had a detailed plan. They’d arrive on November 9 and attempt to arrest Walker first thing the following morning.

Instead, they opted to arrest him that night, and around 7:20 p.m., Rolfe and other officers followed a tip to a house, where they found Walker, court documents said.

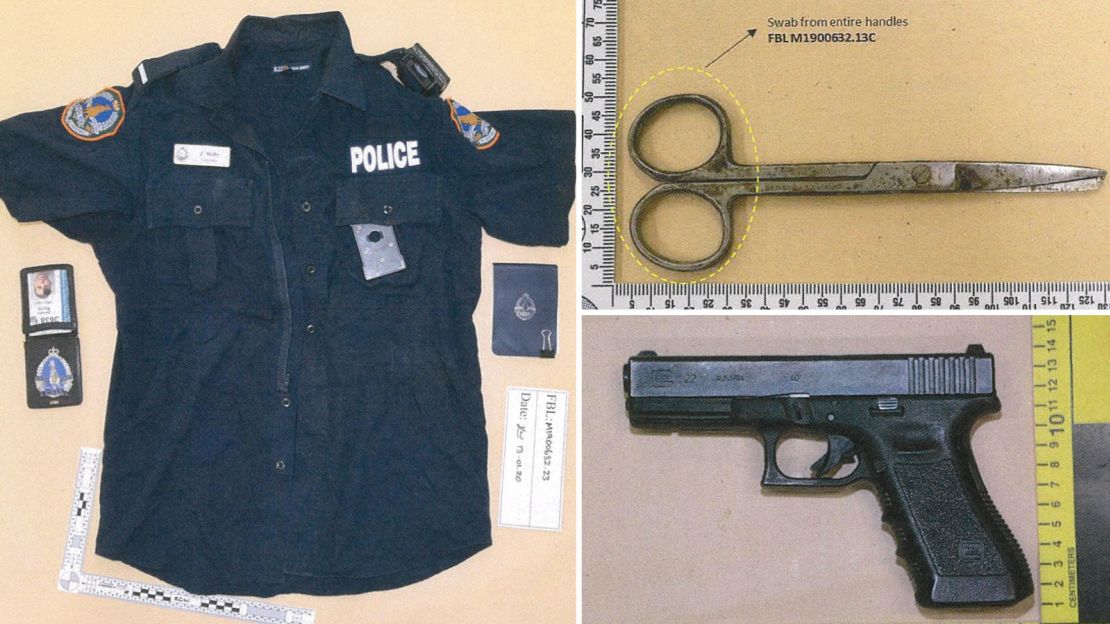

Bodycam footage released during his trial shows Rolfe approaching Walker in a darkened room and asking him, “What’s your name, mate?” When Walker realizes he is being arrested, he sinks a small pair of scissors into Rolfe’s shoulder. Then in quick succession, Rolfe fires his gun three times. “Either the second or the third shot was fatal,” court documents said.

Crown prosecutors accepted the first shot was in self-defense but argued the second two were excessive, as Rolfe’s partner had already restrained Walker. After deliberating for several hours, the jury accepted Rolfe’s defense that he only fired his gun to protect himself and his partner.

More than one man

The outpouring of grief over Walker’s death isn’t just about the loss of the teenager.

His death adds to the heavy toll suffered by Australia’s Indigenous community at the hands of White people since European settlers arrived and colonized the country in the late 1700s.

As settlers moved across the vast, arid landscape, they displaced the country’s traditional owners, rounded up some to work for little or no pay, and killed others, often in reprisal attacks over the deaths of White settlers.

“The data is telling us that the massacres after 1860 (were) being carried out on an immense scale,” said Professor Lyndall Ryan in a statement last week, as the University of Newcastle released its latest research on Australia’s frontier wars, conflicts fought between settlers and Indigenous people after colonization.

One of the last recorded massacres was in 1928 – in Coniston, about 43 miles (70 kilometers) east of Yuendumu – when Constable George Murray was sent from Alice Springs to arrest the Indigenous killers of dingo trapper Fred Brooks. Over three months, historians say Murray led search parties that killed at least 60 Aboriginal people, including those from the Warlpiri tribe – Walker’s people.

At the time, the killings created a national outcry that brought an end to state-sanctionedsearch parties.

But a board of inquiry set up to investigate the killings found that Murray, a World War I veteran, and his men had acted in self-defense. No one was tried or convicted.

For Hargraves, there are too many parallels between then and now.

“When we are at home at night, we sit by the fire and we tell the story of the histories of our ancestors, our people,” Hargraves told CNN. “Our loved ones were shot and they were terrified, they went scattered, everywhere.”

He says they’re still terrified that their children could be killed, like Kumanjayi Walker. “I don’t trust police to come into my house with a gun,” he said. “I don’t trust (the police) because I have children. I have grandsons, granddaughters.”

Call for no guns

Hargraves wants a ban on guns in Yuendumu and a return to the way he remembers from his childhood in the town in the 1960s and 70s, when police officers and locals knew – and trusted – each other.

But the suggestion of a ban on guns in remote Indigenous communities has been rejected by the territory’s Chief Minister Michael Gunner and the president of the Northern Territory Police Association Paul McCue, who both say officers need to be able to protect themselves. “To be quite frank, our members deserve to be safe in their workplace,” McCue said after the Rolfe verdict.

Between 2019 and 2020, the number of recorded assault victims in the Northern Territory rose by 22% to a 26-year-high, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Two in five assaults involved a weapon – the highest proportion of any state or territory.

But high crime rates conceal far deeper problems for Australia’s Indigenous communities. Despite numerous reports and recommendations, Indigenous people still have worse education, employment and health outcomes and a shorter life expectancy than non-Indigenous people. And they are disproportionately represented in the prison system – accounting for 30% of all prisoners though they only make up about 3% of Australia’s population.

Thomas Mayor, an author and Indigenous activist, says authorities need to make the connection between the trauma of the past and the experience of the present.

“There is a great disconnect from the experience of First Nations people in this country, disconnected to the reasons why the trauma in communities exists, the reasons why young men are committing crime,” he said.

Mayor says the bigger issue is that Indigenous people still aren’t being heard in national politics – and don’t have a say in making laws.

Indigenous groups across Australia are calling for the constitution to be changed so they’re formally consulted on legislation and policies affecting their communities.

That would require a national referendum, which requires political support before a yes-no question is put to the Australian people.

The last time Australians voted in a referendum on Aboriginal rights was in 1967 when 90% of the country supported a move to include Indigenous people in the Census.

Mayor says more progress is long overdue.

Back in Yuendumu, where the Warlpiri people are still mourning teenage Walker’s untimely death, they too worry about the future.

Hargraves says Yuendumu needs strong young people to pass on Aboriginal culture and traditions, for the benefit of the entire country.

“We love this country. In this whole Australia, we need to come together and to be one,” Hargraves said. “(Police) can’t keep on shooting our young people. We need young people to run this community – that’s what we want.”