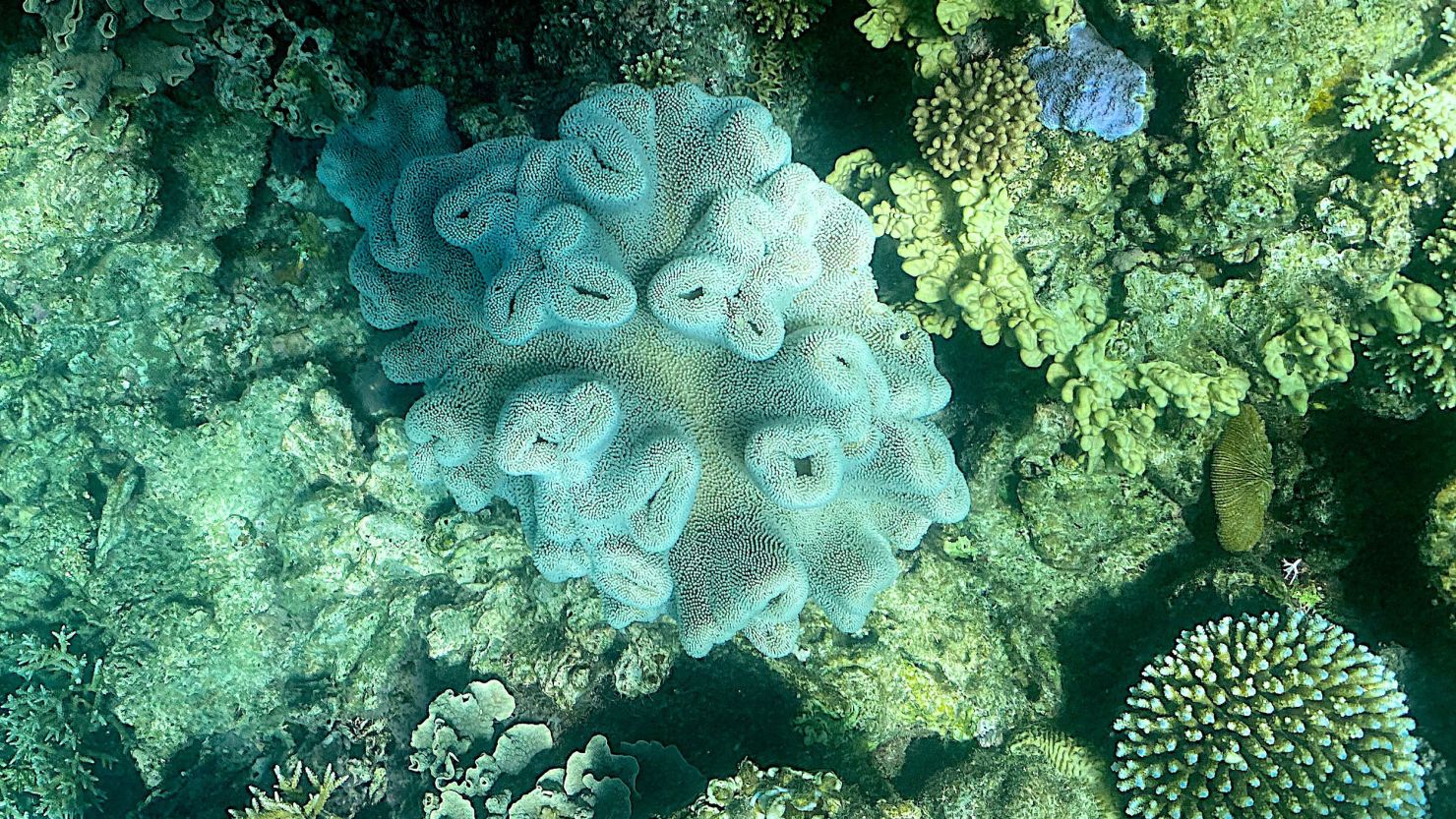

Parts of the Great Barrier Reef have recorded their highest amount of coral cover since the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) began monitoring 36 years ago, according to a report published Thursday.

An AIMS survey of 87 reefs found that between August 2021 and May 2022, average hard coral cover in the upper region and central areas of the reef increased by around one third.

It’s a rare piece of good news for the world-famous reef, which in March underwent its sixth mass bleaching event.

AIMS CEO Dr. Paul Hardisty said the results in the north and central regions were a sign the reef could still recover from mass bleaching and outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish that feed on coral.

However, he emphasized that the loss of coral cover elsewhere in the reef suggests it is still susceptible to threats, like marine heatwaves. The report added that due to climate change, these disturbances that could reverse the progress in coral growth were likely to become more frequent and longer lasting.

AIMS monitoring program team leader Dr. Mike Emslie said that most of the increase was driven by fast-growing Acropora corals which are “particularly vulnerable” to coral bleaching, wave damage caused by tropical cyclones and as prey for the starfish.

“This means that large increases in hard coral cover can quickly be negated by disturbances on reefs where Acropora corals predominate,” Emslie said.

The Australian Marine Conservation Society’s Great Barrier Reef Campaigner Cherry Muddle cautioned that while the report was a sign of progress, the reef remains at risk.

“While this growth is positive and shows the reef is dynamic and can be resilient, it doesn’t discount the fact that the reef is under threat,” Muddle told CNN.

A reef in danger

Four of the reef’s six mass bleaching events have occurred since 2016. The most recent occurred in March this year, with 91% of the reefs surveyed impacted by bleaching, according to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA). That’s significantly more widespread than the time before, when about a quarter of the reef surveyed showed signs of severe bleaching in 2020.

In a May report, the GBRMPA warned that “events that cause disturbances on the reef are becoming more frequent.”

Bleaching is a result of warmer than normal water temperatures which triggers a stress reaction from the corals. However, according to GBRMPA scientists, this year’s coral bleaching was the first time it has occurred during La Ni?a, a weather event which is usually characterized by cooler-than-normal temperatures across the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

According to Jodie Rummer, associate professor of Marine Biology at James Cook University in Townsville, the frequency of the mass bleaching events is cause for concern.

“Even the most robust corals require nearly a decade to recover. So we’re really losing that window of recovery,” Rummer told CNN in March. “We’re getting back-to-back bleaching events, back-to-back heat waves. And, and the corals just aren’t adapting to these new conditions.”

Many public figures, including “Aquaman” actor Jason Momoa and ocean explorer Philippe Cousteau, have called for UNESCO to add the natural wonder to its “in danger” list in hopes that it would incentivize action to save the reef.

Australia’s responsibility

For years, Australia has been criticized for its reliance on fossil fuels. However, the country’s new Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has promised to take greater action to reduce emissions. On Thursday, Australia’s lower house passed a bill to enshrine the government’s commitment to reduce Australia’s emissions by 43% by 2030 in law, though it still needs the approval of the Senate.

However, experts say that a 43% cut in emissions is still not enough to prevent the worsening effects of climate change and further damage to the Great Barrier Reef.

“In Australia, to do our share, we really need to slash our emissions reductions by 75% by 2030 and that is to hold global warming to less than 1.5 degrees which is the critical threshold for the survival of coral reef as we know it,” Muddle told CNN.

“We can create jobs, we can protect the reef, if we only embrace clean energy technology and stop all new coal and gas developments,” she added. “There’s momentum in the right direction but we need to see action, like bold action, and we need to see it now.”