Standing in front of the historic Red Fort in Delhi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Monday pledged to transform India into a developed country in the next 25 years.

“The way the world is seeing India is changing. There is hope from India and the reason is the skills of 1.3 billion Indians,” Modi said. “The diversity of India is our strength. Being the mother of democracy gives India the inherent power to scale new heights.”

Modi’s words came as millions celebrated 75 years of Indian independence since the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947 that ended nearly 200 years of British colonial rule.

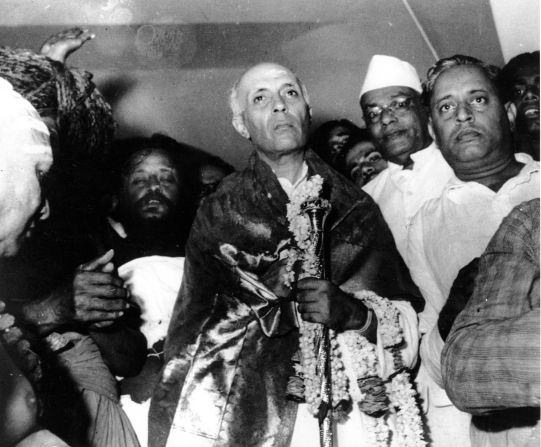

At the time, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said the country was on a path of revival and renaissance.

“A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new,” Nehru said. “When an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

Seventy-five years later, the India of today is almost unrecognizable from that of Nehru’s time.

Since gaining independence, India has built one of the world’s fastest growing economies, is home to some of the world’s richest people, and according to the United Nations, its population will soon surpass China’s as the world’s largest.

But despite the nation’s surging wealth, poverty remains a daily reality for millions of Indians and significant challenges remain for a diverse and growing nation of disparate regions, languages, and faiths.

Rise of an economic power

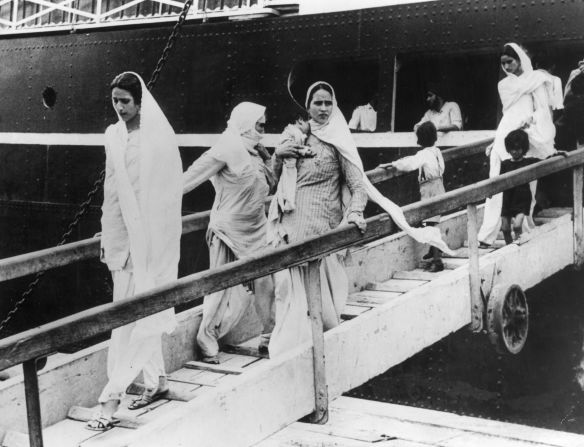

Following independence, India was in chaos. Reeling from a bloody partition that killed between 500,000 and 2 million people, and uprooted an estimated 15 million more, it was synonymous with poverty.

Average life expectancy in the years after the British left was just 37 for men and 36 for women, and only 12% of Indians were literate. The country’s GDP was $20 billion, according to scholars.

Fast forward three-quarters of a century and India’s nearly $3 trillion economy is now the world’s fifth largest and among its fastest growing. The World Bank has promoted India from low-income to middle-income status – a bracket that denotes a gross national income per capita of between $1,036 and $12,535.

75 years of independence: India and Pakistan, in photos

Literacy rates have increased to 74% for men and 65% for women and the average life expectancy is now 70 years. And the Indian diaspora has spread far and wide, studying at international universities and occupying senior roles in some of the world’s biggest tech companies, including Google chief executive Sundar Pichai, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and Twitter boss Parag Agrawal.

Much of this transformation was prompted by the “pathbreaking reforms” of the 1990s, when then Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao and his Finance Minister Manmohan Singh opened the country to foreign investment after an acute debt crisis and soaring inflation forced a rethink of socialist Nehru’s model of protectionism and state intervention.

The reforms helped turbocharge investment from American, Japanese and Southeast Asian firms in major cities including Mumbai, the financial capital, Chennai and Hyderabad.

The result is that today, the southern city of Bengaluru – dubbed “India’s Silicon Valley” – is one of the region’s biggest tech hubs.

At the same time, India has seen a proliferation of billionaires – it is now home to more than 100, up from just nine at the turn of the millennium. Among them are infrastructure tycoon Gautam Adani, whose net worth is more than $130 billion, according to Forbes, and Mukesh Ambani, founder of Reliance Industries, who’s worth about $95 billion.

But critics say the rise of such ultra-wealth highlights how inequality remains even long after the end of colonialism – with the country’s richest 10% controlling 80% of the nation’s wealth in 2017, according to Oxfam. On the streets, that translates into a harsh reality, where slums line pavements beneath high-rise buildings and children dressed in tattered clothes routinely beg for money.

But Rohan Venkat, a consultant with Indian think tank Centre for Policy Research, says India’s broader economic gains as an independent nation shows how it has confounded the skeptics of 75 years ago.

“In a broad sense, the image of India (post independence) was that it was an exceedingly poor place,” said Venkat.

“Certainly the image of India (to the West) was heavily overlaid by Orientalist tropes – your snake charmers, little villages. Some of these were not entirely off the mark … but a lot of it was simple stereotyping.

Since then, India’s trajectory has been “exceptional,” Venkat said.

“To witness the largest transfer (of power) from an elite ruling the state, to now becoming a complete universal franchise … we are looking at an incredible political and democratic experiment that is unique.”

Rise of a geopolitical giant

For years after independence, India’s international relations were defined by its policy of non-alignment, the Cold War era stance favored by Nehru that avoided siding with either the United States or the Soviet Union.

Nehru played a leading role in the movement, which he saw as a way for developing countries to reject colonialism and imperialism and avoid being dragged into a conflict they had little interest in.

That stance did not prove popular with Washington, preventing closer ties and marring Nehru’s debut trip to the US in October 1949 to meet President Harry S. Truman. During the 1960s the relationship became further strained as India accepted economic and military assistance from the Soviets and this frostiness largely remained until 2000, when President Bill Clinton’s visit to India prompted a reconciliation.

Today, while India remains technically non-aligned, Washington’s need to balance the rise of China has led it to court New Delhi as a key partner in the increasingly active security grouping known as the Quad.

The grouping, which also includes Japan and Australia, is widely perceived as a way of countering China’s growing military and economic might and its increasingly aggressive territorial claims in the Asia Pacific.

India, meanwhile, has its own reasons for wanting to counterbalance Chinese influence, not least among them its disputed Himalayan border, where more than 20 Indian troops were killed in a bloody battle with Chinese counterparts in June 2020. In October, the US and India will hold a joint military exercise less than 100 kilometers (62 miles) from that disputed border.

As Happymon Jacob, an associate professor of diplomacy and disarmament at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, put it: “India has been able to assert itself on the world stage because of the nature of international politics today and the political and diplomatic military capital that has been put in place by previous governments.”

Part of India’s growing geopolitical clout is due to its growing military expenditure, which New Delhi has ramped up to counter perceived threats from both China and its nuclear-armed neighbor, Pakistan.

Following their separation in 1947, relations between India and Pakistan have been in a near constant state of agitation, leading to several wars, involving thousands of casualties and numerous skirmishes across the Line of Control in the contested Kashmir region.

In 1947, India’s net defense expenditure was just 927 million rupees – about $12 million in today’s money. By 2021, its military expenditure was $76.6 billion, according to a report from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute – making it the third highest military spender globally, behind only China and the US.

Ambitions on the world stage

Outside economics and geopolitics, India’s growing wealth is feeding its ambitions in fields as diverse as sport, culture and space.

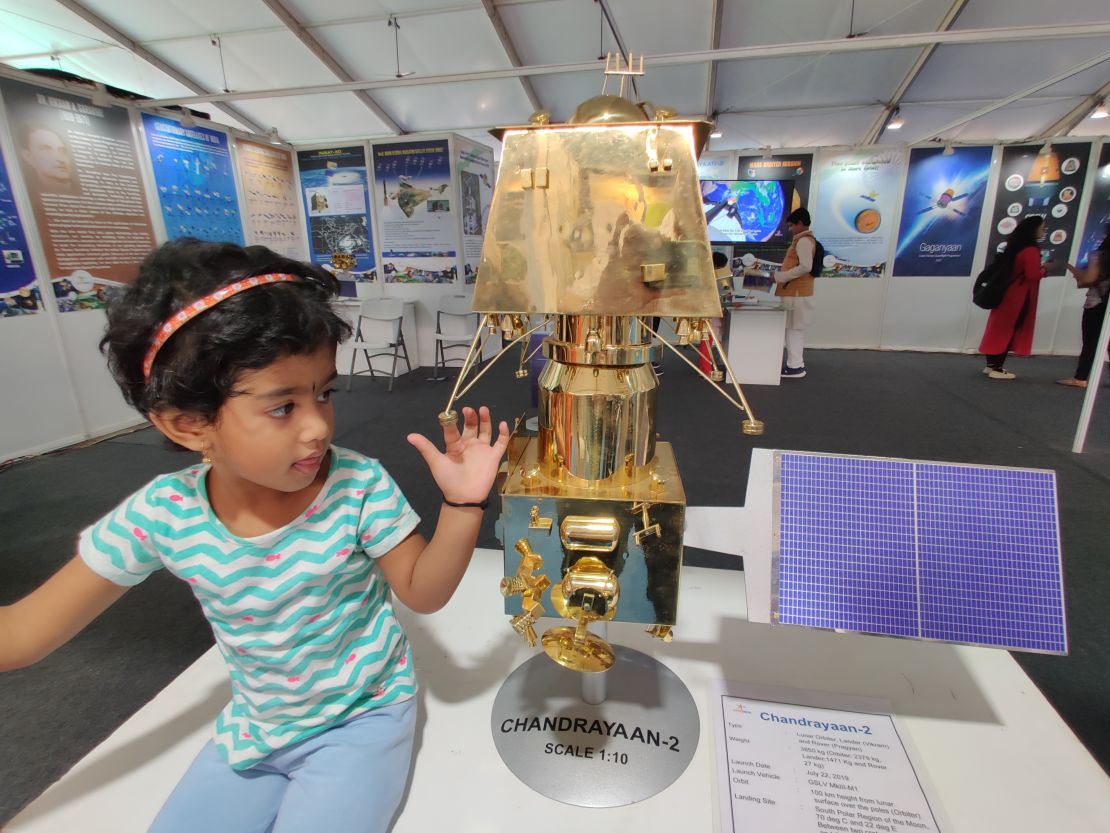

In 2017, the country broke a world record when it launched 104 satellites in one mission, while in 2019, Prime Minister Modi announced that India had shot down one of its own satellites in a military show of force, making it one of only four countries to have achieved that feat.

Later that year, the country attempted to land a spacecraft on the moon. Though the historic attempt failed, it was widely seen as a statement of intent.

Last year, the country spent almost $2 billion on its space program, according to McKinsey, trailing the biggest spenders, the US and China, by some margin, butIndia’s ambitions in space are growing. In 2023, India is expected to launch its first manned space mission.

The country is also using its growing wealth to boost its sporting prospects, spending $297.7 million in 2019 before the spread of Covid-19.

The Indian Premier League – the country’s flagship cricket tournament launched in 2007 – has become the second most valuable sports league in the world in terms of per-match value, according to Jay Shah, secretary of the Board of Control for Cricket in India, after selling its media rights for $6.2 billion in June.

And Bollywood, India’s glittering multibillion dollar film industry, continues to pull in fans worldwide, catapulting local names into global superstars attracting millions of followers on social media. Between them, actresses Priyanka Chopra and Deepika Padukone have almost 150 million followers on Instagram.

“India is a strong country. It’s an aggressive player,” said Shruti Kapilla, a professor of Indian history and global political thought at Cambridge University.

“In the last couple of decades, things have shifted. Indian culture has become a major story.”

Challenges and the future

But for all of India’s successes, challenges remain as Modi seeks to “break the vicious circle of poverty.”

Despite India’s large and growing GDP, it remains a “deeply poor” country on some measures and that, consultant Venkat said, is a “tremendous concern.”

As recently as 2017, about 60% of India’s nearly 1.3 billion people were living on less than $3.10 a day, according to the World Bank, and women still face widespread discriminationin the deeply parochial country.

Violence against women and girls has made international headlines in a country where allegations of rape are often underreported, due to the lack of legal recourse for alleged attackers through a legal system that’s notoriously slow.

“Many of India’s fundamental challenges remain what they were at the time of independence in some ways, at different parameters and scale,” Venkat said.

India is also on the front line of the climate crisis.

Recent heat waves – such as in April when average maximum temperatures in parts of the country soared to record levels and New Delhi saw seven consecutive days over 40 degrees Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) – have tested the limit of human survivability, experts say.

And it’s the country’s poorest people who are set to suffer the most, as they work outside in oppressive heat, with limited access to cooling technologies that health experts say is needed to contend with rising temperatures.

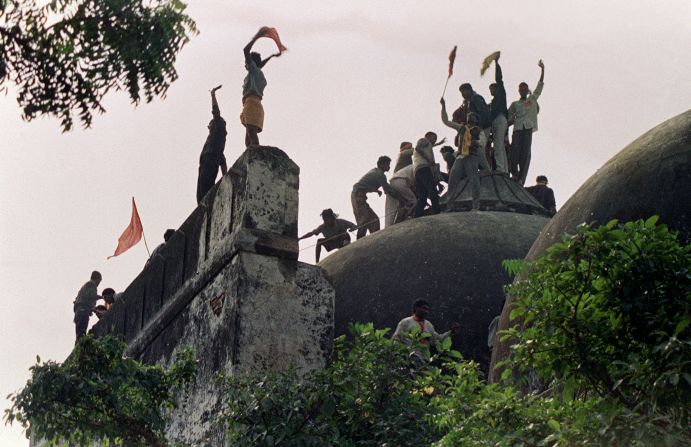

And as the heat rises on the land, political pressure has grown with fears that the secular fabric of the country and its democracy are being eroded under the leadership of Modi, whom critics accuse of fueling a wave of Hindu nationalism that has left many of the country’s 200 million Muslims living in fear.

Many states run by his ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have introduced legislation critics say is deeply rooted in Hindutva ideology, which seeks to transform India into the land of the Hindus. And there has been an alarming rise in support for extremist Hindu groups in recent years, analysts say – including some that have openly called for genocide against the country’s Muslims.

At the same time, the arrests of numerous journalists in recent years have led to concerns the BJP is using colonial-era laws to quash criticism. In 2022, India slipped to number 150 on the Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders – its lowest position ever.

“The challenges now are about India’s nature of democracy,” Kapilla said. “India is going through a major, contentious change at the fundamental political level.”

Seventy-five years on, Nehru’s observation that “freedom and power bring responsibility” continue to ring true.

India’s first 75 years ensured its survival, but in the next 75 years it needs to navigate immense challenges to become a truly global leader, and not just in terms of population, said Venkat, from the Centre for Policy Research.

“Although (India) may end up being the world’s fastest growing major country over the next few years, it will still be miles behind its neighbor in China, or getting close to what it had hoped to achieve at this point, which was double digit growth.”

“So the challenges are immediate and all over the place, chief among them being how to ensure its prosperity,” Venkat said.