Amelia Cline can still remember what she loved about gymnastics; the 32-year-old Canadian says it was the chance to explore the limits of gravity.

“I was fearless,” she told CNN from her home in Vancouver. “Every child likes to learn how to flip, all of my early memories are pretty happy and joy-filled, which they should be.”

At the age of two, Cline says that her interest was obvious to her parents by the way she’d be pulling “little baby chin-ups,” at the kitchen counter.

Soon she had developed into a serious athlete. By the time she was nine or 10, Cline had outgrown her local coaches and was now travelling an hour from home to train at an elite club.

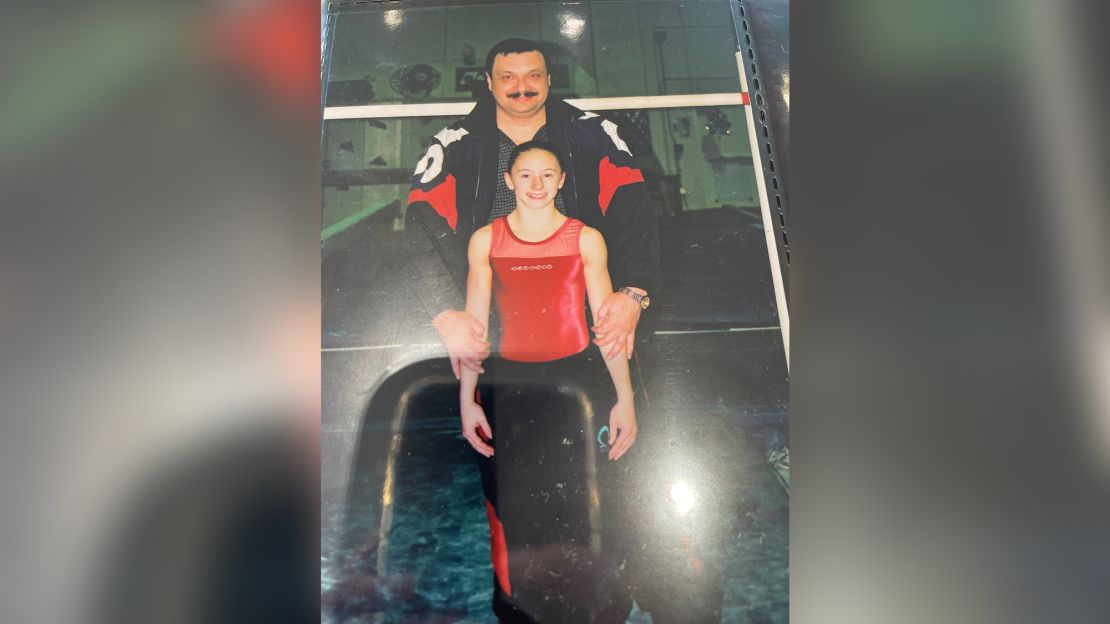

For a while, her love of the sport continued, but Cline says everything changed when Vladimir Lashin and his wife Svetlana arrived as the new coaching team. Cline says that the mood in the gym quickly darkened.

“Immediately, it was verbally abusive,” she recalled. “If you made any mistakes, they would scream and humiliate you. ‘This is rubbish, you’re rubbish,’ screamed at you over and over again.”

According to Cline, it wasn’t long before the coaches resorted to physical abuse, too.

“I was warming-up [for a standing split] and my hamstring felt really tight, and he got really annoyed.

“He said something along the lines of, ‘You’re just faking, trying to get out of doing this stretch,’ so he turned me around, grabbed my leg and forced it behind my ear.”

Cline can still recall the primal scream and the blinding pain, describing the sensation as “excruciating.”

“It snapped my hamstring completely and took part of my pelvis with it,” she adds.

As the alarm bells in her sensory receptors began to register the searing pain, Cline says that her coach offered no apology or remorse.

“He was angry, he screamed at me,” says Cline, adding that he accused her of lying and tried to distance himself from any responsibility for her shocking injury.

“There was no offer of medical treatment, no one called my parents. I think I ended up having to limp to the change room myself and call my parents to take me to the hospital,” she says.

CNN reached out to Cline’s former coaches, who it’s believed have left Canada.

Multiple requests for comment were sent via email and to their Facebook pages, but there has been no reply.

Barely a teenager, Cline became accustomed to a grueling schedule and painful injuries – she says she broke her hand in three places and tore a muscle in her spine that left her with a clot the size of a baseball.

Cline would attend school in the morning, then train from 1 p.m. until 6 p.m. before catching up on homework in the evening, often spending 30 hours a week in the gym.

She recalls that to give the appearance that her knees weren’t buckling on landing, which would result in a points deduction by the judges, the coach worked with her to permanently hyper-extend them.

With her feet on an elevated box and her legs raised from the floor, and she says Lashin would sit on her knees for several minutes at a time. She estimates that he weighed around 200 pounds.

‘Always being yelled at’

A few years later, Cassidy Jones (nee Janzen) arrived at the same gym.

She told CNN that she clearly recalls the culture of abuse which she says had become normalized and remembers Cline’s hamstring injury and that she was, “Always being yelled at.”

It wasn’t long before Jones also found herself in harm’s way. She described a back-handspring that she’d been struggling to master on the balance beam as a 10-year-old, and was told that one more failure would mean that she’d have to try it from an even greater height.

“I’m crying my eyes out and I’m scared,” she recalled. Jones reasoned that if she could position some padded mats under the beam, then she’d at least be able to minimize the risk, but her coaches overruled her.

“I tried, as a 10-year-old, to do the right thing and make myself safe.”

Shortly afterwards, her body twisted on the beam, resulting in three spiral fractures in her leg.

“I fell down and she told me to get up and do it again,” added Jones. “I couldn’t, obviously, because my bones were in half in multiple spots. They just left me there on the ground for about an hour, because they assumed I was faking. They told me to get out of the way so other people could use the beam.”

Jones says her body went into shock, “I had goosebumps, I was shivering and shaking, I was so cold.”

Eventually, her mom was called and she was driven to the hospital, her leg was put into a full-leg cast and she was in a wheelchair for months.

After about two weeks, the coaches called the family home. “Mom thought it was to check on me,” she said, “but it was to blame me, they were yelling at my mom on the phone, ‘She should have been able to do it, she hurt herself, it’s not our fault.’”

In 2011, Jones sued her coaches and received damages in a mediation settlement. She quit gymnastics shortly after the fall and considers herself fortunate to have escaped some of the torment that might have followed if she’d stuck with it much longer.

As a seven year-old, she says she was already following the unspoken code of the gym and trying to make herself vomit before the daily weighing sessions.

Fifteen years later, she says that she still has a recurring nightmare, a feeling that she’s arguing with her coach, Vladimir Lashin.

“It’s very out of character for me because I don’t raise my voice, I’m very self-controlled. I don’t know what we’re yelling about, but I’m yelling like crazy, and I can’t yell over him. I can’t yell loud enough.”

Forced stand on scales.

After her hamstring snapped, Cline told CNN that she was still expected to train for three to four hours a day.

Two months later, it was time for the national trials. On the eve of the event, Cline says Vladimir Lashin asked her to try a Yurchenko double pike – one of the most dangerous vaults in gymnastics.

Named after the Soviet gymnast Natalia Yurchenko, the move involves a blind backhand spring onto the vault – any kind of misstep can be catastrophic.

“I think I laughed,” she recalled, “I thought he was kidding because it was so absurd that he would even be expecting me to do this when I was still injured – I hadn’t been vaulting for weeks.”

Cline says she begged him to assist with the vault and he reluctantly spotted her. “Even that was almost a total disaster, I landed pretty much on my face,” she says.

Lashin then demanded she try it again, this time without assistance, according to Cline. She says she was terrified but didn’t feel as though she could refuse.

“It was disastrous, my feet didn’t hit the springboard properly, so I didn’t get enough momentum to get up onto the vault and I didn’t have enough momentum to make the rotation at the end,” adds Cline. “I landed on my neck.”

Since they were using competition mats, Cline says it was a big fall onto a relatively hard surface.

“I had to take stock of whether I could still move my limbs,” she continues. “Thankfully, I could, but then I realized that he was still screaming at me and telling me to do it again and again. There was no way I could say no to that request.”

Cline says her neck was in excruciating pain as she attempted what would be her last-ever vault in gymnastics.

“I completely missed one hand off the vault and landed on my head again. I was crying in the change room with ice on my neck when he demanded that I come back out onto the floor.

“Then he forcibly took me by the arm and dragged me into his office and forced me to stand on the scale. ‘This is why you can’t do it!’ He interrogated me about what Easter candy I had eaten.”

It was a final humiliation, but Cline says that while she was spinning through the air on her final, ill-fated vault, she had a moment of clarity and made the decision to quit the sport in the interests of her own self-preservation.

Her dreams of perhaps competing in the Olympics had been dashed and her gymnastics career was over. Replacing the sport that she had so loved would now be a lifetime of debilitating pain and psychological torment.

And she was still just 13 years old.

Over the last few years, the sport of gymnastics has lurched from one crisis to another. Hundreds of athletes accused the former USA Gymnastics national team doctor Larry Nassar of sexual abuse and their governing bodies of failing to protect them.

Following his guilty pleas on child pornography and a number of sexual assault charges in 2017, he will spend the rest of his life in prison. In a scandal dating back two decades, more than 368 athletes came forward to allege sexual abuse in gymnastics programs across the country.

Around the same time, other national teams were beginning to come to terms with their own abusive cultures.

In February 2021, Gymnastics New Zealand’s Chief Executive Tony Compier admitted that “emotional abuse, body shaming, physically abusive training practices, harassment and bullying,” had been uncovered by an independent review into the sport.

Two weeks later, a group-claim lawsuit alleged widespread physical and psychological abuse by British Gymnastics coaches on athletes as young as six years old.

The law firm representing them, Hausfeld, told CNN that they are working with 38 athletes, including four Olympians, and are in direct negotiation with British Gymnastics.

In May 2021, the Australian Human Rights Commission concluded that gymnastics in the country contributed to a “high-risk environment for abuse.”

The report found evidence of “bullying, harassment, abuse, neglect, racism, sexism and ableism,” enabled by a “win-at-all-costs approach, the young age of female gymnasts and inherent power imbalances; a culture of control; and an overarching tolerance of negative behavior.”

And in September last year, trainers in the Swiss national program resigned en masse after an ethics investigation upheld athletes’ complaints of psychological abuse and a series of poor performances.

Now, Canadian gymnastics is facing its own moment of reckoning.

Cline is the representative plaintiff in a class action lawsuit which has been filed against Gymnastics Canada and half a dozen provincial governing bodies, including Gymnastics BC, which would have overseen the gym in which Cline says she became so damaged.

Though not listed as defendants, both Vladimir and Svetlana Lashin are named in the lawsuit’s allegations, which details her vaulting injury incident and “almost daily … physical abuse … inextricably linked to a culture of psychological abuse” and “inappropriate physical contact.”

The lawsuit also says that “rather than face punishment for their abusive conduct, Vladimir and Svetlana were rewarded by both Gymnastics BC and Gymnastics Canada.”

Notably, according to the lawsuit, Vladimir was named as a coach for Team Canada at the 2004 Olympics in Athens and then promoted to National Coach/High Performance Director in Women’s Artistic Gymnastics in 2009.

According to the lawsuit a number of Canadian gymnasts have brought forward complaints “spanning decades,” alleging “sexual, physical and psychological abuse and institutional complicity that has enabled the culture of mistreatment … to persist.”

The suit is the first stage of a complicated legal process that could escalate exponentially in scale and take years to resolve.

“We really need these institutions to be held accountable for the systemic abuse that they’ve allowed to ensure for decades,” Cline explained to CNN.

“We’re trying to send a message that ‘you will not be able to allow these things to continue without being held liable for them.’”

The suit is also intent on providing compensation to the athletes who need intensive physical and psychological treatment and Cline has reason to believe that hundreds of former athletes could get involved.

In March, more than 400 male and female Canadian gymnasts put their names to an open letter which explained that fears of retribution had prevented them from speaking up about a ‘toxic culture and abusive practices’ within the sport.

In response, Gymnastics Canada said in a statement: “While we are saddened to learn that dozens of athletes feel that we failed to address these issues, we are committed to continuing to educate and advocate for system-wide reforms that will help ensure all participants feel respected, included and safe when training and competing in sport.”

Almost all say they have experienced physical and/or psychological abuse, but there are also survivors of sexual assault.

“We know there are many, many out there who have experienced sexual abuse,” said Cline. “Unfortunately, we know it’s a component and we know that it’s actually quite significant.”

After the lawsuit was filed on Wednesday, Gymnastics BC told CNN in statement: “The allegations we have been made aware of are very serious, and we take them as such.”

Gymnastics BC added that in early 2020 it had created a Safety Officer role “to educate our community on maintaining a Safe Sport environment for all” and that in June 2021, the organization had approved a new complaint management handbook.

In a statement sent to CNN on Thursday, Gymnastics Canada said while the organization had also not been served the suit it took the allegations “very seriously,” adding that it was “committed to providing a safe environment for members of our sport.”

Since going public with her story about her life as a young gymnast in a 2020 blog, Cline says she has been flooded with messages from athletes all over the country, whose stories echo her own.

She has also spoken with survivors from all over the world.

“If you put our stories side by side and you removed our names,” she said, “you wouldn’t be able to tell who’s who. We’ve got a very serious problem, not just within Canada, but within gymnastics generally.”

Cline believes that because the athletes are so young when they start training that they are incredibly vulnerable.

She spent more time with her coaches than with her parents, and she says the athletes were explicitly told not to share their experiences in the gym with her family at home as a culture of silence was encouraged.

“We were counselled on how to avoid talking to our parents about it, it was made very, very clear that we would be in significant trouble if we told our parents what was going on,” says Cline.

“If these things were happening in a school or at a home, there would be serious consequences almost immediately.

“But for some reason, when we put it in the context of a sport and particularly gymnastics, we normalize it to such a degree that we completely lose sight of the fact that this is child abuse. This is straight up child abuse.”

It’s almost 20 years since she walked away from the sport she had once loved, but Cline says she is still constantly tormented by it – both emotionally and physically.

There’s the debilitating back pain since the age of 14, the arthritis in her neck, she says she has nightmares and is constantly on the brink of an eating disorder.

“I don’t weigh myself,” she reveals, “I can never get on a scale. Even if I’m at the doctor, I ask them not to tell me the number. It has required constant vigilance to make sure that I’m not slipping into really harmful eating patterns.

“I’ve talked to dozens and dozens of girls and boys and they very much struggle in adulthood, whether it’s eating disorders or PTSD or depression or self-harm addiction.

“And, of course, the debilitating physical pain. This doesn’t just stop because someone has quit the sport, it’s something that’s going to continue to plague these people for the rest of their lives.”

Cline concedes that the sport of gymnastics will always present a risk of injury, but she believes that such injuries would be mitigated with healthy training methods.

And she certainly doesn’t think that the psychological trauma should be inherent to the sport. “Elite sport is hard,” she concludes, “But it shouldn’t ever produce things like eating disorders, self-harm and PTSD.”