The succession of Ketanji Brown Jackson, age 51, for Justice Stephen Breyer, 83, will add a shot of youthfulness to the Supreme Court and may present an opportunity for a reset at an institution whose reputation has slipped.

Five of the nine justices will be under 65, four of them of Generation X. They will be the face of the court in the upcoming decades.

For the immediate future, the addition of Jackson could prompt the court to reassess its response to diminishing public confidence. It has experienced a sharp drop in opinion polls. And the justices’ lack of transparency on recent procedural and ethical issues has accelerated criticism.

Chief Justice John Roberts has made clear his concerns about the integrity of the bench. He may believe – and be able to persuade his colleagues – that with a new justice in place, it is time to try to shore up public confidence, perhaps by formally adopting an ethics code.

A new junior justice, even one who is making history as the first Black woman on the court, would have limited impact within the marble walls. But, as Roberts has observed, a new justice can cause the rest to rethink old patterns.

“I think it can cause you to take a fresh look at how things are decided,” he told C-SPAN in 2009, in a rare expansive on-the-record interview. “The new member is going to have a particular view about how issues should be addressed that may be very different from what we’ve been following for some time.”

He was speaking about the substance of cases, but such a theory could hold for other practices at a life-tenured, black-robed institution that often seems behind the times.

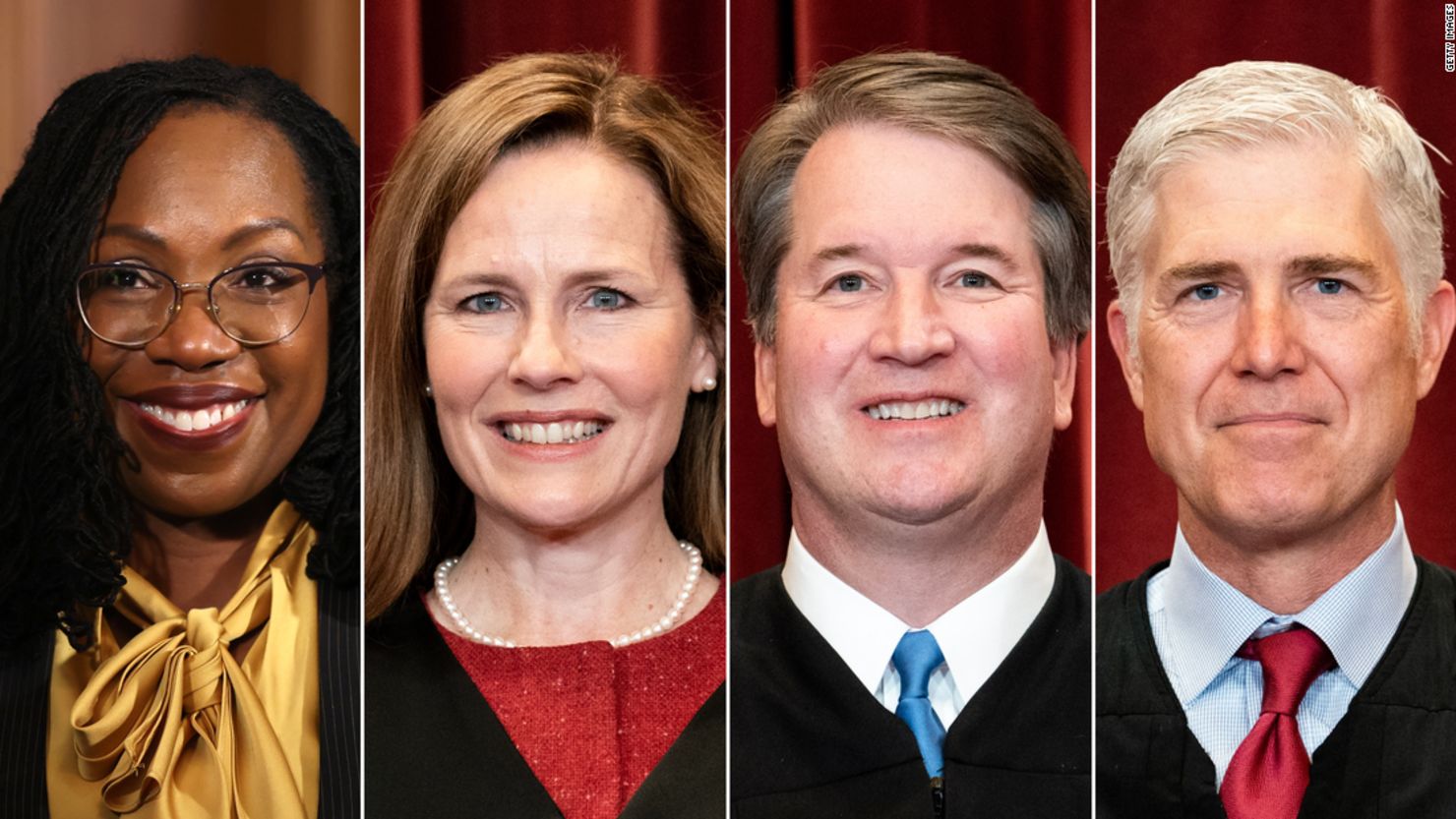

Jackson is 32 years younger than Breyer and of a different generation, which would naturally affect the dynamic around the justices’ private conference table. The 51-year-old Jackson will join fellow Gen X-ers Amy Coney Barrett, 50, Neil Gorsuch, 54, and Brett Kavanaugh, 57. Elena Kagan, at 61, is the only other justice under age 65.

Roberts and Sonia Sotomayor are 67, Samuel Alito is 72 and Clarence Thomas is 73.

The five younger justices will have mixed ideological approaches (three on right, two on the left), so it’s unlikely that a legal outlook unique to that relatively youthful bloc would emerge.

The court will be making several consequential decisions before Jackson officially takes her seat in late June or early July. Among cases already argued and being resolved behind closed doors are those over abortion rights, gun control and the separation of church and state.

None of the nine have commented publicly on new condemnation regarding their opaque recusal rules. Each justice decides when to sit out a case because of a conflict of interest, and no internal process exists to review those decisions. When justices recuse themselves, rarely is a reason made public.

Debate over the justices’ vague rules was sparked anew after revelations last month that Thomas’ wife, Ginni, texted with former Trump administration chief of staff Mark Meadows about reversing the results of the 2020 presidential election.

Justice Thomas participated in cases related to that election and voted three months ago in a dispute between former President Donald Trump and the US House select committee investigating the January 6, 2021, Capitol rampage, which had separately gathered Ginni Thomas’ texts displaying her belief that Biden was “attempting the greatest Heist of our History.” Justice Thomas was also the only member of the bench to publicly side with Trump in his effort to stop the National Archives last January from releasing White House documents to the January 6 committee.

“They have no code of ethics,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said at a news conference last week as the California Democrat responded to the Justice Thomas situation. “And really? It’s the Supreme Court of the United States. They’re making judgments about the air we breathe and everything else and we don’t know what their ethical standard is?”

The justices have objected in the past to such characterizations, insisting that they, in fact, consult ethics guidelines used by lower court judges. But as a group, they have failed to clarify exactly how they prevent conflicts of interest and declined to respond when queried about current ethics dilemmas.

A change behind the scenes

Jackson, who was confirmed by the Senate Thursday by a 53-47 vote, has served on lower federal courts since 2013, most recently on the prestigious US appellate court for the District of Columbia Circuit. In addition to her distinction as the first Black woman justice, she has rare experience as a former trial judge and federal public defender.

As a Democratic appointee succeeding Breyer, a liberal named by Democrat Bill Clinton in 1994, Jackson would not alter the current ideological balance of six conservatives and three liberals. But her singular background could enhance internal debate.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman justice, spoke of the “special perspective” of the first African American ever to sit on the high court, Thurgood Marshall, appointed in 1967.

Despite the opposition by all but three Senate Republicans, Jackson has garnered more public support than recent high court nominees.

Poll numbers for the Supreme Court have gone in the opposite direction. Gallup reported last September that the court’s approval rating had slipped to 40%, down from 49% in July, and the lowest since Gallup had been tracking court approval, back to 2000. The September poll was taken just after the court let a Texas abortion ban go into effect.

Barrett has demonstrated some worries over how the public views the court. She remarked to a Louisville, Kentucky, audience in September, according to local reports, “My goal today is to convince you that the court is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks.” This week at the Reagan Library in Simi Valley, California, she urged people to read the court’s opinions themselves to assess their legal validity.

But in some important cases, the conservative majority, including Barrett, has declined to explain its action.

That happened on Wednesday, the day after the Barrett speech, when the court reinstated a Trump-era policy related to the Clean Water Act. Kagan, joined by Roberts, Breyer and Sotomayor, chastised the majority for granting an unwarranted “emergency” request on the so-called shadow docket.

“That renders the Court’s emergency docket not for emergencies at all. The docket becomes only another place for merits determinations – except made without full briefing and argument,” Kagan wrote, as she and the others dissented from the action favoring Republican-led states, the American Petroleum Institute and other entities defending a Trump-era rule that limited the ability of states to block projects that affect the waterways within their borders.

Like Barrett and Roberts, Kagan has used public appearances to address the dilemma of preserving court integrity in these politically tumultuous times.

“The last thing that the court should do is to look as polarized as every other institution in America,” Kagan said in 2019 at the University of Colorado Law School, adding, “The only way to be seen as not that – is not to be that.”