Mila Turchyn walks into a McDonald’s parking lot near the Poland-Ukraine border. She is anxious. She doesn’t trust the man she is about to meet. He is a smuggler.

Turchyn found the man via a messaging app a few days ago, advertising transport services for Ukrainians stranded in Russia. They made a deal– $500 to drive Turchyn’s mom and sister from Moscow to Przemysl, Poland. It’s more than most families fleeing war can afford.

She is wondering if it worked.

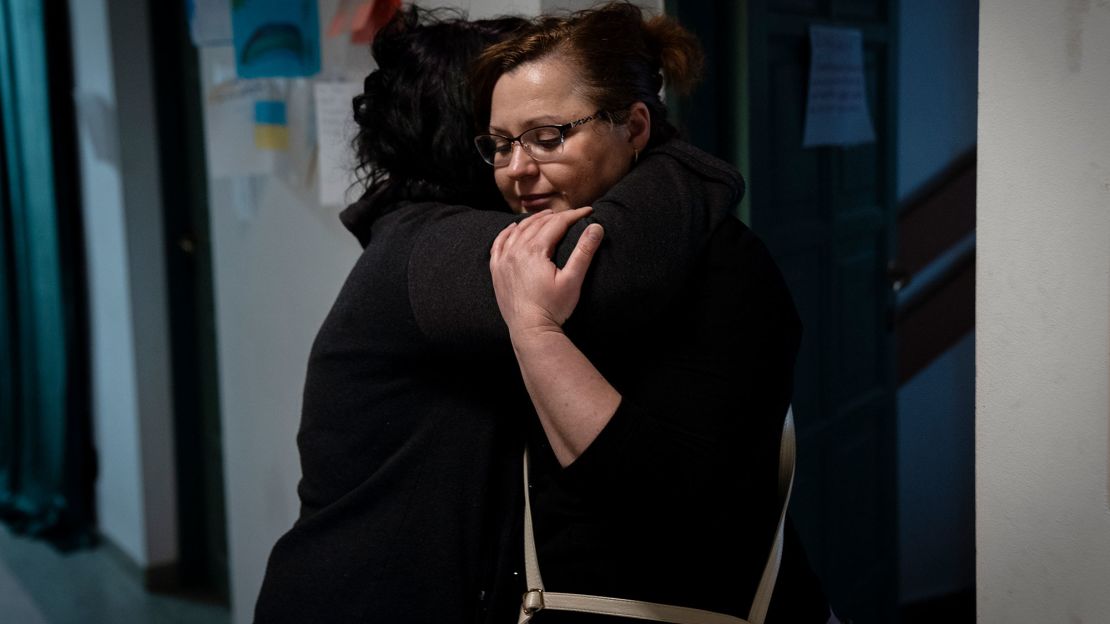

Turchyn turns and suddenly finds herself in her sister’s arms. There is a brief moment of joy, but no time to hug her mom. The smuggler wants to be paid now. He extorts her for more cash. She pays. At this point, there’s nothing more that she wants than to be with her family.

The exchange is finally over and the three women are reunited in Poland. They quietly and quickly embrace.

For the Ukrainians who now find themselves displaced in Russia, however, getting to safety is dangerous. Thousands of Ukrainian people have been forcibly deported into the country that has bombed and besieged them, Ukrainian authorities say. ?

When Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine began in late February, Turchyn, a Ukrainian-American medical student living in Cleveland, Ohio, frantically started searching through messaging apps, desperate to find any information on her hometown Izium, where her mom and sister lived.

“I was trying to find crumbs of information,” she explains. “We have these Viber (messaging app) groups, and everybody’s talking, ‘Do you know where a missile hit today? Do you know which house was destroyed today?’”

Her phone became inundated with images of the city, which has been at the center of fierce fighting for weeks. Food, water and medicine shortages have created a human catastrophe for the thousands living under constant airstrikes and shelling.

“Every day, it gets worse,” Max Strelnyk, a deputy in the Izium city council’s office, told CNN at the end of March. “There’s been no pause in the bombing – it started weeks ago – by the Russians. The dead are buried in the central park.”

Izium lies on the main road between Kharkiv and the Russian-backed separatist areas of Luhansk and Donetsk in eastern Ukraine, putting it in the crosshairs of Putin’s brutal onslaught.

A few days into the conflict, Turchyn lost contact with her family. Cell networks in Izium were deliberately cut or jammed. She feared her mom and sister had been killed.

“Somebody saw (on the messaging groups) that a missile actually hit my backyard, and I was crying so much because I didn’t know maybe, they are already dead,” she recalls through tears.

Unable to help her loved ones, Turchyn decided to help others and traveled to the Poland-Ukraine border, where millions of refugees were crossing into safety.?

“I came to Poland to take that energy and convert it into something,” she says. “Because crying and being depressed and just sitting at home – nothing was going to change.”

On Facebook, she found Lesko House, a disused office building turned into a refugee center by its owner Wojciech Bryndza, who spent thousands of dollars out-of-pocket to provide food and shelter to dozens of fleeing families.

Turchyn decided to live and volunteer at the shelter. Every day she would try to call her family.

Finally, she got a return call, but it didn’t come from Izium.

“I heard from them for the first time after a whole month, and I was so torn. I was happy they were alive. But I was terrified. They were in Russia. And I don’t know, should I be happy? Or should I be sad?” she says.

Turchyn later found out her mom and sister, desperate to flee Izium, had found a local resident willing to drive them to the Russian border for a price. There was no way to go east, further into Ukraine.

“We had only one chance to break out of this hell,” Vita, Turchyn’s older sister tells CNN. “And we decided not to lose this chance. We decided to go there and figure out what’s next later.”

Once they arrived in Moscow, the pair tried to board a train to Belarus, but say they were barred from doing so by Russian border officials.

Turchyn was desperate to get them out. She started to ask for help on the Viber groups that had provided her with information throughout the war.

“Somebody from Poland gave me a number, and that led to another number and another number,” she says of trying to find a smuggler online. “They try to keep it secret because obviously, it’s dangerous.”

Over the course of at least two days her mom and sister traveled in a large van with several other Ukrainians across Latvia and Lithuania, south towards Warsaw until they were reunited in Przemysl.

“Now they’ve filled me in on the details, it is worse than I thought,” Turchyn says as her mom and sister share details of their weeks under Russian bombardment.

“You can describe it in one word, it was hell. It was a nightmare you could never wake up from,” Luba, her mom, says.

Tens of thousands of Ukrainians living under Russian occupation face the same grim situation – cut-off from Ukraine even on their native soil, the only route out for the few who can find it is towards Putin.

Editor’s note: Last photo incorrectly identified the woman Mila is hugging as her sister. The caption has been corrected to identify her as an unnamed Ukrainian refugee and not her sister.