Editor’s Note: Lucy Fulford (@lucyfulford) is a journalist and filmmaker focused on migration, conflict and climate. She is the author of a forthcoming book, “The Exiled: Empire, Immigration and How Ugandan Asians Changed Britain.” The views expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

The plane carrying 193 passengers circled down over London Stansted Airport, where a cluster of journalists were waiting to document its arrival. Stepping onto the tarmac under typically gray English skies, the families clutched their scant possessions in briefcases and boxes, saris flowing in the wind.

Five decades after the first evacuation flight of Ugandan Asians touched down in the United Kingdom on September 18, 1972, their story has been held up as a triumph of British generosity and migratory success.

But the back story is less heroic, as the British government first tried to send them anywhere else.

In early August 1972, Uganda’s brutal military dictator Idi Amin ordered the expulsion of the country’s entire Asian population – including my grandparents. An estimated 55,000 to 80,000 Ugandan Asians were given 90 days to leave, with just a single suitcase and £50 each to their name (the limit of what they were allowed to take out of the country).

Amin had accused the Asian population of sabotaging the economy and warned that anyone refusing to leave would “find themselves sitting on the fire.”

Despite making up a small minority of the population, Asians dominated the Ugandan economy. They had also been favored above Ugandans in the colonial hierarchy, sowing seeds of discontent.

My grandparents – British passport holders originally from India – were among the roughly 28,000 Ugandan Asians who fled to the UK, with thousands also settling in Canada, India and elsewhere across the globe.

In their final weeks in Uganda, my grandparents Rachel and Philip wept as new owners took their beloved dog, an Alsatian named Simba. Their cat was shot dead by a neighbor who had long thought it a nuisance. The final journeys to Entebbe Airport were for many dogged by harassment, violence and robberies at military checkpoints. But my family made it through safely, taking one final look at the country they had called home for 19 years.

A British route

In the late 19th century, the British imperial authorities brought indebted laborers from India (a country under British rule) to East Africa to build hundreds of miles of railway from Kenya to Uganda (a British protectorate). These migrant workers later launched shops and businesses, while the British administration continued to recruit Indians to work for them.

As for my grandparents, in 1953 they were approached in southern India by a British education officer touting jobs for maths and science teachers like them in Uganda. They were offered attractive pay, career opportunities and lifestyles. Two adventurous spirits, they soon began their journey by boat to Mombasa, Kenya, and then rail to Kampala, the Ugandan city on seven hills.

In the neighborhood of Kololo, my mother, her brother and sister grew up in a bungalow shaded by leafy trees. Life was good for them, with perfect temperate weather, a bustling social scene and a rich education system.

And a British welcome

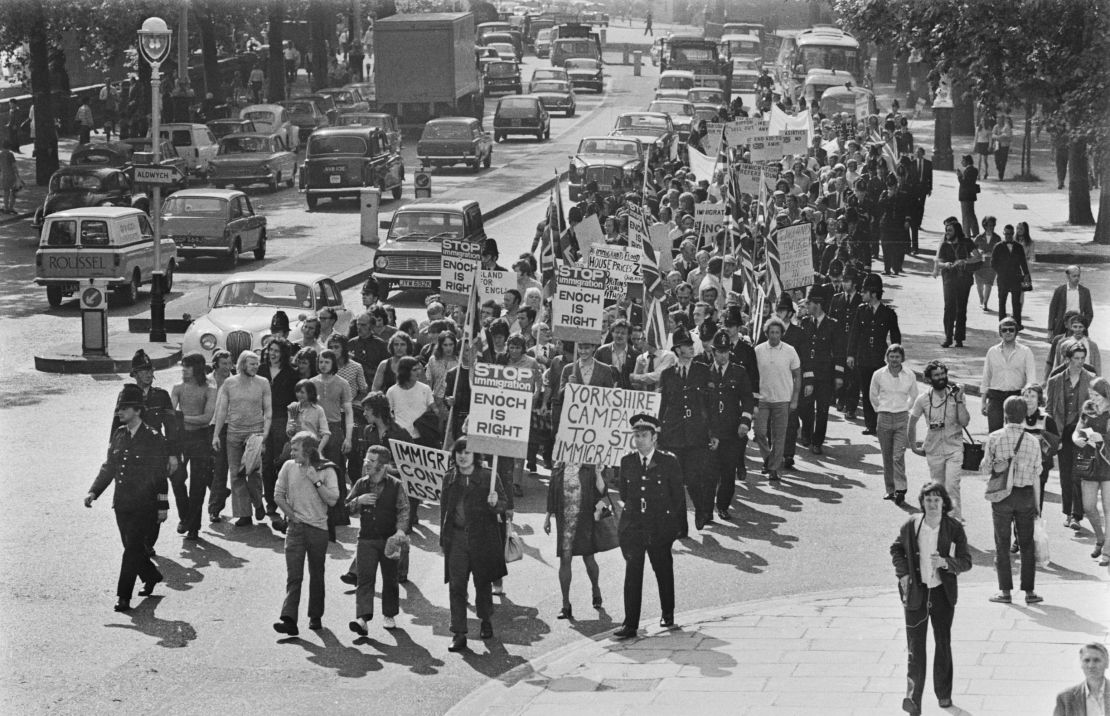

But when Amin gave his expulsion order, the British government didn’t leap into action. Border controls had been tightened in recent years through two Commonwealth Immigrants Acts, restricting automatic right of entry. Anti-immigration sentiment was strong – this was the era of politician Enoch Powell’s infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech – and unemployment was high.

Soon after, the government went on what historian Sanjay Patel describes as a “diplomatic offensive,” desperately seeking to resettle people anywhere else. From India to Australia, Canada to Mauritius, Westminster sent telegrams across the globe. By mid-September, Britain had approached over 50 governments to try and reduce the numbers they had to take in themselves.

Astonishingly, politicians even floated the idea of sending the expellees to remote islands including the Solomon and Falkland Islands. Or offering £2,000 payments in exchange for traveling to India and renouncing the right to live in Britain.

Councillors in the English city of Leicester went as far as to take out a now notorious advert in the Ugandan Argus newspaper warning people off travel, something the city’s current mayor has said he was “deeply ashamed” of. “In your own interests and those of your family, you should… not come to Leicester,” it read.

There was also a deliberate shift in rhetoric sought to reframe the migration of legitimate passport holders from a post-colonial responsibility to a refugee crisis – making the Ugandan Asians the responsibility of the global community, not just Britain. When Edward Heath’s government begrudgingly accepted responsibility, volunteers were placed at the heart of the resettlement program, presenting the exodus as a humanitarian crisis.

Growing up, I never identified as being a child of refugees – and as British passport holders, by definition, my family and the bulk of those expelled were not. But many people within the Ugandan Asian community describe themselves this way, perhaps in part because the experience of displacement lends itself to this feeling, but I think also because they were made to feel this way.

Arriving at London’s Heathrow Airport in November 1972, in light clothes unfit for winter far from the equator, my family were welcomed into an English family’s village home, before moving into a house provided by a Methodist church. Empty, but fully furnished, it had everything they needed to start over, thanks to the generosity of strangers.

A rags-to-riches tale

Starting over with nothing has become the root of the success story indelibly linked with Ugandan Asians ever since, a rags-to-riches odyssey pedaled by politicians, in which Britain held its arms wide open. In this 50th anniversary year some coverage has defaulted to such narratives, and it is bought into by many in the community themselves.

Former Prime Minister David Cameron has referred to Ugandan Asians as “one of the most successful groups of immigrants anywhere in the history of the world,” a legacy many British Ugandan Asians are rightly proud of. Their members went on to run multinational businesses, become community leaders and sit in the House of Lords. But by holding them up as a model minority, it reiterates “good immigrant” tropes and offers a justification to critique any migrants who fall below arbitrary standards.

This year outgoing Prime Minister Boris Johnson boasted that “the whole country can be proud of the way the UK welcomed people fleeing Idi Amin’s Uganda… This country is overwhelmingly generous to people fleeing in fear of their lives and will continue to be so.”

Immigration in 2022

But fast-forward 50 years and the UK government is now overseeing some of the harshest immigration policies on record – from the attempted offshore processing in Rwanda of asylum seekers to the passing of the Nationality and Borders Act, which allows British people to be stripped of their citizenship without notice and asylum seekers to be criminalized depending on how they arrived in the country.

While Ugandan Asians had a pre-existing right to settle in the UK, everyone has the right to asylum from persecution in other countries, as my family were able to.

Far from a graceful welcome, the reality was that a state which had previously directly recruited my grandparents from India to work for them, tried to render them stateless.The limits of 1972’s British welcome have been twisted to serve political aims. Today’s official immigration stance could not be rationally described as “overwhelming generous.”

The journey of Ugandan Asians shows we should celebrate the individuals who stand up and make a difference, and not let others take credit for their efforts – both then, and now.

The writer wishes to identify some family members by first names.