When I left a Covid-ravaged Hong Kong, I was in search of a sanctuary.

It was early March and the city was in the throes of the biggest coronavirus outbreak per capita in the world.

Little could I have known as I boarded the plane that my cunning escape plan would take me from the frying pan into the fire; that as I landed in Shanghai I would be swapping the world’s biggest outbreak for the “world’s strictest lockdown” – and 70 days of enforced confinement.

Still less could I have foreseen that, after serving three weeks of government-mandated quarantine on arrival, my housing compound would be hermetically sealed for a further 49 days straight, or that my mom and I would catch Covid, or that I would be carted off for a further spell of isolation at one of the government’s notorious “fangcang” camps.

And if you’d told me then that it would be under the glaring strip lights of one of those “fangcang” camps, amid the whiff of dubious makeshift toilets and the dirty laundry of thousands of strangers, that I would have an epiphany about the joys of communal living and the mental health benefits of enforced breaks, well … then I probably wouldn’t have believed you.

But let me back up and explain.

At the time I boarded the plane, the siren song of Shanghai – my hometown – seemed hard to resist.

In Hong Kong, Omicron was running amok, but in Shanghai cases were still in the single digits and with China’s iron-fisted approach to infections it seemed reasonable to think things would stay that way.

That was my first mistake.

Keep calm and quarantine

During my three-week quarantine on arrival, I watched in horror as the cases exploded.

And the longer I stayed inside, the higher the cases climbed.

By the time I was finally allowed out, I had one fleeting day of freedom then was forced back inside for a lockdown that would supposedly last just four days.

Nothing to worry about, I thought.

That was my second mistake.

In fact, the residential compound where I was staying with my parents was about to be sealed off for the best part of two months as the virus worked its way through its 21 stories and 300 inhabitants.

Covid could seemingly pass between the floors and walls and the realization even the strongest measures couldn’t stop it was terrifying and shocking. Each time a single person tested positive, the lockdown was extended another 14 days.

Many of us responded by becoming model Chinese citizens, volunteering to disinfect the estate and help distribute food and essential goods – all of which had to be delivered – directly to people’s doors.

And the volunteers sanitized with a vengeance, lugging around 30-kilogram (66-pound) tubs of chemicals and donning full hazmat suits to douse in disinfectant every incoming package, every nook and cranny.

By the time they had finished, the building was so awash with chemicals that some of my neighbors’ touchscreen electronic door locks had corroded and stopped working.

This might have helped ease people’s nerves, but there’s little evidence it did anything to stop the virus spreading.

Twenty-four days into the lockdown, my mom — who like my dad and I had not set foot outside the apartment except for a mandatory test – saw the dreaded double line in her daily self-administered antigen test.

I waved goodbye to mom as the government workers hauled her off to one of the 288 schools that had been converted into isolation sites. The next day, I found I too had been infected.

Welcome to the jungle

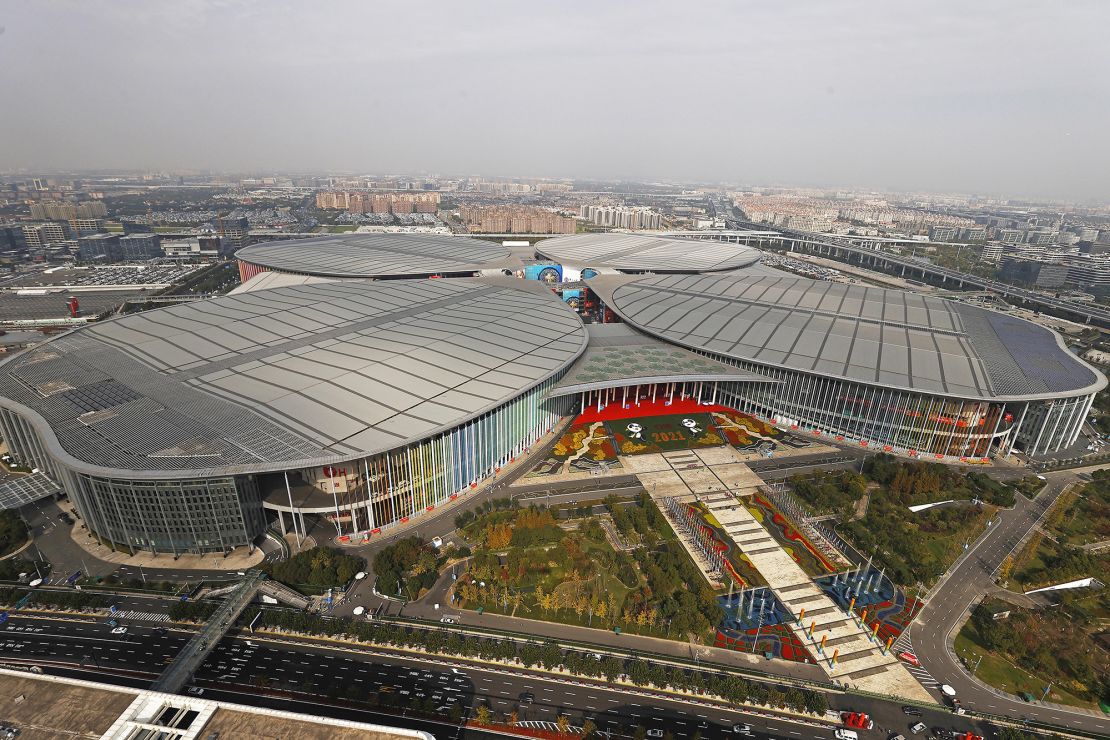

Any hopes of seeing mom again were soon dashed as people were randomly assigned to different sites. I was bused to the National Exhibition and Conference Center, Shanghai’s largest quarantine facility – nicknamed the “lucky clover” due to its shape.

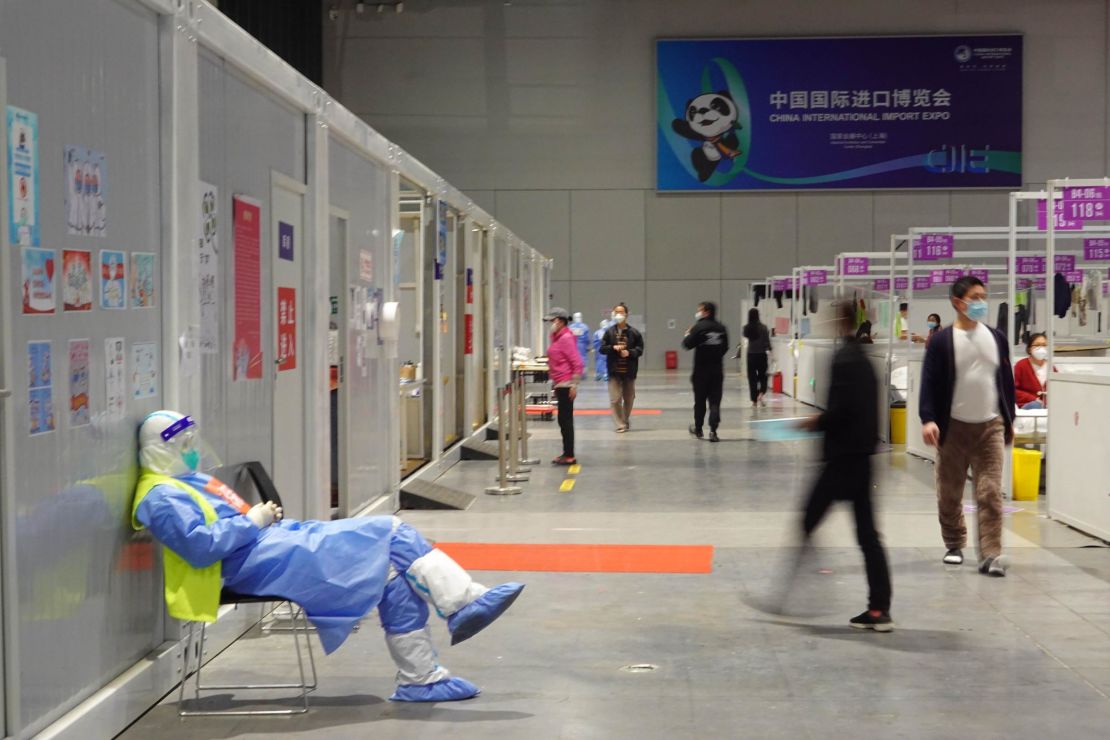

Once host to the world’s biggest auto show, it was converted into a makeshift Covid hospital with 50,000 beds, one of many public venues to have been repurposed into what Chinese refer to as “fangcang”.

Fangcang date back to the original Covid outbreak in Wuhan and are widely viewed by Chinese as a success story.

Somehow though, my arrival felt less than auspicious.

The second I stepped into my designated hall – one half of a leaf of the four-leaf “lucky clover” – I was overwhelmed.

A sea of what looked like oversized baby cots and laundry hanging from the rafters stretched before my eyes.

“Welcome to the jungle,” I thought, as hoards of strangers dressed in their pajamas hustled and bustled around me, made all the scarier by my mental state, which had deteriorated from a lack of social interaction.

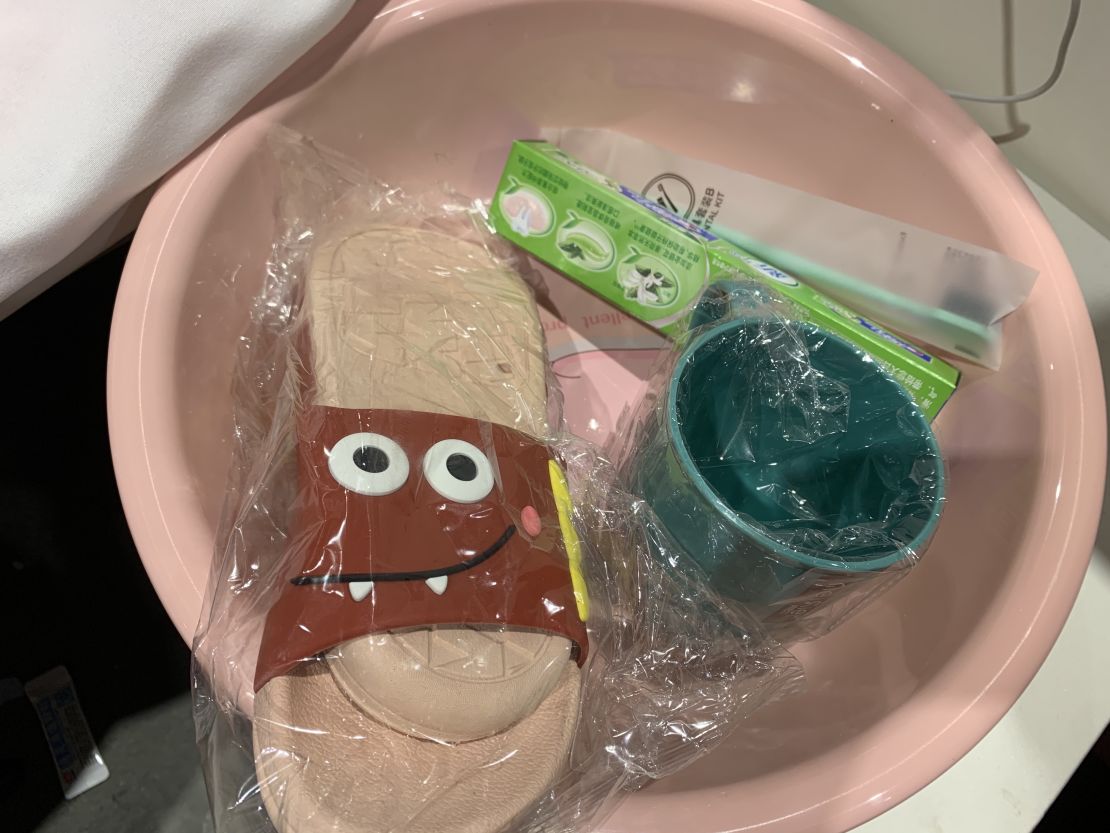

A nurse assigned me a cot, the previous occupant of which had kindly left behind a large yellow bag marked “medical waste.” Then I was handed a bag of my own, containing bedding, a plastic basin and a cup for washing, a toothbrush, toothpaste, towel and slippers.

It was only later that I discovered the true horror lurking behind the “lucky clover”: the toilets.

Do you feel lucky?

It is hard to describe the odor that results from thousands of people depending on dozens of portable squat toilets day after day.

Let’s just say that every visit to the washroom – a shady, stinking area covered by a giant tent on the edge of the clover – was a test of courage.

The constant booming of the plumbing system lent every visit a sinister feel. When you approached there would be long, snaking queues of people with tissue paper wrapped around their hands, all gingerly inspecting toilet cabin after cabin in doomed attempts to find one that might be hygienically acceptable.

It wasn’t the cleaning staff’s fault – simply the volume of people. The toilets would soil and the tissue bins fill and overflow far sooner than the staff could get to them.

The floor was always wet, which made balancing while squatting harder – especially as the cabin locks rarely worked, meaning one hand needed to be dedicated to fending off unwanted intruders.

Unfortunately, given the many gallons of water I was forcing down my throat in an effort to flush out the virus, I spent far more time here than I would have liked.

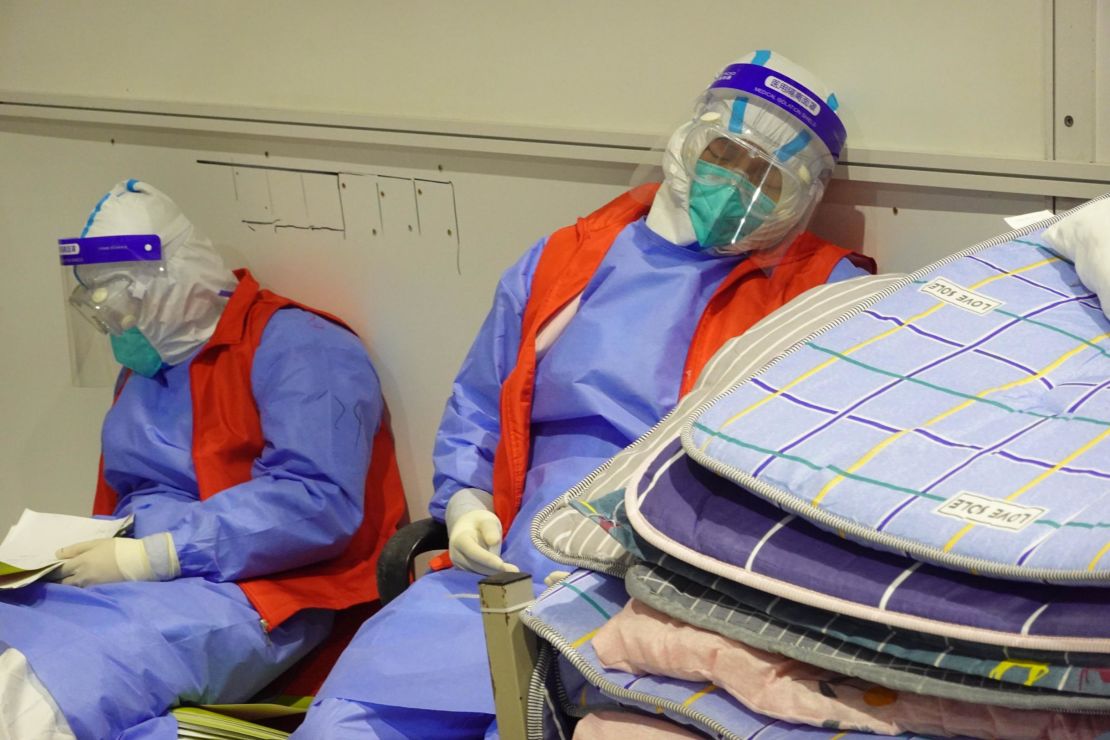

Then there was the problem of trying to sleep in a place where there is no darkness. Rows of ceiling lights stayed on throughout the night, so I took to wearing two face masks – one for my mouth and nose and one for my eyes.

Others struggled with the noise; the sound of thousands of people snoring, grinding their teeth, tossing and turning and groaning and grunting in their sleep gave this the feel of a safari.

That first night, it took me hours to fall asleep, only to be woken what felt like moments later by a loudspeaker blasting “please come take the PCR test” – at 6:00 am.

The lack of sleep was making things seem weird, but things were about to get weirder still.

Seeing the light

I was in an enormous room with 3,000 strangers, and I felt all alone. All I had was a tiny cot, a corner, a cabinet and a stool. The intense overhead lights left me feeling sterile, cold and exposed. It felt like a hospital, a bazaar and a maze all rolled into one.

That’s when something deep inside me stirred: memories of the communal living experiences I’d had as a child growing up in China.

As part of the state curriculum, city kids like me had been sent to countryside camps to learn how to farm and work on assembly lines. Part of the experience was sleeping on large, undivided platforms with little privacy. The living conditions were poor, but any discomfort was outweighed by the youthful excitement of having a sleepover with classmates.

My feelings of awkwardness in the “lucky clover” fell away. What I once viewed as embarrassingly intimate now felt like a pajama party.

Most people were just minding their own business, and something not entirely unlike “normal life” was continuing. People lounged on their cots, making calls with friends and family, scrolling on their phones and laughing at TikTok-style videos.

Even those separated from their loved ones did their best to stay positive. One couple across from my cot would video-call the 12-year-old daughter they had been forced to leave at home, alone. The mom would take her through meal-prep; the dad fielded math homework questions; and when she sobbed, they would comfort her.

But the brightest spot was the food. It was no feast, but having access to filling meals seemed fortuitous during such a strange time.

Normally, people from Shanghai are spoiled by the city’s vibrant food scene, but I was keenly aware that during this time of lockdown many people outside the “lucky clover” were genuinely scared of starving.

Within the clover, there was no need to scramble for groceries or make do with what came your way.

Breakfast meant congee, baozi (steamed buns), eggs and pickles. Lunch and dinner were hot, and even more generous – usually two main dishes with a choice of protein – shrimp and beef, chicken and pork, fish and chicken – and three sides of vegetables. Special menus were available for Muslims, diabetics and vegetarians.

Meals were rarely repeated and neither were the encouraging fortune-cookie style messages attached to the boxes.

“Go Shanghai!”, “Zero worries, endless happiness….” and “Life is always warm and bright. A stumble will be followed by further progress” were among my favorites.

I shared photos of my meals on social media, with many friends saying they wished they would get Covid just for the free food. They might have been joking, but I often saw people hoarding snacks – milk and fruit – and taking the goodies home when they finally left.

I soon realized, too, that for some of those around me, staying in the “lucky clover’ really was a piece of good fortune, a reprieve from the hectic non-stop hustle of a city of 25 million.

That’s when I met Mr. Sun.

He was a worker with a state-owned construction company who had ended up staying in the same fangcang that just weeks previously he had worked to repurpose. He told me that since March his job had felt like fighting a war as he and his fellow workers had been tasked with building fancang after fancang, day after day.

The nonstop work had left his shoulder buckled and hands calloused. Buried in work and toiling away he had lost track of time and was almost “relieved” to hear he had caught Covid.

“I could finally take a break,” he said.

‘Everyone will be scared of me’

Much as I tried, like Mr. Sun, to look on the bright side, it was hard to fully banish my mental anxiety.

My routine had become monotonous, I missed home, and felt icky from not having showered for days.

It was like I was trapped in a maze, barred from leaving despite feeling fine. Even at their height, my symptoms were only mild – fatigue and occasional coughing and sneezing – and that was a blessing as the little medical assistance that was on offer was largely pointless. Nurses were too busy to check on us and the most you could hope for were basic remedies like paracetamol, cough syrup, sleeping pills and traditional Chinese medicine.

Alas, there was no cure for Covid, or stubborn PCR test results. Days after my symptoms had disappeared I, like many others, would continue to test positive and remain stuck in limbo.

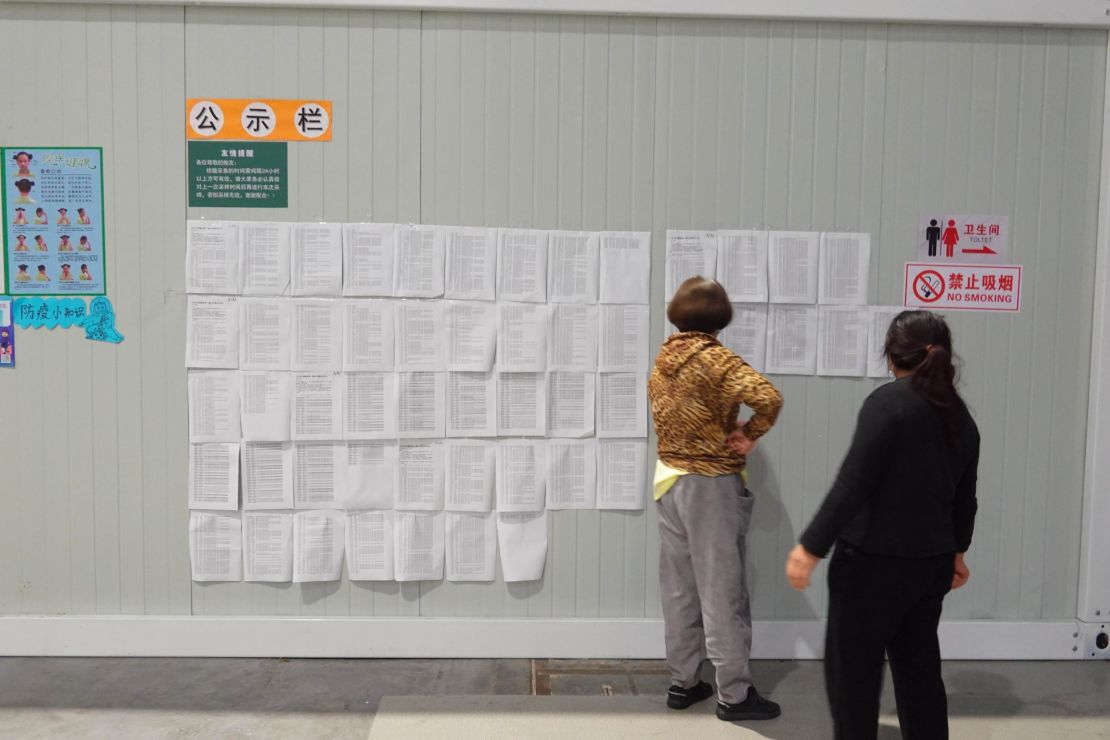

The release of the PCR test results was itself a scene every day.

Everyone’s name and results would be printed out and posted on a wall – much like how Chinese schools publicly release exam scores – and every day the large crowd poring over them would be a smorgasbord of emotions from joy and despair.

I learned that PCR tests are not black and white. At least five people I knew had their hopes of freedom dashed as their results oscillated between positive and negative.

Desperate to avoid the same fate, I would thoroughly rinse my nasal passage and throat with a saline solution before taking my daily test.

Whether it was the saline or fate, I tested negative on my seventh day – and after a follow-up test 24 hours later I was told to prepare for discharge.

Mr. Sun, the constructor worker, was told the same. But while I was excited, he seemed peaceful and contemplative. He told me he was concerned his neighbors might not allow him back in his compound. “I’m someone who tested positive. Everyone will be scared of me,” he said.

I tried to console him, saying the infection would have strengthened his immune system and he would be less likely to fall ill again. He smiled reluctantly and said he hoped the community would be equally understanding.

The next day, Mr. Sun was missing from the line of people to be discharged. The nurse couldn’t find him anywhere. I don’t know if he decided to stay or not.

Maybe what was a prison for many was actually a sanctuary for him.

Editor’s Note: On leaving the camp, the author was able to secure a rare flight back to Hong Kong, departing Shanghai on May 20. Despite efforts beginning June 1 to “reopen” the city, life in Shanghai remains heavily restricted, with an increasing number of neighborhoods being placed back into full lockdown