You’ve been working and saving for decades for just this moment: retirement.

Even though you may be ready to stop working full-time, now comes the hard part: Actually letting yourself use your savings, since you no longer will be bringing in that paycheck, which until now has covered your monthly expenses.

Making the psychological shift from saver to spender – not to mention nest egg manager – is no small feat for most people.

“Now you have this lump sum and have to draw it down. For some it’s almost physically painful,” said David John, a senior strategic policy advisor at the AARP Public Policy Institute.

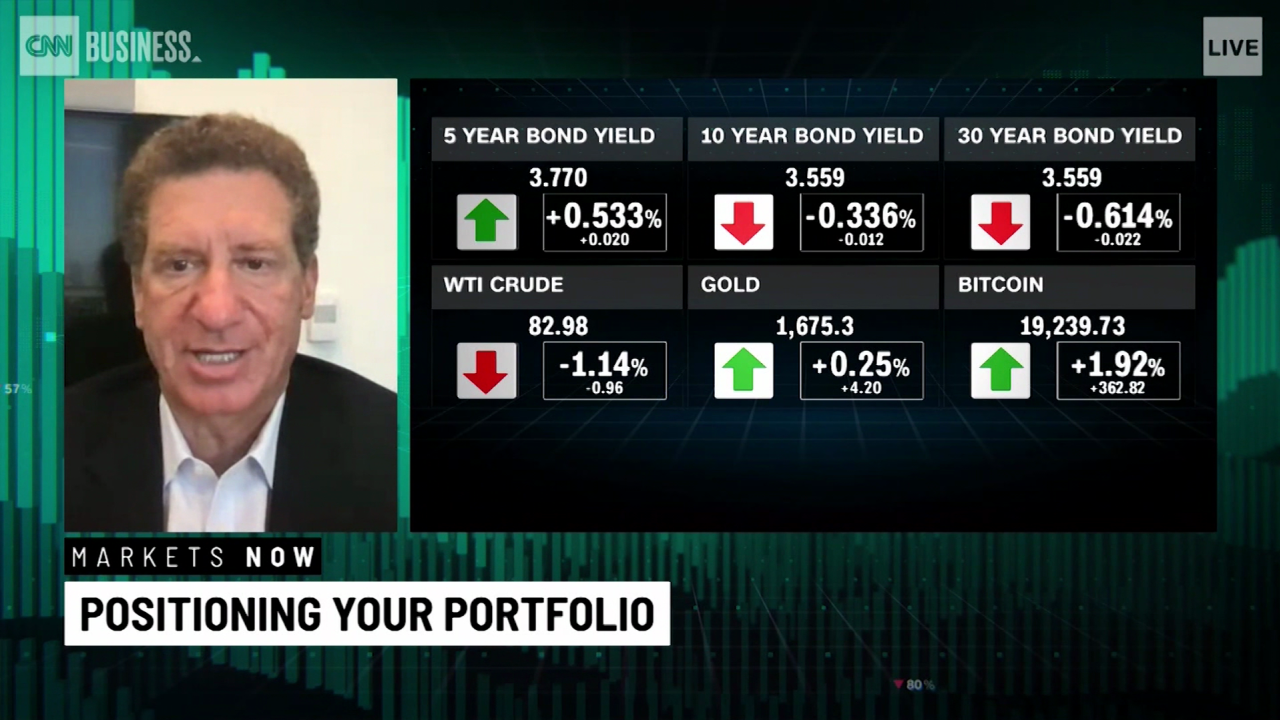

But unpredictablefactors like market performance, life expectancy and health issues make spending your money easier said than done, John said. That’s why people may be hesitant to tap their savings because they think, “I have X dollars and it has to last me my whole life, but I have a very uncertain future. So if I touch that I’m putting myself in jeopardy.”

And research shows that among retirees with savings, many do not draw down very much, choosing instead to live off fixed sources of funds, such as Social Security or pensions or income from part-time work they take up. A study by Black Rock found that the vast majority of retirees still have at least 80% of their savings after two decades in retirement.

No doubt that’s partly because they enjoyed one of the longest bull markets in history from 2009 to 2020, which helped replenish some of what they drew down over the years. And they’re among the last generation of workers to benefit from corporate pensions.

But the psychological reluctance to tap one’s savings is a factor for most people regardless of their financial wherewithal. And it may become more acute for soon-to-be retirees as they face inflation, volatile markets and a lack of pensions, John said.

Changing your mindset is crucial

Certified financial planner Kyle Newell reminds clients that the savings they worked so hard to amass is there to help them live well in retirement.

“I tell them, now the money is doing the work [so] they don’t have to. That seems to help people,” said Newell, who runs projections for his clients to help them see if they can afford to spend a little more than they may assume.

For clients who are fixated on having the same amount of money or more when they die, CFP David Edmisten asks them a simple question: Why is that important to you?

“I try to ask them what’s the purpose of the money: To have it? Or to use it as a tool to do what you want and to avoid what you don’t want?”

He also asks them to think about what they really want to accomplish and to view their savings as the means to that end. “A lot more time needs to be spent thinking about purpose in retirement. Those who know what their purpose is and what they want to do report being more satisfied,” Edmisten said.

And he also advises clients to go easy on themselves and view their first year in retirement as a learning experience when it comes to spending.

They’re trying to figure out who they are now that their primary career is over and figuring out what they can and can’t do financially, he said. “I had a client with millions who asked me if he could buy a used car.”

Practical steps you can take

It’s hard to manage your money well in retirement unless you’re realistic about what’s on the table.

The first thing to do is to make a budget, and sketch out a plan to cover your expenses.

“You really need to know ‘What are my assets and spending patterns and how do I harmonize the two?’” John said.

So before retiring, keep track of your spending and regular expenses, like housing, food, health care, etc. Then assess how those expenses might change in retirement (e.g., if you plan to move to a less expensive home or area; and if you’ll qualify for Medicare or if your insurance costs will be subsidized by your old employer).

Account, too, for anticipated one-time outlays, such as paying for a child’s wedding, buying a car, or taking a major vacation.

Then assess what fixed income you will have coming in (e.g., Social Security or pension payments).

The difference between your expected outlays and your fixed income is the amount you will need to draw from your savings.

Once you have that number, build a cash bucket that can cover what you’ll need for a year or two so you won’t be forced to sell anything if the market heads south, or you retire into a bear market.

“A year before you retire you should have 12 to 24 months’ worth of cash,” Edmisten said. “If we get into a recession we should never have to sell a stock to meet spending needs when the market is down.”

It would also help toconsult with a professional A fee-only financial fiduciary adviser can help you strategize how to manage and use your money in the years ahead, John said.

Those on the cusp of retirement often “get like deer in the headlights,” said Edmisten, whose clients are primarily between the ages of 58 and 63 and plan to live for a time off their portfolios until Social Security and Medicare kick in. “The one common feeling I hear most is that my clients say they are overwhelmed with all the choices they need to make to live off their savings in retirement,” he said.

“With the different types of accounts many have, the potential for penalties and higher taxes if withdrawals are taken incorrectly and sorting out how their investments may need to shift for retirement income, it can be a lot for a new retiree to get their head around.”