Editor’s Note: Rosa Prince is editor of The House magazine. She is the former assistant political editor of The Daily Telegraph and author of the books “Theresa May: The Enigmatic Prime Minister” and “Comrade Corbyn: A Very Unlikely Coup.” The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

It was a service for a great Queen, a world leader whose long shadow loomed over our age – and at the same time a moving, almost intimate tribute to a beloved mother, grandmother and great-grandmother.

A funeral of pomp and splendor for Queen Elizabeth II brought Britain to a standstill. It prompted 100 heads of state to travel to London – joining a 2,000-strong congregation in Westminster Abbey – and inspired millions around the world to pause and watch the ceremonies for a departed sovereign unfold.

With the late Queen now interred beside her husband, Prince Philip, in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, Britain closes a chapter on its past, a farewell to members of the wartime generation that saw this country’s finest hour, encapsulating as they did the spirit of 1940, when Britain stood alone against fascism, undaunted and unbowed.

The abbey’s tenor bell tolled 96 times as the dignitaries arrived, one for every year of the monarch’s life, a tally that for her subjects was far more than a number.

Her seven decades on the throne meant only the most elderly could remember an era before the age of Elizabeth. Yet the passing of a woman who had achieved such longevity meant the funeral was marked by respect and awe rather than tragedy; there was none of the raw grief that accompanied the death of her former daughter-in-law Princess Diana, who lost her life in shocking circumstances a quarter century earlier almost to the day, in a mangled wreck of a car in a Paris underpass, aged 36.

There has been an air of trepidation to the 10 days of mourning for the Queen, spurred by two questions: What will the future hold under King Charles III, and what does his mother’s departure mean for Britain’s place in the world?

Queen Elizabeth II inherited from her father, King George VI, a country that still claimed an empire, with 70 territories across the globe. For all that she oversaw a successful transition to a more egalitarian Commonwealth of nations, it is hard not to view her reign as one of steady diminution of the United Kingdom’s place on the world stage.

Her death perhaps heralds another lurch down the scale. The soft power the monarchy under Elizabeth conferred on the UK was mighty – what other global leader could command to their funeral such a lineup of world statesmen, from US President Joe Biden to South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Brazilian leader Jair Bolsonaro and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand?

But with republican sentiment rising across the Commonwealth – and, whisper it, perhaps even at home – will the same be true when the time comes to say goodbye to King Charles III?

Or further down the line of succession, his son William, his grandson George? Will they (could they – could anyone?) command the universal admiration and acclaim Queen Elizabeth II inspired?

When she ascended the throne, the great wartime leader Winston Churchill was back in Downing Street;with serendipity, he would become her first Prime Minister. When Churchill died more than 10years later it was said that two rivers ran through London – in addition to the Thames, one made of people lining the streets to pay their respects as his body lay in state in Parliament’s 11th century Westminster Hall.

In the five days leading up to her funeral, that river ran again for Elizabeth II, Churchill’s young Queen who was a living embodiment of a link back to the war, a reminder that Britain had once been great – and could be again.

During those days and nights, the nation’s focus settled on the queue of many hours’ duration to file past her coffin, lying where Churchill’s had nearly six decades earlier.

“The Queue” – it gained capital letters round about the second day – became something of a microcosm of the Queen’s reign and attitudes toward the monarchy.

It was stoic, uncomplaining, self-sacrificing and above all long – very, very long. Those lining up waited up to 24 hours to pay their respects.

By the time the queue was closed, an estimated 300,000 had filed past the Queen’s coffin, the jovial spirit of the line suddenly quelled as mourners reached the echoing cavern of the timber-roofed Westminster Hall, where Charles I was tried and sentenced to death, Henry VIII may have played tennis and Elizabeth’sown parents and grandparents lay in state before her.

A repeated refrain from those lining up was that the late Queen had given 70 years of duty and service; for them to sacrifice a day or night in mild discomfort was fair tribute.

Polls suggest that by the end of her reign, around 25% of the public no longer wished to dwell within a monarchy, with the young less keen than their elders on a nonelected head of state.

It was a point of view largely absent from the national debate during the 10 days of official mourning.

But while even the most ardent republican would confess to admiration for the Queen’s long years of service, and sympathy for her family, it was not hard to detect a collective raised eyebrow at what some saw as elements of overreaction – the curry restaurants and pet stores issuing sorrowful messages on social media were harmless enough, but was it really necessary for food banks to close and cancer treatments to be canceled?

The concept of Britain without a monarchy was far from the thoughts of most, however, on the day of the Queen’s funeral. Many reported feeling moved, often unexpectedly, millions watching spellbound as the national show of mourning unfurled: religion, politics and the military all playing their roles alongside the grieving family.

At the close of the service, in the magnificent abbey she entered as a bride in 1947 and, as were kings and queens of England dating back to King Edgar in the 10th century, duly crowned in 1953, the still unfamiliar national anthem of “God Save the King” rang out.

In the front pew, the man they were hailing, King Charles III, was red-eyed, almost shell-shocked at the weight of responsibility that now falls on his shoulders.

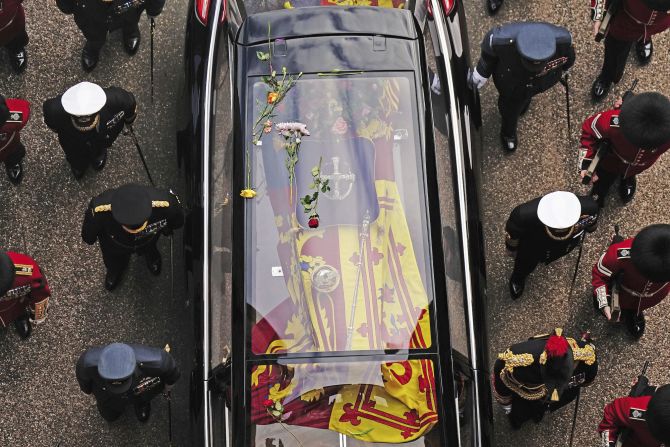

Then the late monarch left the capital for the last time, the gun carriage departing for Windsor, where the ceremonies would continue into the afternoon.

Elizabeth II was the greatest Queen our age has known, a defining figure of the 20th and early 21st centuries. A little of Britain’s prestige has been buried with her – her heirs and her people will hope something new, different, but no less powerful, can rise from her memory.