When Dr. David Schonfeld’s daughter came home and told the story of a lockdown drill at school, she talked about making jokes with other students while her class hid in a closet for 30 minutes.

Schonfeld, a pediatrician and director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, was shocked to hear about the levity. It was just after 9/11, and he reminded his daughter, then a middle schooler, that such drills were serious and needed to be treated as such.

“‘Dad, I know it’s serious. That’s why I was joking,’” he recalled her telling him.

She then discussed the fear that permeated the closet and the rising sense of panic. The students knew it was a drill, but the thought of the worst-case scenario and the reality of why they were all there overtook them.

The massacre that killed 19 students and two teachers in a Uvalde, Texas, school this week shocked the nation, but these shootings are becoming more common, Schonfeld said. In addition to loss and stress from Covid-19, today’s kids are growing up with news about students being killed in schools and drills to prepare them for the possibility such violence could happen on their campus.

“Even if they weren’t in Texas, I think children are having more anxieties and worries related to school shootings,” clinical psychologist Robin Gurwitch said. “How do we best support students before, during and after?”

Children are often aware on some level of the violence happening around the country, said Gurwitch, a professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University Medical Center and senior adviser for the terrorism and disaster program of the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress Network. And even the best lockdown drills can stoke fear and anxiety in them, Schonfeld added.

They are faced with a threat to their assumptive world, or an event that reshapes the assumptions they make about the world from a young age, he said. They also can be subject to secondary stress, which can happen when the trauma they observe affects them, said Charles Figley, director of the Tulane University Traumatology Institute.

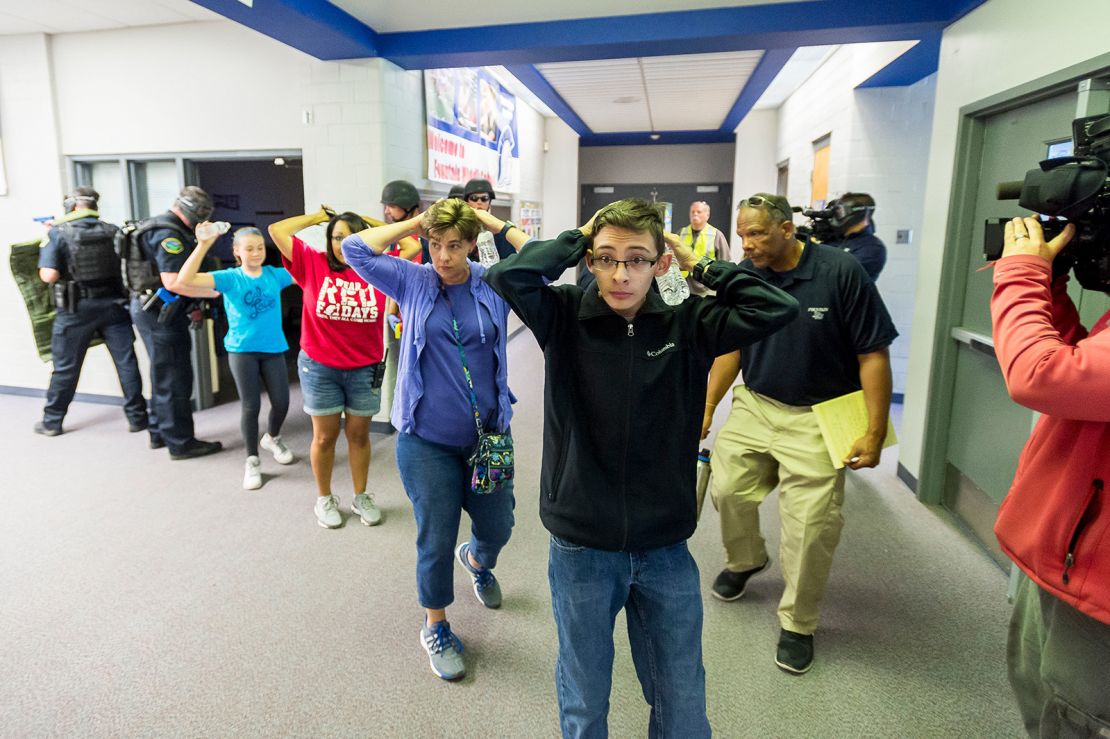

Lockdown drills are not always in preparation for an active shooter; they can be for any threat of danger, but they are not necessarily conducted the same across the country and can have a negative impact on students when done the wrong way, said Jaclyn Schildkraut, associate professor in the department of criminal justice at the State University of New York at Oswego, whose research focuses on school and mass shootings.

Not all drills are equal

There is some benefit to preparing for potential disaster, Schonfeld said.

We want to know some level of protocol is in place to maintain calm and as much safety as possible if there were a lockdown, just as if there were a fire, earthquake or tornado, he said.

But there are ways to conduct them that are better for students’ mental well-being, Schildkraut said.

Drills should not be a surprise. Ideally parents are made aware, and students will know that the procedure is a drill and that there isn’t a present danger, Gurwitch said.

“There can be some calmness in knowing that this is what I’m supposed to do,” she added. “I don’t think my school is going to catch on fire because we have a fire drill, but I know what to do should that happen.”

Drills should also never be sensationalized with fake blood and gunshots or people portraying perpetrators, Schonfeld said. Those exercises, called active shooter or high-intensity drills, don’t show a benefit to students and can be unnecessarily overwhelming, he said.

“We do not raise the temperature and put smoke in the hallway to simulate a real fire,” he said.

Schildkraut trains schools in drills and collects data about the impact they have on students. And preparation that teaches them how to seek safety can relieve some level of anxiety, she said.

Training can go too far, however, Schonfeld said. Preparation that tells children they should intervene in a violent situation can put them in an impossible situation and then leave them with feelings of guilt and shame in the aftermath of an actual attack, he added.

How we can help kids

Supporting kids through their fears about possible violence at school isn’t easy, but making an effort to do so can start simply, Gurwitch said.

First, adults have to begin a conversation. It can be hard to bring up scary topics, but avoiding them can make kids feel like they don’t have a place to go to ask questions – which is key to them feeling safer.

Kids of various ages likely have different levels of awareness, and it is important to take their developmental stage into account when talking about violence and lockdown drills, Gurwitch said. You can start by asking what they know already.

As caregivers, we want to give kids reassurance that nothing bad will ever happen to them but avoid doing so or minimizing their fears, Schonfeld said.

We can reassure them that the adults in their lives are doing everything they can to keep them safe and show them actions your family, school and community might be taking, Gurwitch added.

It is also important to share and model the coping skills you use, such as breathing, distraction, meditation and conversations with loved ones. Make sure your kids know that different things work for different people, but you are there to help them find out what works best for them.

Reports of violence and preparations for its possibility in a place students go almost every day can be stressful, and it’s not surprising these stoke feelings of fear, grief or anxiety. How those feelings manifest may not look the same for all kids – there can be headaches, behavior changes or school absences – so be sure to keep the conversation open and don’t be afraid to seek help from a mental health professional, said Figley of the Tulane institute.