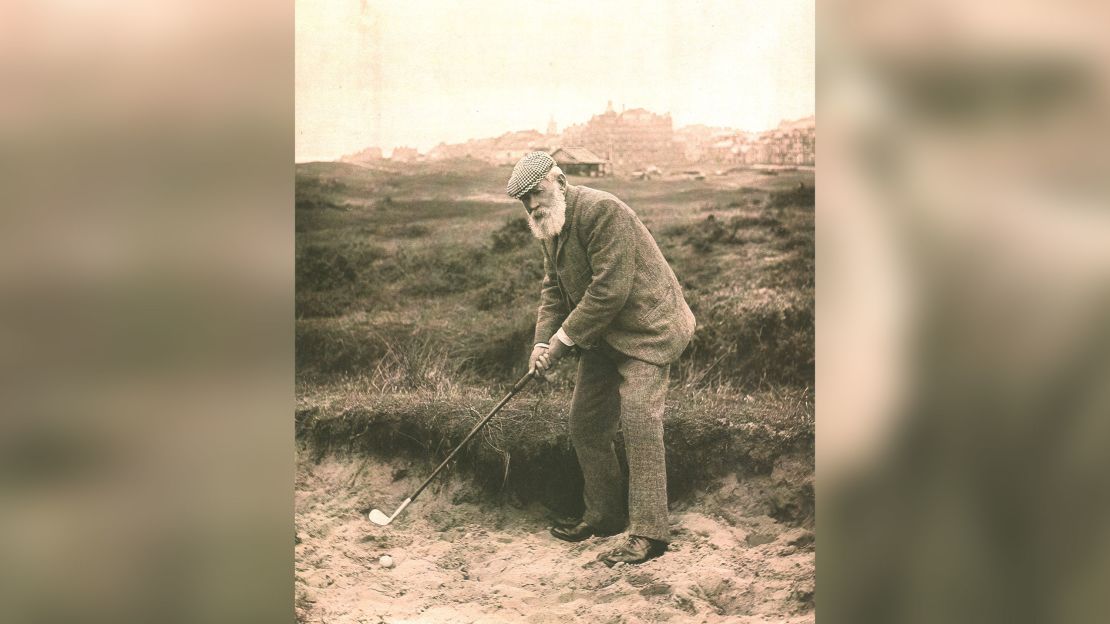

Golf has come a long way since Willie Park Senior and Old Tom Morris, in a field of just eight players, competed in the first Open in 1860 at Prestwick.

Long gone are the days of men playing in suits and using wooden clubs in a sport that has since transitioned into a multi-billion-dollar business.

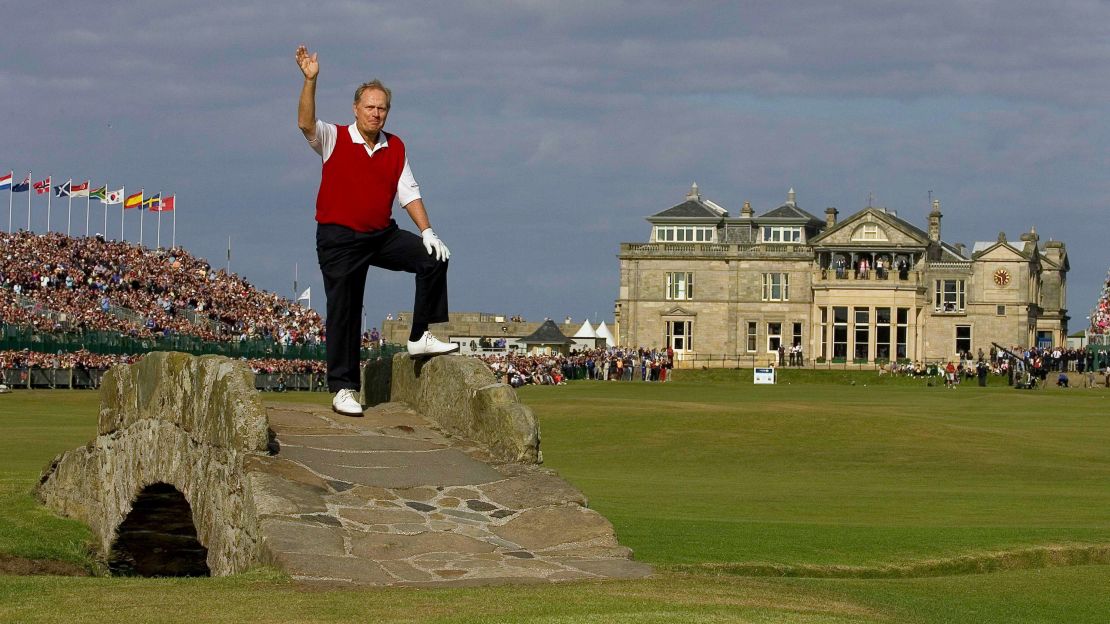

However, as the sport’s oldest tournament travels to the ‘home of golf’ – St. Andrews, Scotland – for its 150th edition, the traditional foundations face their biggest threat for over half a century.

The birth of the LIV Golf invitational series has rocked the sport, dividing players, organizers and fans about who is wrong, who is right and what the future of the sport should be.

The juxtaposition between the most historic and famous golf tournament being played on its oldest course with this new threat in the background, especially with LIV golfers playing in groups alongside their critics in Scotland, has led to the prospect of a fascinating major.

Breakaway

Not since 1968 has the PGA Tour faced a bigger structural threat than the LIV Golf series.

Although the official formation of the tour was in the 1920s, the modern-day organization that we now recognize came together at the end of 1968 after a group of players broke away from the PGA of America about a pay dispute.

Since then, it has blossomed into the primary driving force in golf, putting on the biggest tournaments around the world outside of the four majors.

Not only has prize money steadily increased, but – alongside the DP World Tour (formerly the European Tour) – the PGA Tour has also made great strides in increasing opportunity in golf, a previously closed-door sport.

Despite this, breakaway golfers who have joined the LIV Golf tour have cited issues with the current set up, and commissioner Jay Monahan’s unwillingness to listen to what they think would improve the PGA Tour, as reasons for joining the lucrative Saudi-backed tour.

LIV golfers will earn considerably more for playing in far fewer tournaments. As multiple major winner Phil Mickelson said, being able to maintain a work-life balance was a key reason for him joining.

Such reasoning has led to rebuttals from some PGA Tour players, including arguably the game’s most famous player, Tiger Woods.

“I disagree with it [the players’ decision to join LIV Golf],” the 15-time major winner said on Tuesday. “I think that what they’ve done is they’ve turned their back on what has allowed them to get to this position.”

Seven-time PGA Tour winner Billy Horschel succinctly dissected some of the complaints raised by LIV Golf players, saying earlier this month that those players who had left had “made their bed.”

“They decided to go play on that tour and they should go play there. They shouldn’t be coming back over to the DP World Tour or the PGA Tour,” Horschel said.

“To say that they wanted to also support this tour, whether DP or PGA Tour going forward, while playing LIV Tour, is completely asinine. Those guys made their bed. They say that’s what they want to do, so just leave us alone.”

Horschel said Monahan and the rest of the PGA Tour staff worked “tirelessly” so that the players could “reap financial rewards” and that criticism of the tour was also a criticism of its members, the players themselves. He conceded some players were “more upset than others.”

He added: “I’m not seeing my family for five weeks, but that is what my wife and I decided. Am I crying about it? No. I’m living my dream of trying to play golf professionally and support my family financially.”

Questions

The LIV Golf series has certainly made waves.

The tour, which is backed by Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) – a sovereign wealth fund chaired by Mohammed bin Salman, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia – has promised to offer players the chance to play fewer events for a vast increase in prize money.

However, the source of the money and players’ decisions to abandon the established golf tours have resulted in criticism from many,

Players have been accused of actively participating in Saudi Arabia’s regime of sportswashing, a term used to describe corrupt or authoritarian regimes using sport and sports events to whitewash their image internationally.

Saudi Arabia has been accused of using sportswashing in recent years to divert attention from the country’s dismal human rights record.

Bin Salman was named in a US intelligence report as being responsible for approving the operation that led to the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, though he has denied involvement. Human rights groups have also criticized the country for conducting mass executions and for its treatment of gay people.

Players have been pressed by journalists regularly about the morality of taking money from such a source. During his press conference ahead of last month’s first LIV Golf event, Mickelson repeatedly stated: “I don’t condone human rights violations at all.”

For some, the backlash has taken a toll.

“I can’t turn on my Instagram or Twitter account without someone telling me to go die,” Graeme McDowell said earlier this month. “I just wish I had said nothing. I wish I had sat there and shook my head and said, ‘No comment,’ but it’s not who I am.”

These were not considerations that Willie Park Senior and Old Tom Morris had to contemplate back in 1860. The days of players being able to solely focus on their sport and avoid answering tricky questions are long gone.

Similar to football players signing for Saudi Arabia-backed Newcastle United or Qatar-backed Paris St-Germain, golfers joining LIV Golf will have to field questions about human rights and sportswashing.

But both factions will be traveling to Scotland to tee off for the Open on Thursday with high hopes.

Against the backdrop of history and the greats that have come before them, this modern battle will take place between the rebels and the conformists, between the new and the established. It could be the beginning of a new era.