Thursday night, both Sens. Mitch McConnell and Chuck Schumer had reason to celebrate. After decades of inaction on gun legislation, the two men were able to achieve something that neither had imagined possible just weeks before: a compromise on gun safety legislation brokered by four members they’d each given their blessing to negotiate.

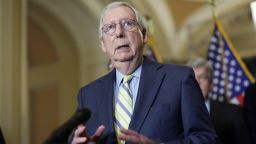

For McConnell, the effort on guns was an opportunity to make changes to school security and mental health, which he viewed as the root of the problem, and shore up some support for suburban voters Republicans had suffered losses with in the last election.

It was a rare move for McConnell to announce support for bipartisan talks that would likely divide his Republican conference just months before the midterms, but McConnell acknowledged Thursday in a call with reporters that he also saw a political upside to engaging in the talks.

“It is no secret that we have lost ground in suburban areas,” McConnell said. “We pretty much own rural and small town America, and I think this is a sensible solution to the problem before us, which is school safety and mental health and, yes, I hope it will be viewed favorably by voters in the suburbs we need to regain in order to hopefully be a majority next year.”

For Schumer, the vote Thursday night was the culmination of an early decision to hold off on a partisan show vote in hopes – no matter how slight they were – that he could see a bipartisan gun safety bill pass under his leadership as majority leader.

A group is formed

Not long after the shooting in Uvalde, Texas, Democratic Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona stopped and intentionally gaggled with the Washington press corps.

Frustrated by inaction on gun safety legislation in the wake of previous tragedies, she wanted to make it clear this time had to be different. That night she approached McConnell of Kentucky and GOP Whip John Thune of South Dakota and asked them whom she could negotiate with.

“They said (Republican Sens.) John Cornyn and Thom Tillis. I texted both men right away,” she said, referring to the senators from Texas and North Carolina. “We agreed to meet the following day.”

Thirty minutes later, she got a text from Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut, who had been working for a decade to reform the country’s gun laws ever since the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in his own state.

“Are you serious? Would you like to work on this?” she remembers him asking.

“Thirty minutes later,” Sinema said, “He and I were meeting in my hideaway.”

What developed over the next month was an unexpected and even odd pairing of lawmakers: Sinema, a Democrat who had bucked her party on gutting the filibuster and tax policy, Murphy, a Democrat who had devoted his career to calling for sweeping changes in gun policy like an assault weapons ban and universal background checks, and Cornyn and Tillis, two conservative senators who rarely voted for proposals that didn’t have the backing of a majority of their party.

But the group was able to get something done that had bedeviled Washington negotiators so many times after shootings like Sandy Hook, Pulse, Las Vegas and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, cementing their reputations as effective negotiators that fellow senators referred to as the “core four.”

The following is based on CNN interviews with more than a dozen members of Congress and staff, many on background in order to speak more freely to get the inside account and never-before-seen details on how the Senate gun deal came together after more than 30 years of gridlock.

The core negotiating group was from disparate political backgrounds, but somehow – over a rolling text chain, hours of meetings in hideaways and staff negotiations – were able to forge a narrow agreement on gun safety legislation that had been elusive in the Senate for three decades. Aides and members credited the result with their temperaments, agreement to leave certain hot-button issues off the negotiating table, blessings from their respective leaders and President Joe Biden’s willingness to let the Senate work its will.

“The Democrats this time seemed to be willing to get an outcome on what we considered on our side the problem which was school safety and mental health, and were willing to give up on their wish list of things that we felt … infringed on Second Amendment rights of US citizens,” McConnell said in a call with reporters.

While the legislation is far from the panacea that Democrats had campaigned on or hoped for, the bill represents significant changes in the country’s gun laws and challenged the thesis that the National Rifle Association had somehow become too powerful for any Republican to ever buck.

“At the end of the day, we are the members of the Senate who have to make a decision, and I have to answer to 10 million people, and they all live in North Carolina,” Tillis told CNN in an interview Thursday. “Groups are important; it’s not that I don’t respect them. I respect the (National Rifle Association), I respect (the National Shooting Sports Foundation). I respect National Right to Life and Susan B. Anthony and a number of other conservative organizations, and I’ll be continuing to advocate for them, but on this particular issue we just have to agree to disagree.”

Leadership gives their blessing

Hours after the shooting in Uvalde, Schumer was under tremendous pressure to act quickly on gun legislation. He took a procedural step that would allow him to move on a House-passed gun bill that faced no chance of passage in the Senate, but at the very least would send a signal that Democrats were taking action. This, he said publicly, would become an issue that voters would have to decide at the polls if Washington wouldn’t solve it.

The next day, the majority leader held an early morning call with his staff to walk through the options. Devastated by the massacre, the New York Democrat and his staff concluded that holding a vote so quickly on a House bill destined to fail would only further divide Republicans and Democrats on gun policy, a source familiar with the conversation told CNN.

Instead, Schumer wanted to entertain another option. After giving his opening remarks on the Senate floor, Schumer called Murphy. Minutes later the two men were seated face to face in his office. The chances of a deal, Murphy had told Schumer, were slim. But, Murphy wanted to try. With a few caveats, Schumer wanted to let him.

The plan, according to a source familiar, was to see where the talks could go, but to insist they wouldn’t go on forever. If meetings ceased being regular or progress screeched to a halt, Schumer was prepared to pull the plug, bring the House-passed background check bill to the floor and force the issue with voters in the midterms.

One day later, McConnell came out with his own endorsement of the talks. In an exclusive interview with CNN, McConnell said he’d talked to Cornyn that morning after the Texas senator had returned from Uvalde and had “encouraged him to talk with Sen. Murphy and Sen. Sinema and others who are interested in trying to get an outcome that is directly related to the problem.”

In the weeks that followed, Cornyn and Tillis kept the minority leader constantly apprised of their progress with Tillis telling CNN that McConnell’s approach was largely to trust the two senators – both on the Senate Judiciary Committee – to cut a deal that would be palpable to a large number of members in the conference.

“He never had a discussion about specific provisions,” Tillis said of McConnell’s role in the process. “His [message] was if you get to a framework that we believe we can get members’ support, I want to look at it, and then I’ll make a decision about it. … There were no specific instructions from him on priorities.”

For his part, Cornyn also communicated sometimes directly with Schumer, at times when the two men would see each other for early workouts in the Senate gym, according to a source familiar.

The senators also fielded calls from colleagues offering a host of ideas and proposals they wanted to include in gun safety legislation. One of those ideas came from Sen. Susan Collins, a Republican from Maine, who had wanted to include a provision she had with Democratic Sen. Martin Heinrich of New Mexico that created a new federal statute against straw purchasing. Another idea for mental health provisions came from Sen. Roy Blunt, a retiring Republican senator from Missouri, and Democratic Sen. Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, who had been working for years to provide more federal funding to mental health clinics around the country.

The conversations about the bill were also happening with people outside of Capitol Hill. A source familiar told CNN that from the beginning, Republican negotiators were regularly engaged with gun groups like the National Rifle Association and the National Shooting Sports Foundation, fielding questions and concerns about what may end up in the bill. McConnell, too, said he was engaged in those talks.

“Senator Cornyn and I and others discussed the issues in the bill with the NRA. These were fruitful discussions, but in the end they decided not to support it,” McConnell said.

Winning the GOP votes

From the very beginning, there were more Republicans engaged in the discussions on a gun safety bill than there had been in decades, a sign Murphy took as promising.

“The sheer number of people we had talking was different than any time before,” Murphy said. “We had 12 members who were sitting down and talking about guns. Then, the composition of the small group was really unique. The four of us have never worked on another issue before, we may not work together again after spending four long weeks together.”

Some GOP senators were clamoring to include their provisions in the bill. Some Republicans were deeply skeptical of touching anything that dealt with the Second Amendment, but many felt that something was fundamentally changing about the way voters viewed gun rights in America.

“This is an issue that people around the country are talking about,” Sen. Lisa Murkowski, a Republican from Alaska, said in early June as the talks were heating up. “They are certainly talking about it in my state and rightly and appropriately so. We are gun owners, we are proud Second Amendment supporters, but we are also moms, grandmothers and have kids in school so we care about what is going on.”

The thinking within the group of four negotiators was that in order to keep members bought in, communication was key.

“They communicated constantly with members about what they were doing and why they were doing it,” one GOP senator, who wanted to speak on background to freely discuss the talks, told CNN. “I was convinced early on we needed to do something.”

The group wanted to prove the votes would be there before the bill was even rolled out, a strategy to protect any agreement from the ire of the NRA. They decided the framework with 10 Republican backers was the earliest opportunity to do that.

“What we were determined to show from the start (was) that we had the votes,” Murphy said. “What was most important was the framework. Having 10 Republicans and 10 Democrats. Once you know something is going to pass it makes it easier to join.”

Behind the scenes, a source familiar with the talks said Tillis and Sinema were engaged in trying to shore up the GOP votes needed to demonstrate they could actually pass the bill. It was those two – the sources said – who ultimately were able to get 10 GOP votes to be 15.

McConnell and Cornyn, meanwhile, commissioned a poll of 1,000 gun owners to test various provisions that ended up going in the framework and to show the conference that many of the provisions had broad GOP support. Cornyn walked members through those number during a private Republican lunch.

It also helped, multiple sources said, that Republicans weren’t getting pressure from the bully pulpit in an election year. Aside from a primetime address where Biden spoke in support of a series of gun proposals he’d like to see, the President offered his encouragement largely behind the scenes to Murphy. Murphy says he was in almost daily communication with White House staff and talked to the President on a number of occasions, but that he leaned on Biden as a sounding board, asking for advice at times on how to be an effective negotiator in a body where Biden operated effectively for decades, rather than calling on the President to use his office to pressure Republicans into being a yes.

“He wanted updates. We had to make sure that we were writing something the President would sign,” Murphy said. But he added Biden “was offering encouragement and advice.”

“He has cut more deals in the Senate than I could ever imagine,” Murphy said. “He is a good sounding board when you are trying to do this kind of agreement.”

The last sticking points

Despite steady progress, the group of four lawmakers got stuck on two key issues in the final days of their talks: how to close the so-called boyfriend loophole in a way that could still win the support of Republicans and how to deal with so-called red flag laws.

Democrats wanted to use federal funding incentives to encourage states to pass laws that would allow an individual or law enforcement to petition a court to take away the guns of individuals who were deemed a danger to themselves or others. But, the issue had struck a chord with many Republicans. Red flag laws had attracted the ire of the NRA and had become a key concern for conservatives in the conference who were on the fence about backing the gun safety bill. Republicans’ preference was to ensure the federal dollars could go to both states that had red flag laws and states that had other crisis intervention programs like drug courts, mental health courts or veterans courts.

The core four senators told CNN that the group had relatively few moments of real tension given the topic they were negotiating. Sinema, as is her usual style, had brought libations in the form of wine to many of the meetings to help keep members on track, and senators had largely grown to have trust in each other and their staff that everyone there wanted an actual outcome.

But, the Thursday before the bill text was rolled out had proven to be a frustrating day for at least one member of the group: Cornyn. Negotiators were haggling over very technical language, sources told CNN. And the talks, according to Cornyn’s comments that day, had been going in circles.

Cornyn had a flight back to Texas to catch, and he warned it was time to make some decisions.

“I’m frustrated,” he told reporters after hours of meetings that day. “I am not as optimistic right now.”

Recalling that day, Cornyn wouldn’t call it a turning point, but he did say it had proven to be an important moment when he actually departed – a bit frustrated – for the airport.

“I am not the world’s most patient guy. Some of my colleagues around here like to have meetings, more meetings and more meetings. I hate that, so I really was asking everybody to make a decision because we knew that we didn’t have limitless time,” Cornyn said. “I literally had to catch a plane – that was the main reason – but I also think maybe the thought process was this thing could fall apart if people get impatient and so maybe that helped give people a greater sense of urgency.”

In the end, senators were able to bring the deal back from the brink throughout the weekend. And just a few days later, they not only rolled out legislative text, but won 14 GOP votes on a procedural vote for the bill on the floor.