Editor’s Note: Carine and Ana?se Kanimba are the adopted daughters of Paul Rusesabagina, the hotel manager who inspired the film “Hotel Rwanda.” The views expressed in this commentary are their own. View more opinion on CNN.

Our father, Paul Rusesabagina, is a hero.

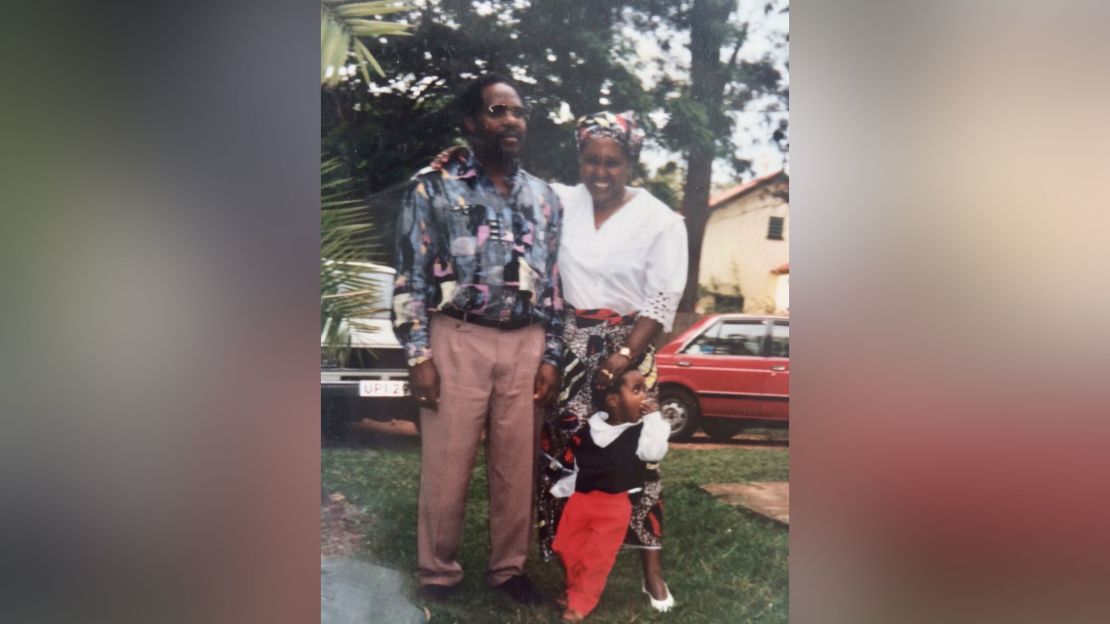

He rescued us from a refugee camp in Rwanda after our biological parents were killed during the 1994 genocide and raised us as his own. We – Carine, who was one at the time, and Ana?se who was two – were saved in addition to the 1,268 lives he saved by protecting inside a hotel for the duration of the genocide.

His story was told in the Oscar-nominated film “Hotel Rwanda,” and he received numerous awards for his bravery and humanitarian work.

Over the years he became one of the most high-profile critics of Rwanda’s longtime President Paul Kagame. Then, in August 2020, our father – now a Belgian citizen and US permanent resident – was kidnapped by the Rwandan government and has since been in jail on false charges for over 650 days.

Now as representative heads of state, including the Prince of Wales, descend on Rwanda for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) Monday, they must not turn a blind eye to the host nation’s human rights violations.

While it is sad that the CHOGM is being held this year in a country that does not adhere to the Commonwealth’s core values and principles, we must see this as an opportunity to shine a light on Rwanda’s lack of democracy.

Our family is asking Prince Charles not to remain silent to this reality and to not shake the hand of the tyrant who is holding our father as a political prisoner.

The United Nations, the Clooney Foundation for Justice, the International Bar Association and many others have stated publicly that our father is only in prison because he spoke out against a government that does not accept any criticism.

The United States recently classified our father as a “wrongful detainee,” noting the massive irregularities in his capture and trial.

Rwanda has no freedom of speech, a central value of the Commonwealth of nations and a right my father has been imprisoned for exercising. There is also no democracy, freedom of association or right to take part in opposition political parties in Rwanda.

Kagame “won” two elections with over 98% of the vote in 2017 and 93% in 2010 and is able to run for office for decades to come following changes to the Constitution in a controversial 2015 referendum. Critics are regularly harassed, brutalized, tortured, imprisoned, exiled, or have disappeared or died in suspicious circumstances.

This includes both political opponents and former members of the regime who are seen as potential threats. Rwanda is a government that rules only for Kagame and a small elite.

Our father is also one of many victims of Rwanda’s practice of transnational repression, a tactic typically used by Russia, China and Iran, where a government reaches across borders to silence critics. In addition to my father’s case, Rwandan officials and agents harass and intimidate opponents in other countries, including the US, United Kingdom and Europe.

Our father was kidnapped almost two years ago, lured from our home in San Antonio, Texas, through Dubai, where he was tricked into boarding a flight to Kigali. An agent of the Rwandan Government, posing as a Bishop, asked our father to come to Burundi and speak to church groups about reconciliation. Having boarded a plane in Dubai expecting to fly to Burundi, he was drugged, waking only to realize he had landed in Kigali, Rwanda – a place to which he would never voluntarily return.

On arrival he was tortured for four days and forced to make a false confession, which was then used as “evidence” against him. He had no access to counsel of his choosing. He was forced to endure solitary confinement for 250 days, in violation of the UN’s Nelson Mandela rules, which characterize imprisonment of over 15 days in solitary confinement as torture.

And he was subjected to what international monitors agree is a sham trial, with no credible evidence presented that he was involved in any way in the terrorism-related crimes of which he was accused.

The Rwandan government has rejected all criticism of these processes, incredibly claiming that it has acted in a manner consistent with international law.

Even more heartbreaking, is that governments like the UK continue to partner with the Rwandan regime, including in the scheme to offshore vulnerable asylum seekers to Rwanda. It is unsurprising that the British government’s willingness to turn a blind eye to Rwanda’s widespread human rights abuses is garnering huge opposition from the church, civil societies, and all those who care about the plight of those fleeing for a better life.

Now our father has been sentenced to 25 years imprisonment, which will be a life sentence for a man who last week turned 68. Our only wish for his birthday is to bring him home safe to us. He is a cancer survivor with hypertension whose health is deteriorating while he is incarcerated. His current symptoms, including a weak right arm and facial paralysis, indicate that he may have had one or more strokes already while in prison, but these go untreated.

While it is still incomprehensible to us, and so many victims of the Rwandan regime around the world, that Rwanda was given the privilege of hosting the CHOGM this year, its presence in Kigali also offers a unique opportunity.

The Prince of Wales and other CHOGM leaders can choose to focus on their shared values and principles and push those members who do not uphold those values in practice to do so. This includes Kagame’s Rwanda. Although Prince Charles is not a political figure, he can seek dialogue behind closed doors, or even ask to visit our father.

Rwanda has many friends in the CHOGM, both countries and individuals, and we urge the Prince of Wales and all of the other leaders assembled not to stay silent and to ask Kagame to provide our father with a compassionate release now, before it is too late.

Our father saved us in 1994. We plead with the international community to take this opportunity to save him.