Mikhail Gorbachev’s tragedy is that he outlived the thaw in the Cold War between Moscow and the US, after doing more than anyone to engineer it.

The last leader of the Soviet Union died on Tuesday at the age of 91, with Washington and the Kremlin on opposite sides of President Vladimir Putin’s hot war in Ukraine, launched in part to avenge the Soviet collapse precipitated by Gorbachev’s rule.

It is hard to encapsulate what Gorbachev meant to Western publics in the 1980s, after one of the most dangerous periods of the standoff between East and West. After generations of severe, hostile, hardline and elderly Kremlin leaders, he was young, modern, and fresh – a visionary and a reformer.

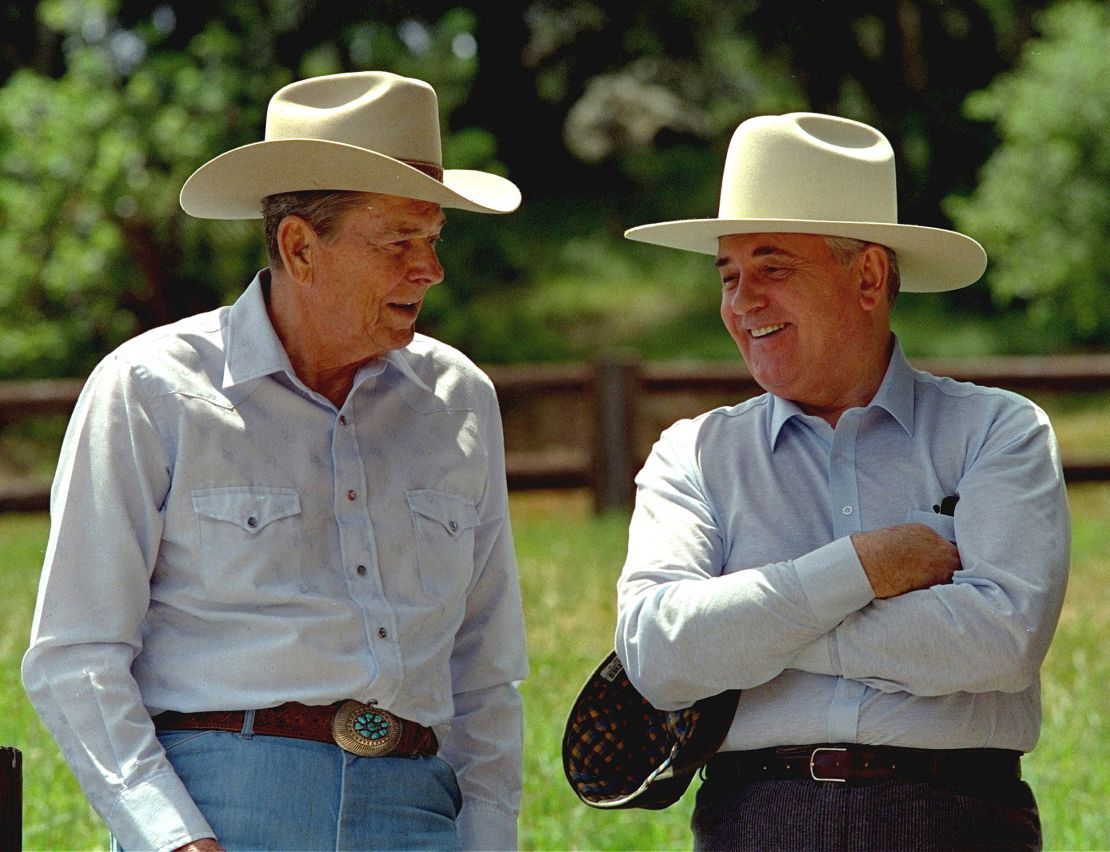

Gorbachev inspired sudden hope that the nuclear showdown that haunted the world in the second half of the 20th century would not end up destroying civilization. US President Ronald Reagan and his British soulmate, Margaret Thatcher, were the most hawkish of Cold warriors. But to their credit, they realized a moment of promise — as the British Prime Minister said of the Soviet leader: “We can do business together.”

Everybody remembers the day when Reagan went to Berlin and against the backdrop of the Brandenburg Gate – which had been defaced by the ugly and inhumane concrete barrier between East and West – said: “Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” It was one of the most iconic moments of modern US history. At the time, few people thought it was possible. In fact, some White House aides thought the comments overly provocative and tried to persuade Reagan not to say them. But in the end, in an act of great humanity, Gorbachev effectively did tear down that wall.

After a heady series of nuclear arms control reduction talks and meetings with Western leaders, Gorbachev became a hero in the West. But it was his decision not to intervene with military force when popular rebellions erupted against Communist regimes in Warsaw Pact nations in 1989 that led to the liberation of Eastern Europe, the fall of the Iron Curtain, the end of the Cold War and the reunification of Germany.

That outburst of freedom bequeathed 30 years of relative peace in Europe.

Lionized in the West, a pariah at home

But while he was lionized in the West, Gorbachev came to be seen as a pariah at home. It is often forgotten now that his goal wasn’t necessarily to dismantle the communist Soviet Union. In many ways, his hand was forced by decades of economic decay in the communist system and the draining impact of a nuclear arms race with the West.

But in trying to save the system, he set off forces that destroyed it. Far from heralding the “end of history” as was often said at the time, his influence caused consequences that could still be felt on the day he died, with Moscow and the West again at loggerheads in a Cold War-style chill.

At home, Gorbachev had two overarching ideas, glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). The swift collapse of the Soviet Union, which perestroika caused to splinter, brought extreme economic conditions, disorder and a blow to national pride. All of this added up to the circumstances that eventually made a strongman like Putin attractive to many Russians.

At the moment when Gorbachev refused to send the Red Army into Eastern Europe to save the communist bloc, Putin was stationed with the KGB in East Germany and felt the sting of Moscow’s desertion. He came to see the demise of the Soviet Empire as a disaster of history; and once Putin gained power, he set about restoring wounded Russian national prestige.

Now the world is saddled with a leader in the Kremlin, who unlike Gorbachev is ready to remake the map of Europe by force — even if a restoration of the Warsaw Pact is beyond his reach, with millions in Eastern Europe now effectively living out Gorbachev’s legacy in democratic, free societies.

Gorbachev’s rule was not without blemishes from a Western point of view. He sent tanks into Lithuania to crush independence hopes in the Baltic states in 1991, months before leaving power. And he was banned from Ukraine for five years after saying he supported Putin’s annexation of Crimea.

But to the end of his days, Gorbachev decried Putin’s excesses and traveled the globe warning of the peril of the plunge in relations between the world’s two top nuclear powers. That he will be remembered as a giant in the West and a pariah at home speaks to the gulf in understanding and experience that again poisons East-West relations.

Gorbachev never stopped mourning his beloved wife, Raisa, who died of leukemia in 1999. Now, he’s followed her and his contemporaries from a remarkable moment in history — Reagan, Thatcher, President George H.W. Bush, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and French President Fran?ois Mitterrand – to the grave.

Everywhere but Russia, he will be remembered as one of those rare figures in history, who by character and vision really did change the world.