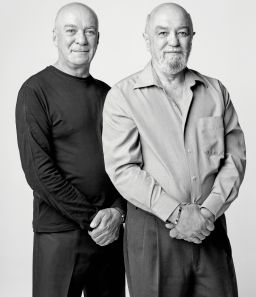

Sometimes when Charlie Chasen or Michael Malone would be out and about on their own in Atlanta, people would mistake one for the other.

The long-time friends who live in Atlanta are not related. Their ancestors don’t even come from the same part of the world. Malone’s family came from the Bahamas and the Dominican Republic. Chasen’s family came from Scotland and Lithuania. They aren’t the result of some deep dark family secret, either. Yet they look strikingly similar. It’s not just their brown hair, beards and glasses. It’s also the structure of their nose, their cheekbones, and the shape of their lips.

“Michael and I go way back and it’s all been like a source of a lot of fun for us because over the years, we’ve been mistaken for each other all over the place all over Atlanta,” Chasen told CNN’s Don Lemon. “There’s been some really interesting situations that have come out just because people thought we were the other person.”

The two look so similar, even facial recognition software had a hard time telling them apart from identical twins. But now scientists think they can explain what it is that makes them look so similar – and could explain why each of us may have doppelg?nger.

People who resemble each other, but are not directly related, still seem to have genetic similarities, according to a new study.

Among those who had these genetic similarities, many also had similar weights, similar lifestyle factors, and similar behavioral traits like smoking and education levels. That could mean that genetic variation is related to physical appearance and also, potentially may influence some habits and behavior.

Scientists have long wondered what it is that creates a person’s doppelg?nger. Is it nature or nurture? A team of researchers in Spain tried to find out. Their results were published in the journal Cell Reports on Tuesday.

Dr. Manel Esteller, a researcher at the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, said that he worked on research involving twins in the past, but for this project, he was interested in people who look alike but have no actual family connection going back almost 100 years.

Art leads to science

So, he turned to art to answer a question about science. He and his co-authors recruited 32 people with look-alikes who were part of a photo project “I’m not a look-alike!,” done by a Canadian artist, Fran?ois Brunelle.

The researchers asked the pairs to do a DNA test. The pairs filled out questionnaires about their lives. The scientists also put their images through three different facial recognition programs. Of the people they recruited, 16 pairs had similar scores to identical twins identified using the same software. The other 16 pairs may have looked the same to the human eye, but the algorithm didn’t think so in one of the facial recognition programs.

Researchers then took a closer look at participants’ DNA. The pairs the facial recognition software said were similar had many more genes in common than the other 16 pairs.

“We were able to see that these look alike humans, in fact, they are sharing several genetic variants. And these are very common among them,” Esteller said. “So they share these genetic variants that are related in a way that they have the shape of the nose, the eye, the mouth, the lips, and even the bone structure. And this was the main conclusion that genetics puts them together. ”

These are similar codes, he said, but it is just by random chance.

“In the world right now, there are so many people that eventually the system is producing humans with similar DNA sequences,” Esteller said. This likely was always true, but now with the internet, it’s a lot easier to find them.

Other factors at play

When they looked closer at the pairs, they determined other factors were different, he said.

“There’s the reason they are not completely identical,” Esteller said.

When scientists looked closer at what they call the epigenomes of the doppelg?ngers that looked most alike, there were bigger differences. Epigenetics is the study of how the environment and behavior can cause changes in the way a person’s genes work. When the scientists looked at the microbiome of the pairs that looked most alike, those were different, too. The microbiome are the microorganisms – the viruses, bacteria, and fungi too small to see with the human eye – that live in the human body.

“These results not only provide insights about the genetics that determine our face but also might have implications for the establishment of other human anthropometric properties and even personality characteristics,” the study said.

The study does have limitations. The sample size was small, so it is difficult to say that these results would be true for a larger group of look-alikes. Although researchers believe that their findings would change in a larger group. The study also focused on pairs that were largely of European origin, so it is unclear if the results would be the same for people who come from other parts of the planet.

Dr. Karen Gripp a pediatrician and geneticist at Nemours Children’s Health whose research is referenced in this work, said the study is really interesting and validates a lot of the research that comes before it.

Real world application of the science

Gripp uses facial analysis software in her work with patients who might have genetic conditions to assess her patient’s facial features which might be suggestive of certain genetic conditions.

“It’s a little bit different from the study, but it really points in the same direction that changes in a person’s genetic material affect the facial structures, and that’s really the same underlying assumption that was used in this study as being indeed confirmed, in contrast to some other things like the microbiome did not seem to be as relevant,” Gripp said.

As far as the nature versus nurture question the study brings up, Gripp thinks that both are important.

“As a geneticist, I firmly believe in the nature and the genetic material being very important to almost everything, but that does not take away from saying nurture is just as important,” Gripp said. “For every person to be successful in the world there are so many contributing factors and the environment is so important that I don’t think it’s one or the other.”

A potential problem

The study she said also points out that there are still limits to the accuracy of facial recognition software. While several cities concerned about privacy issues and misidentification problems have enacted rules banning or restricting local police from using facial-recognition software, the federal government and some local law enforcement have been using it more frequently.

A 2021 federal investigation found that at least 16 federal agencies use it for digital access or cybersecurity, 6 use it to generate leads in criminal investigations, and 10 more said they planned to expand its use.

It’s also used more commonly at airports. Some companies use it to help make hiring decisions. Some landlords have installed it so tenants can enter buildings. Some schools use it to take attendance and to monitor movements in public spaces on college campuses.

“If you translate this study into the real world, that shows you a potential pitfall that digital facial analysis tools could misidentify somebody,” Gripp said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

While the technology has been improving, in past studies, the technology has already been shown to be far less accurate when identifying people of color, and several Black men, have been wrongfully arrested due to facial recognition.

“If you think about the facial recognition software that often opens computer screens and things like that, misidentification is possible. So I think this has taught us something very important about facial analysis tools too,” Gripp said.

But the study does seem to suggest one conclusion. At least physically, we may not be all that unique.

“I think all of us right now have somebody that looks like us, a double,” Esteller said.

While some would prefer to be singular in their look, Malone, who happens to be friends with his double, is heartened by the fact that he is not alone in his looks. His similarity to his friend has made them closer, and he thinks if more people knew how similar they were to others, that maybe they, too, could find commonality, especially in this polarized world.

“It’s made me realize that we are all connected,” Malone said. “We’re all connected because humankind probably starts with one little thing.”