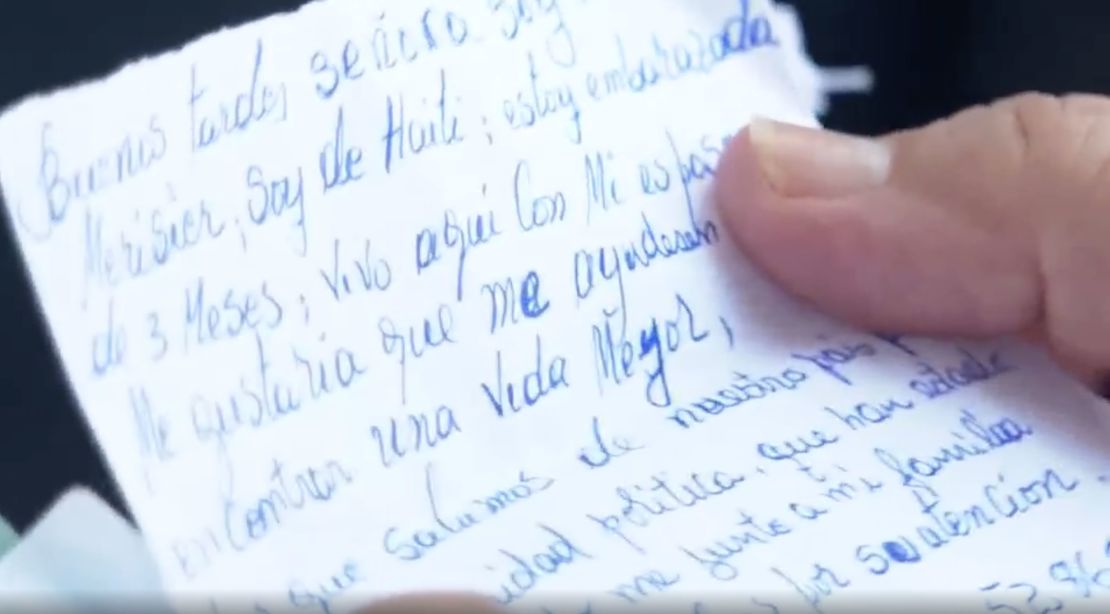

Migrants hand Sister Norma Pimentel little pieces of paper as she walks around the shelter where many of them have been living for months.

Some of the handwritten notes have their names and numbers. Others pen the horrors of the unfettered violence they escaped in their home countries or elsewhere in Mexico.

“It’s a life, every single one of them,” Pimentel says.

One of the most well-known migrant advocates in the Rio Grande Valley and director of the region’s Catholic Charities, Pimentel helps run respite centers and faith-based shelters, like Reynosa’s Senda de Vida, on both sides of the border, caring for thousands of people.

The stories on each paper she receives are different, but they all have one thing in common: the author was expelled by US immigration authorities to Mexico under Title 42 – a pandemic public health order that has been in place for two years and allows the US to send migrants, regardless of their nationality, to Mexico or back to their home countries.

The result in border cities is staggering to see. Shelters are packed with desperate people. There are also tent cities where some sleep with only tarps over their heads, without knowing where their next meal will come from.

They are in conditions that make vulnerable migrants – many of whom are fleeing violence and extortion in their home countries – easy prey for criminal organizations.

But their situation could soon change: The Biden administration’s recent announcement that it will be lifting public health restrictions at the border means migrants may have a chance to cross without facing immediate expulsion.

More than 7,000 migrants, mostly from Central America and Haiti, are waiting in Reynosa for Title 42 to lift, according to Pimentel. She is in contact with the Port Director of the Hidalgo International Bridge to coordinate a safe passage for them – the details are still being worked out, Pimentel says.

At least once a week, Pimentel visits Senda de Vida. She doesn’t know why migrants hand the notes to her, but she takes their stories and pleas for help to God, who she calls her “boss.”

“I just tell my boss, I say, ‘It’s your people. You have to guide me and tell me what I need to do to help them. If you think we can, show me the way,’” says Pimentel.

Now, there is renewed hope among those at the shelter – for an end to their agonizing wait and, at last, a shot at the American dream.

Nearly 10,000 cases of violence against migrants

Many of the migrants at the shelter were expelled by US immigration authorities to the foot of the international bridge that connects Hidalgo, Texas, and Reynosa, Mexico. It’s a dangerous plaza, according to Pimentel.

“It’s a space that is not protected,” she says. “The children are not safe; they can be taken (kidnapped) or the youngest could be raped.”

A migrant woman from El Salvador, who CNN will call Matilde, breaks down crying while talking about the plaza. (Pimentel asked CNN to not to name migrants due to the dangers they face in Reynosa and in their home countries.)

A few months ago, the plaza was taken over by heavily armed men wearing masks, Matilde says. She describes how her 9-year-old daughter was shaking with fear as the takeover unfolded.

Matilde still sees her daughter responding to the trauma of that day, even though time has passed, she adds.

“Sometimes when she is sleeping, she shakes and jumps up in fear. Believe me, we have gone through so many things during our journey (and) at the plaza,” she says.

Since President Biden took office, Human Rights First has identified nearly 10,000 cases of kidnapping, torture, rape or other violent attacks on people blocked or expelled to Mexico under Title 42.

The Trump administration put Title 42 in place during the early days of the pandemic, arguing the policy would stop the spread of Covid-19 – a claim some public health experts questioned. Many advocates expected President Biden would lift the order when he took office, given his campaign promises to build a more humane immigration system. Instead, his administration defended the controversial policy for months in court.

It wasn’t until March 2022 – more than a year into his presidency – that officials announced the policy would be lifted. That’s sparked concern among US politicians on both sides of the aisle, who fear the Biden administration doesn’t have enough of a plan in place to handle the expected increase in migrants at the border.

But here in Reynosa, time is a major concern for asylum-seekers. Migrants face danger every day, Pimentel says, and there isn’t enough shelter space to keep them safe.

The number of migrants in Reynosa is fluid and changes by the day, according to Pimentel. She estimates about 3,000 migrants are currently staying in the plaza – some with only a tarp to protect them from the elements and little to protect them from other dangers in this border city.

Migrants are helping build a new shelter while they wait

A Honduran woman’s face lights up as she proudly shows off her shovel. She’s part of a crew of migrants helping Pimentel build a new, larger shelter – with a capacity for 3,000 people – while they wait for a chance to enter the United States.

“For me, it’s a pleasure helping others,” says the woman, who CNN will call Nora.

Nora says she fled Honduras after gangs beat one of her daughters so badly, she lost the baby she was carrying. “I had to leave my home,” Nora says in a broken voice. “I own nothing.”

She’s been waiting on the border for more than a year for Title 42 to lift, Nora says.

Recently, she says she’s noticed the situation in Reynosa has started to change.

Before, most of the migrants at Senda were from Central America and Mexico. In recent weeks, Nora says Ukrainians have started arriving at Senda, too – and they have been allowed to cross the border after waiting only a few days.

The US Department of Homeland Security recently issued a memo telling border authorities to consider exempting Ukrainians from Title 42 on a case-by-case basis. That’s sparked criticism that the US is applying a double standard: letting Ukrainians in while many other desperate and deserving migrants are forced to wait. The head of DHS has denied that allegation.

Nora says she’s seen Ukrainians enter the US before the thousands of others from Central America, Haiti and other nations who have been waiting for months. But Nora says she’s not opposed to the exemption.

“We’ve only been threatened by the gangs,” Nora explains. “In Ukraine, there is war.”

‘Give us an opportunity’

For other migrants, the long wait has been devastating.

A woman hands Pimentel a piece of paper and breaks down crying. “I didn’t realize the American dream was going to turn to this,” she says.

Pimentel listens intently as the woman explains that she left her home country to reunite with her 17-year-old son in North Carolina. Her son, she says, wanted a better life in the US – and what else is a mother to do?

The woman’s parting words are a message for President Biden: “Give us an opportunity.”

Pimentel folds the piece of paper and stuffs it into a zippered purse she wears around her neck, along with the countless other messages she’s received.

“I’m hopeful that someone can listen to their story and hear the fact that they are hurting, and they need protection,” Pimentel says. “That’s all they are asking for.”

CNN’s Catherine E. Shoichet contributed to this report.