Editor’s Note: J. Peter Scoblic is a senior fellow in the International Security Program at New America and the author of “U.S. vs. Them,” a history of American nuclear strategy. David R. Mandel is a cognitive psychologist affiliated with the Department of Psychology at York University. The views expressed in this commentary are their own. View more opinion on CNN.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four months ago, a question that keeps popping up in conversation with colleagues – and with relatives, from Washington to Paris – is: Should they get out of town before the nuclear missiles start flying?

In reality, there’s no way to outrun a strategic nuclear war, which would kill untold millions, destroy the economy and poison the planet.

But there’s no doubt the fears are real. In March, an Associated Press poll found that three-quarters of Americans worry that Russia will use nuclear weapons against the United States, and over half worry that the Russians would target their hometown specifically.

Likewise, a report the following month from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found that 69% of Americans fear a US nuclear exchange with Russia.

On the one hand, this reaction seems alarmist. After all, the cold logic of nuclear deterrence still applies. Mutual assured destruction remains mutual and assured. On the other hand, Putin’s nuclear saber-rattling is scary. Indeed, from the first day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine he warned that any outside interference would lead to “consequences as you have never experienced in your history.”

Meanwhile, Russia’s ambassador to the US raised tensions when he complained: “The current generation of NATO politicians clearly does not take the nuclear threat seriously.” Perhaps to make sure they did, Russian TV recently showed an animation in which a 100-megaton nuclear torpedo turned Britain “into a radioactive desert.”

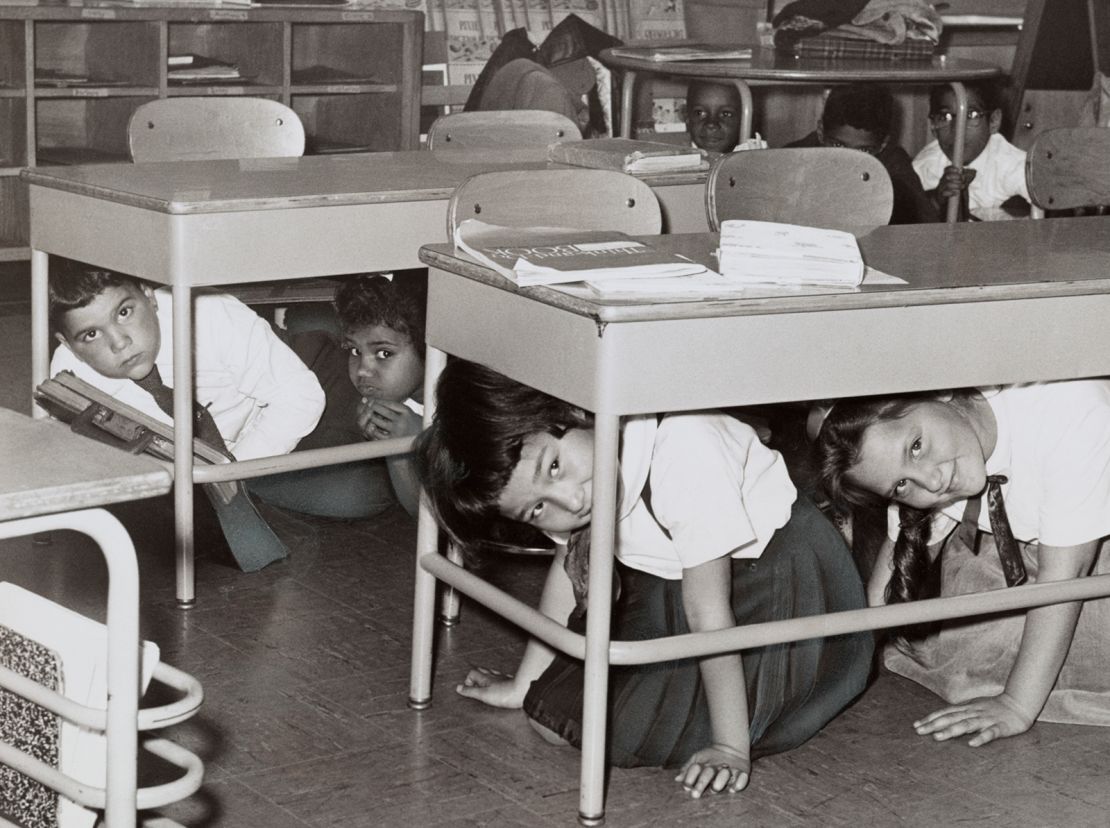

For those of us who grew up in the shadow of the Cold War, the resulting fear is all too familiar, reviving memories we thought were safe to jettison. The threat from nuclear weapons did not dissolve with the Soviet Union, but the existential terror they spawned did.

Over the years, mass demonstrations calling for nuclear disarmament faded, images of Armageddon ceased to drive pop culture and artifacts that once stirred dread came to seem like campy relics of another age. (Today, you can buy a “Fallout Shelter Nuclear Retro Vintage Look Rusted Reproduction Metal Sign” for less than $20 on eBay.) If public expressions of fear were any indicator, the danger no longer existed.

Now, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has revived those fears – and those fears have been officially sanctioned by everyone from the CIA to the European Union and beyond. As UN Secretary General António Guterres told reporters in March, “The prospect of nuclear conflict… is now back within the realm of possibility.”

That sounds bad, but the realm of possibility is a vast place. So, what is the probability the war in Ukraine will turn nuclear?

Answering that question might seem impossible. But the truth is a bit more heartening. Scientific studies – many of which, such as the Good Judgment Project’s discovery of “superforecaster” traits, emerged from a tournament funded by the US intelligence community – have shown that it is possible to put meaningful probabilities on geopolitical events, even those that seem like they ought to be unpredictable.

Such forecasts are probabilistic, meaning we can never say whether they are “right” or “wrong” (unless someone says there’s a zero or 100% chance of something happening, leaving absolutely no chance for alternative outcomes). Which raises a reasonable question: How do probabilities really help?

On a personal level, estimating probabilities can help us make sense of situations that are so complex as to be baffling. When faced with an overwhelming situation – such as the threat of a nuclear war – disaggregating the problem into its constituent parts is a useful strategy. For a nuclear war to break out, certain events would have to happen. If we can assign probabilities to those events, we can unravel the giant mass of atomic anxiety. We can put a name – or in this case a number – to our fear and reckon with that worry, putting it into perspective along with other sources of anxiety.

This process helps policymakers as well. Once we have laid out the different paths to war, we can better identify key decision points and the degree of risk they pose. In doing so, we can make sure our actions do not inadvertently increase the chance of apocalypse. We can also prioritize dangers, more rationally allocating resources, like time, attention and money – and see where we’ve gone wrong, or where we might go wrong.

Admittedly, assigning a meaningful probability to nuclear war presents a particular challenge because a nuclear war has never been fought. Good forecasters often begin to assess odds by calculating the “base rate,” the relative frequency with which events take place, but in this case the base rate is zero.

Yet the risk of nuclear war is obviously not zero. The US and the Soviet Union came close to nuclear war several times during the Cold War, the most famous example being the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. So, where to begin in 2022?

It is highly unlikely that Russia would launch nuclear weapons at NATO countries unless NATO troops had first joined the fight in Ukraine. The conventional would precede the nuclear. There has been much speculation that Putin is “irrational,” by which people tend to mean that he did something that was, in hindsight, not in his self-interest.

However, there is little evidence to suggest that Putin is suicidal, and there is a great deal of evidence to suggest that the US would respond in kind if hit with a “bolt from the blue” attack, guaranteeing Russia’s destruction. And as Putin once said, “What use to us is a world without Russia?”

So, it makes more sense to start by asking about the odds of NATO troops getting into a shooting war with Russian forces. During the Cold War and in the decades since, Washington and Moscow have managed to avoid armed confrontation almost entirely. They fought proxy wars and armed each other’s adversaries, but direct combat has been the exception not the rule, as in 2018 when US troops battled Russian mercenaries in Syria.

Given the low historical incidence of combat and, more importantly, President Joe Biden’s vow not to deploy American troops to Ukraine, we could reasonably argue that the odds of conventional war are low but not zero. We cannot know what the true probability is, but we can make an educated guess and say that it is “highly unlikely,” a term that NATO defines as being between 0% and 10%. The midpoint of that range – 5% – gives us a reasonable starting place.

Let’s say that we live in a universe in which Russian and NATO forces do fight – that we find ourselves in that 5%. What, then, are the odds that the conflict would turn nuclear? Many analysts have warned that, in the face of military defeat, Putin might use a so-called “tactical” nuclear weapon on the Ukraine battlefield – much as NATO planned to use tactical nuclear weapons during the Cold War if the larger Red Army swept through the Fulda Gap into West Germany, as was long feared.

Thankfully, it never came to that, but almost four decades later, the situation is reversed, whereby NATO is conventionally stronger than Russia. So, Russia might well resort to nuclear weapons in a conflict if it felt that its existence was threatened, as it might if NATO troops approached the Russia-Ukraine border.

The risk of nuclear miscalculation or accident is also higher during a crisis than during calmer times. Again, we cannot know the true probability that Russia would use nuclear weapons, but if we are very concerned, we can simply assume the worst – or nearly the worst – and estimate there is a 95% chance that Russia would use tactical nuclear weapons in a fight with NATO forces.

At this point, the question would turn to one of the most fraught topics in nuclear strategy: whether escalation can be controlled. Can we confine a nuclear war to the Ukrainian battlefield, or will it inevitably spread to encompass strategic targets in NATO countries themselves? Given that we have little theory and virtually no data to go on, humility suggests that we treat this question as one of maximum uncertainty – a 50/50 chance it goes either way. That is, we are acknowledging our ignorance and factoring it into our overall estimate.

This seems like a gloomy view of the future, but if the probabilities are conditioned on one another – that is, if we use the numbers above and calculate the odds of NATO troops directly fighting Russian troops and Russia using nuclear weapons in response and the conflict escalating to a strategic exchange – we find that the odds of a nuclear strike against NATO cities are about 2.4% (i.e., 5% x 95% x 50%). We can then gut-check this estimate against those of nuclear experts and well-calibrated forecasters.

One group of highly regarded forecasters put the probability of Russia using a nuclear weapon against London before February 2023 at 0.8%. The “superforecasters” at Good Judgment put the chance of Russia using any nuclear weapon outside its territory before August 5 at 2%. And Harvard professor Graham Allison, author of a classic study of the Cuban Missile Crisis, puts the odds of Russia striking US cities between 0.1% and 1%.

While these estimates vary roughly over an order of magnitude – in part because they address different geographic areas and different time frames – they all fall within the boundary of what Western intelligence agencies deem the lowest probability level (as noted, NATO calls anything between a 0% and a 10% chance “highly unlikely.”)

Again, we will never know the true probability. But we have established a reasonable way of deconstructing the problem that embraces epistemic caution given the lack of historical data. This logic suggests that the odds of a nuclear strike on a NATO city are currently small.

Does this mean we can relax? It does not. One irony of low probabilities is that they can flip unwarranted anxiety to unwarranted apathy even for high-consequence contingencies. The way people treat low probabilities is problematic: As a cognitive simplification strategy, our minds tend to round very small probabilities down to zero (e.g., turning 2.4% into 0%).

The good news in our thought experiment is that the key turning point on the road to nuclear war is solidly within the West’s control: NATO leaders are the ones who decide whether their troops will directly confront Russia’s.

We think the probability of them doing so is low, but if the US and its allies do commit troops to the fight in Ukraine, they should recognize that they might spur Putin to climb the escalatory ladder. In other words, they might well be handing him greater power over what happens next, when we want the opposite.

In the short term, then, our efforts to prevent nuclear disaster must focus on maintaining as much control of the situation as possible. In the longer-term, we should pursue the predictability, transparency and stability that a robust arms control framework can provide. Relying solely on an unregulated balance of terror is terrifying.