The US Supreme Court ended its most explosive term in decades this week deeply split along ideological lines, surfacing two different visions of America and the Constitution.

The nine justices, in the cases that most captured the country’s attention, mirrored the rest of the nation at a perilous moment as they issued opinions with irreconcilable views on reproductive health, religion, gun rights and the environment.

As news of the decisions swept through the states, the reaction was predictable. Red states rejoiced, especially in the area of abortion, as some raced to ban or further restrict the procedure. Blue states, on the other hand, set out to digest stunning new implications that will change the way Americans live.

For their part, liberals believe that the court’s majority, made possibly by Donald Trump’s presidency, is rewriting the rules, decimating precedent and destabilizing the court.

Conservatives, on the other hand, believe the justices in the majority are correcting the course of constitutional jurisprudence. They realized a 50-year dream to upend what had been a constitutional right to abortion, while also bolstering a right to keep and bear arms for the first time in a decade.

“The competing sides have entirely different visions of the law and of American society generally,” said Daniel Epps, a professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis.

He said that the conservative wing of the court “looks backwards to what it sees as history and tradition.”

Meanwhile, Epps added, “the liberal wing is sounding the alarm about what the conservatives’ project means for the future and how it represents a radical change, not a restoration of the past.”

Caught in the middle is the country and court as an institution. It is lost on no one that the building itself – the marble palace – is currently crouched behind high security fences and closed to the public.

Abortion politics

The divide between the two sides was the starkest when the court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the majority, said that the court went astray in 1973 when it recognized a federal constitutional right to abortion in a landmark opinion.

“Roe was egregiously wrong from the start,” he said in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. “Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences.”

For Alito, Roe and the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision never solved any questions, they only “enflamed debate and deepened division.” He emphasized that “no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional protection” and that the decision belongs in the political sphere.

Liberals, however, see the issue from an entirely different prism, starting with women’s rights.

“One result of today’s decision is certain,” the three liberal justices wrote together in a rare joint dissent, “the curtailment of women’s rights, and of their status as free and equal citizens.”

Now that Dobbs is on the books, the dissenters said a state can transform “what, when freely undertaken, is a wonder into what, when forced, may be a nightmare.”

Central to their thinking was that the Constitution will no longer provide a shield despite its “guarantees of liberty and equality for all.”

While conservatives see no right in the Constitution, liberals counter that it is grounded in the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of liberty. The liberal justices said that the framers of the Constitution “understood that the world changes” and that rights could be defined “in general terms, to permit future evolution in their scope and meaning.”

For conservatives such as Carrie Severino, president of the Judicial Crisis Network, a group that supported Trump’s nominees, liberals are the ones guilty of not following precedent in other areas, including the Second Amendment.

“The left has always tried to create a different set of rules for cases involving abortion, and this is just another,” she told CNN

A week after the opinion published, abortion care was banned or severely restricted in a dozen states, according the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit that tracks abortion laws across the country and supports abortion access. Five states, including Alabama, Arkansas , Missouri, Oklahoma and South Dakota, enforced total bans. Others state began enforcing six-week bans – barring the procedure before most women even know they are pregnant.

Liberal-leaning states are working to secure funds to protect clinics, as well as help fund travel and lodging for women coming in from states hostile to abortion.

On Friday, Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy of New Jersey signed into law two bills protecting out-of-state residents seeking reproductive services and reproductive health care providers. The laws will shield health care providers from other state’s inquiries and prohibit the extradition of any woman who comes to New Jersey seeking legal abortion services.

The measures will “explicitly protect the rights of out-of-state women to an abortion in New Jersey,” Murphy said Friday.

Second Amendment and gun rights

The Second Amendment was implicated in New York State Rifle & Pistol v. Bruen, when the Supreme Court struck down a New York gun law enacted more than a century ago that placed restrictions on carrying a concealed handgun outside the home.

For years, Justice Clarence Thomas and other conservatives had urged the court to expand gun rights – accusing lower courts of thumbing their noses at the constitutional right to bear arms.

It was Thomas who wrote for the 6-3 majority in Bruen. Not only did he strike the New York law but he set out a new standard by which courts should evaluate other gun laws, marking the widest expansion of gun rights in a decade.

Thomas said that, going forward, the government “may not simply posit that the regulation promotes an important interest.” Rather, he said, the government must demonstrate that the regulation “is consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.”

In a scholarly opinion, Thomas spent several pages taking what he called a “long journey through Anglo American history of public carry” to conclude that New York had failed to meet its burden to identify an American tradition that would justify the state’s law.

The opinion will directly affect a handful of states with laws similar to New York’s law. Already, New York is moving to modify its permitting scheme while also imposing stricter training requirements and expanding a list of sensitive places where guns are prohibited, said Andrew Willinger, the executive director of the Center for Firearms Law at Duke.

Speaking at a news conference in Albany, New York, on Friday, Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul said, “The Supreme Court decisions were certainly setbacks, but we view them as only temporary setbacks because I refuse, as I’ve said from day one, I refuse to surrender my right as governor to protect New Yorkers from gun violence or any other form of harm.”

But because Thomas articulated a new standard for courts to use when considering gun laws, states with tough gun regulations are likely to see an array of new challenges from individuals emboldened by Thomas’ opinion.

“Going forward, we can expect challenges to gun regulations across the board,” Willinger said, “particularly in states with regulations that do not have a clear support in the historical record.”

Justice Stephen Breyer, writing for his liberal colleagues, seemed mystified by Thomas’s approach. Over several angry pages, he wondered why the majority would tell lower courts that they could put less emphasis, when considering gun laws, on a state’s justification for a law.

“The primary difference between the Court’s view and mine is that I believe the Amendment allows States to take account of the serious problems posed by gun violence,” he said.

To illustrate his point, Breyer dedicated a substantial part of his opinion to the issue of gun violence. He noted that 45,222 Americans were killed by firearms in 2020 and that since the start of the year there have been 277 reported mass shootings.

For his part, Alito, who had joined the majority opinion, wrote separately to criticize Breyer’s reference to mass shootings.

Again, the two sides seemed to be talking about different cases.

While liberals stressed an aim to regulate guns to diminish gun violence, Alito was concerned with people who wanted a gun to protect themselves.

He wrote about those who “reasonably believe that unless they can brandish or, if necessary, use a handgun in the case of attack, they may be murdered, raped or suffer some other serious injury.”

Church and state

In two religious liberty cases, the two sides were once again at odds, splitting along ideological lines.

In Kennedy v. Bremerton, the court ruled 6-3 in favor of a public high school football coach, Joe Kennedy, who wanted to pray at the 50-yard line after games. The school district suspended him, fearful that it would look like the school was favoring religion in violation of the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.

The conservatives saw the case as discrimination against free exercise and free speech; the liberals saw it as the entanglement of state with religion.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the opinion siding with Kennedy, holding that he had First Amendment rights to pray and that the Establishment Clause does not require the government “to single out private religious speech for special disfavor.”

The liberals struck back, expressing concern that students at the school would feel coerced to participate. Justice Sonia Sotomayor said that the court’s majority had broken new ground “paying almost exclusive attention” to the Free Exercise Clause’s protection of religious exercise, while giving “short shrift” to the Establishment’s Clause’s prohibition on state establishment of religion.

Sotomayor said the majority decision does a “disservice to schools” as well as the nation’s “longstanding commitment” to the separation of church and state. She called it a “perilous path in forcing States to entangle themselves with religion.”

In another case penned by Chief Justice John Roberts, a 6-3 court said that Maine cannot exclude religious schools from a tuition assistance program that allows parents to use vouchers to send their children to public or private schools.

“The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools – so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion,” he said.

Breyer took the wheel for the liberals, rejecting the notion that the case was about discrimination. For Breyer, who retired Thursday after nearly 30 years on the bench, it was about the need for government to stay out of the business of funding religion. Neutrality is necessary, he argued, by the fact that the United States has 330 million people who ascribe to over 100 different religions.

Breyer said that the Establishment Clause that bars the government from endorsing religion and the Free Exercise Clause that protects the practice of religion can work together. “The Religion Clauses give Maine the right to honor that neutrality by choosing not to fund religious schools as part of its public school tuition program,” he said.

Environment and climate change

On the last day of the term, the court again split along ideological lines in an important environmental case. A 6-3 majority curbed the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to broadly regulate carbon emissions from existing power plants

The opinion capped off a furious battle between states that believe the EPA has broad authority to regulate under the Clean Air Act and those who say that authority is limited.

The dispute began back in 2015, when the Obama administration announced its “Clean Power Plan” aimed at combating climate change.

It was immediately challenged by dozens of parties, including 27 opposing states, and it never went into effect. When Trump came into office, his EPA passed the “Affordable Clean Energy” rule, which drew a challenge from others, including blue states. When the DC circuit court froze that plan, West Virginia led other red states to the Supreme Court.

At the Supreme Court, again, the red states won.

For Roberts, it boiled down to an agency’s authority. He said that while a move to cap carbon dioxide emissions at a level that will force a nationwide transition away from the use of coal to generate electricity “may be a sensible solution to the crisis of the day,” Congress had not given the EPA such broad authority.

“A decision of such magnitude and consequence rests with Congress itself,” Roberts said.

Justice Elena Kagan, characteristically blunt, dedicated much of her dissent not to agency power, but to the problems in the environment. If the current rate of emissions continues, children born this year could live to see parts of the Eastern seaboard swallowed by the ocean,” she said.

In her view, Congress had given its blessing, and she found the majority’s focus on an agency’s authority “frightening.”

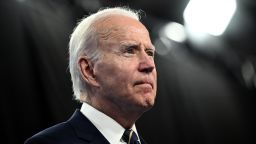

President Joe Biden called the decision “devastating” and said the opinion would take the country “backwards” while damaging the “nation’s ability to keep our air clean and combat climate change.”

The American public is split politically but overall is not thrilled with the court. Gallup released a poll showing that only 1 in 4 Americans have a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the high court. That is a record low, down 11 percentage points from last year.

“The beliefs espoused by the conservative majority of the court are not just different from but in fact are diametrically opposed to those of at least half the country,” said Jessica Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School.

“And thus while a large part of the country may view the court as out of step with their views,” Levinson said, “another swath of the country feels they finally have a court that reflects their views.”