Angela Welch still recalls every detail. The stocky gunman in a camo ?vest. The gunshots, one after another. The piercing screams, echoing through the building. The muffled sobs.

Welch was a high school sophomore in Olivehurst, California, when a former student entered her school on a Friday afternoon with a 12-gauge shotgun in one hand, a .22-caliber rifle slung over his back and a band of ammunition on a belt.

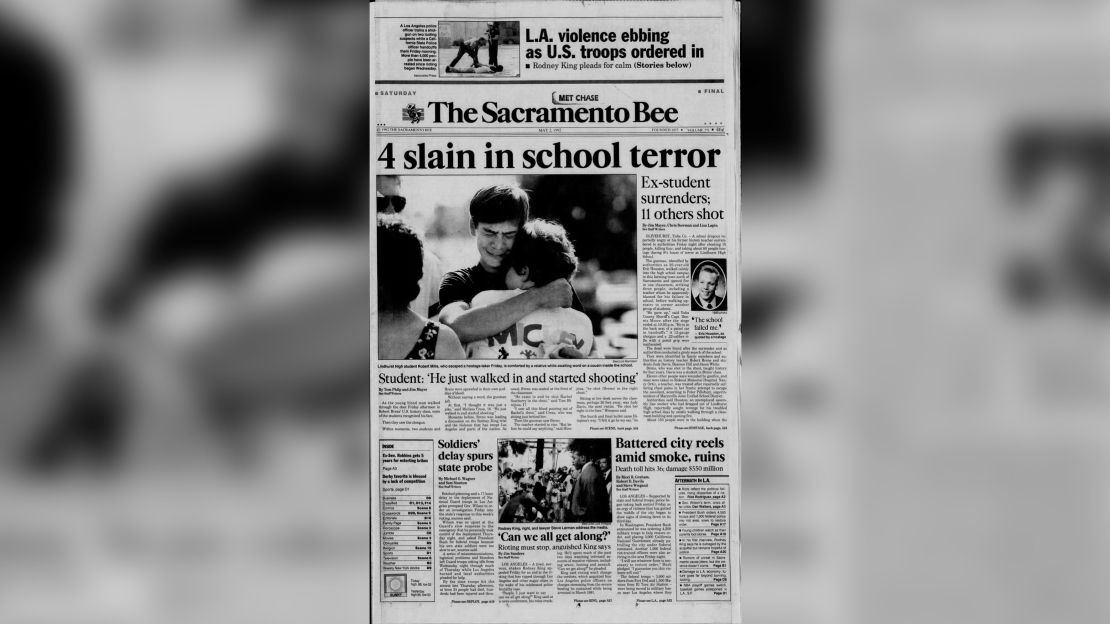

It was May 1, 1992 – seven years before Columbine, before the days of active shooter drills, before anyone imagined a gunman entering a school and harming students would become a common occurrence.

Lindhurst High School was abuzz with anticipation – it was the day before the prom. Then, suddenly, the school erupted in chaos. The vaguely familiar young man stalked the halls, gunning down a teacher, shooting students in classrooms and holding dozens of others hostage.

By the time the eight-hour siege was over, three students and a teacher were dead, and 10 people were wounded, court documents show. The town of about 10,000 north of Sacramento was forever changed.

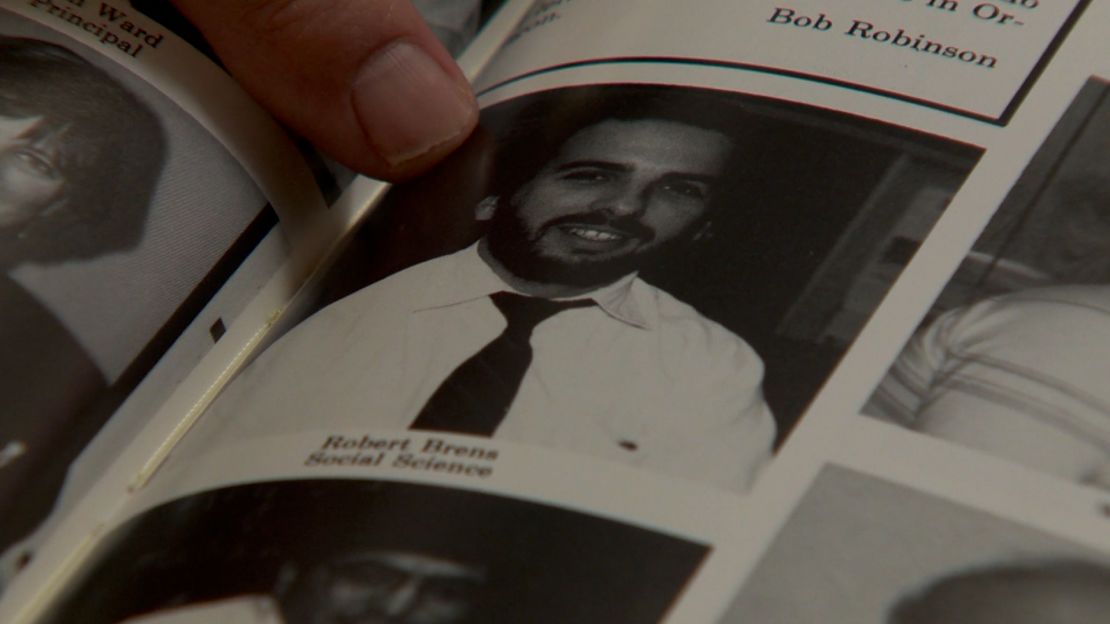

Authorities described the shooter, Eric Houston, then 20, as a Lindhurst High dropout who’d failed to graduate from the school three years earlier and who blamed his former history teacher, Robert Brens, for giving him a failing grade.

CNN spoke to Welch and Lynda Vanartsdalen, a former Lindhurst teacher who also survived the shooting. The two women described a drawn-out day of chaos, terror and questions that still haunt them three decades later.

Back then, attacks on schools were largely unheard of. Vanartsdalen and Welch never imagined so many other school shootings would follow.

“I can’t believe it’s still happening, 30 years later,” Vanartsdalen said.

The women said that every massacre at a school, like the recent one in Uvalde, Texas, brings back harrowing memories.

“I can feel the pain the students feel from losing a classmate,” said Welch, speaking of the Uvalde shooting. It’s a pain that may affect them for years to come, she said.

At first, she thought the shots she heard were seniors popping balloons

That afternoon, Welch recalls, she was in a history class in Building C, preparing for a quiz and chatting about summer plans with her classmates.

With the semester nearing its end, excitement filled the air.

“There were no signs of danger, no threats, everyone going about their day,” Welch said. “Seniors talking smack in the hallways about what they will do after graduation, others talking about summer vacations with friends and family, others making plans to meet up after school.”

Shortly afterward, several loud pops punctuated the students’ chatter.

Welch and her classmates initially dismissed the sounds, she said, thinking that giddy seniors were popping balloons. But the bangs got louder, Welch said, and students in the hallway started screaming.

Moments later, the gunman appeared in the doorway of her class, raised his gun and started firing. Her classmate, Beamon Hill, pushed her out of harm’s way, court documents say.

“Everything was happening so fast,” Welch said. “All I remember is Beamon instantly shoved me to the ground, taking the bullet.”

Welch fell to the floor and saw Beamon sprawled nearby, bleeding from his head, she said. She began weeping as she struggled to understand what was going on.

“Classmates yanked me behind a cabinet to hide and covered my mouth to stay quiet,” Welch said.

Before he reached Welch’s class, Houston had walked into Brens’ classroom and shot him in the chest as the teacher leaned on his desk in front of his students, court documents show.

Witnesses said Houston then turned around, pumped his weapon and shot student Judy Davis in the face and upper chest, court documents show. She tumbled from her seat to the floor. Houston left the room and gunned down senior Jason White in a hallway, then went to the world studies class, where he encountered Welch and Beamon, according to court documents.

Other than Brens, the other victims appeared to be chosen at random, authorities said. Witnesses told prosecutors Houston carried out his massacre impassively, without saying a word.

‘He was really like there was no one inside, no one home, no one in there,” student Gregory Howard later told a grand jury. “He looked like he didn’t have a soul.”

One teacher locked her classroom, turned off the lights and called 911

Vanartsdalen was in the same C building that afternoon.

In a sign of how unusual school shootings were then, one teacher later told her she initially thought the armed man was a soldier visiting from nearby Beale Air Force Base to discuss career options with students.

“It was just a perfect California day, then all hell broke loose,” Vanartsdalen said. “Now every time I hear of another school shooting, my heart breaks. I know the pain and the hurt and the struggle they will go through for years to come.”

A career adviser at the time, Vanartsdalen still remembers the smell of gunpowder in the hall and the sounds of students screaming. She recalls the discordant sound of birds chirping outside her office window as terrified students hid behind cabinets.

Vanartsdalen was in the career center with about two dozen students who had come to research careers during sixth period – the final one of the day, she said. She remembers peeking outside and seeing the shooter pace up and down the hallway.

He fired again and again, unleashing a white cloud.

“There was all this popping and smoke,” Vanartsdalen said. “I can still smell the gunpowder to this day.”

Vanartsdalen removed her classroom’s door stop, closed and locked the door, and turned off the lights. She ordered the students onto the ground as gunshots and screams from other classrooms permeated the walls. She crawled across the floor, pulled a phone down from her desk and punched 911 over and over and over. No one answered, she said.

And then she and the other students waited.

“My mind was going a million miles an hour,” she said.

Some survivors fled the school and took refuge in a nearby house

Houston then herded students into an upstairs classroom in a corner of the building. As he held them captive, he ranted about flunking out of school and blamed it on Brens, court documents said.

Meanwhile, Welch, Vanartsdalen and a group of students stayed in their hiding spots downstairs. After C building quieted down, someone opened an exit door and they all fled.

“We all ran like hell into the neighborhood, banging on people’s doors to let us in,” Welch said.

Vanartsdalen said she led Welch and a group of other students to a nearby house. In her eagerness to let the students inside, the teacher grabbed the screen door with such force that she yanked it off its hinges. The terrified homeowner was reluctant at first but allowed them to stay until Vanartsdalen could use the home’s phone to call all the kids’ parents.

After holing up in the house for hours, Welch was reunited with her father. Vanartsdalen remained at the neighbor’s house until the last child had gone home safely.

Not until she emerged three hours later and walked back to the school did she begin to comprehend the magnitude of what was happening.

“At the time, we thought we were the only survivors,” Vanartsdalen said. “Houston was still holding about 80 students hostage in a classroom, and no one knew what was going on.”

SWAT teams surrounded the building, waiting for the right moment to strike. Police and TV news helicopters hovered overhead.

As afternoon turned into dusk and the sky faded to black, a shell-shocked community awaited word on their loved ones.

The hours dragged on. Houston released a few students in exchange for soda and boxes of pizza.

He finally surrendered about 10:30 p.m., ending a tense standoff.

Vanartsdalen said she was still outside the school when authorities led him out in handcuffs.

That’s when she recognized the shooter as a student who had come to the career center a few years earlier. She remembered a blond, withdrawn teen who barely spoke to anyone and didn’t seem to have many friends.

Three decades later, the shooting’s effects still linger

For Vanartsdalen and Welch, the impact of the tragedy lingers 30 years later.

Welch now 46, works at a hospital’s financial office in Lexington, Kentucky. Vanartsdalen, 71, is retired and lives in Marysville, California, about five miles from Olivehurst.

Both women said surviving a school shooting heightens your alertness in a way nothing else does. Even now, every time they visit a store, restaurant, or other public place, the first thing they do is map out an exit strategy.

Vanartsdalen is wary of hovering helicopters, firecrackers and popping balloons. On a recent dinner date with her husband, she almost panicked when she noticed a man pacing anxiously in the restaurant. The moment passed without incident, but she remains vigilant about her safety.

Both women said they got weeks of counseling and therapy afterward. But back then, therapists were not as equipped to handle mass shootings.

“My therapist seemed so overwhelmed with everything, I stopped going after a while,” Welch said. “What seemed to help more was talking about it with other people in the community, both friends and strangers.”

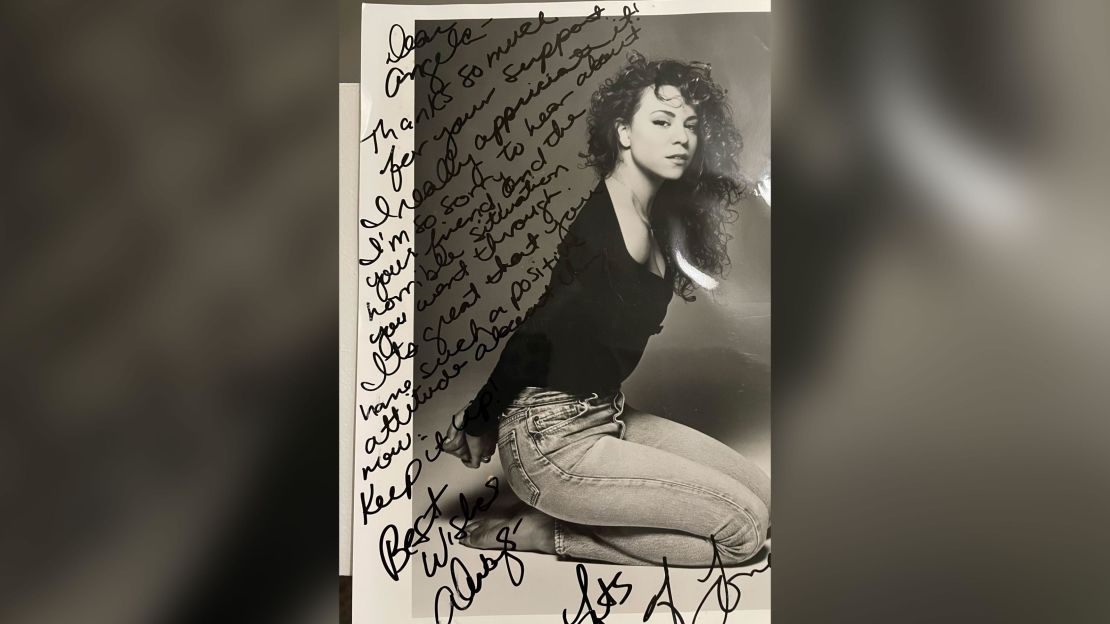

Several months after the shooting, Welch was surprised to receive a package with an autographed photo and a note from Mariah Carey, one of her favorite singers.

“I’m so sorry to hear about your friend and the horrible situation you went through,” it said. “It’s great that you have such a positive attitude about things now.”

And in 1994, Welch was a guest on Oprah Winfrey’s TV show, where she appeared with other survivors of mass shootings and shared her recollections of that fateful day.

“Oprah asked me questions about my experience and how I was handling things now. We did talk a little about Beamon,” she said. “What I remember most is her kindness … her words of encouragement to stay strong and do positive things in life.”

These days, as school shootings become more common, Welch said she’s forced to replay that day over and over. Every new shooting is a trigger – and a reminder of what lies ahead for the survivors.

“Those poor kids from all these school shootings will have to learn how to live their lives going forward,” Welch said.

The women still remember those who died that day. Welch said she will never forget her classmate Beamon’s heroic act. She’s told her two children about the popular 16-year-old prankster who helped keep everyone loose and may have saved their mother’s life.

Welch said she remembers that earlier that day, Beamon had tossed a crumpled-up piece of paper across the classroom. When the teacher asked who did it, he had put on his game face and pointed at Welch. The other classmates erupted into laughter because they knew he was the culprit, she said.

“Beamon got me in so much trouble,” Welch said. “He knew exactly how to make me smile when I was stressed before a test.”

Houston was eventually convicted of four counts of first-degree murder and remains on death row at San Quentin State Prison. The Olivehurst community has largely moved on from the shooting, Vanartsdalen said, and people there rarely talk about it, except on the anniversary.

But revisiting what happened on May 1, 1992, remains a form of therapy for her – and a way to honor those who were lost.

“Four people died that day,” she said. “We should never forget them.”