Editor’s Note: Ian Johnson is the Stephen A. Schwarzman senior fellow for China Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. He worked for 20 years as a journalist in China, winning a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

Every decade or so, China’s political system is wrenched by change. Some of these events are headline-grabbing – the Tiananmen massacre of 1989 or the brutal crushing of the Falun Gong spiritual movement in 1999.

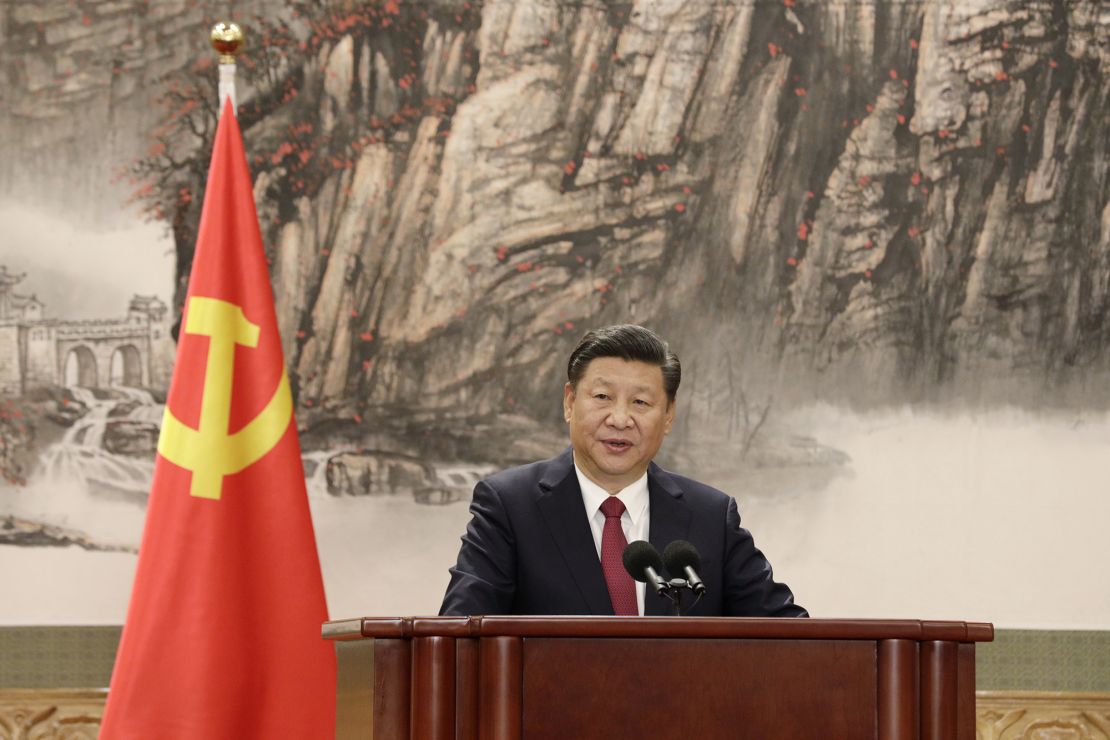

Others are more subtle, such as the eruptions of 2012, when China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, took power. That year included the toppling of a major Communist Party leader, the disgrace of a senior political adviser and the revelations that the family of the country’s beloved premier accumulated billions in wealth during his tenure.

By contrast, this year seems quiet. There are reports that Chinese leader Xi Jinping is being challenged by his premier Li Keqiang, or that he is under pressure because people are fed up with the country’s relentless zero-Covid strategy. But, even if true, these are relatively paltry cracks in the fa?ade.

And yet 2022 actually marks a huge upheaval in Chinese politics – one that we’re going to feel over the coming years. This will come in the form of clashes with democratic countries over foreign policy, a slower-growing economy and political uncertainty.

This upheaval isn’t being driven by attacks on Xi but by Xi’s own actions, which have upended a 30-year consensus over how to choose top leaders. That’s because Xi is poised next week to take an unprecedented third term in office, destroying a system put in place a generation earlier.

The evolution of China’s term limits

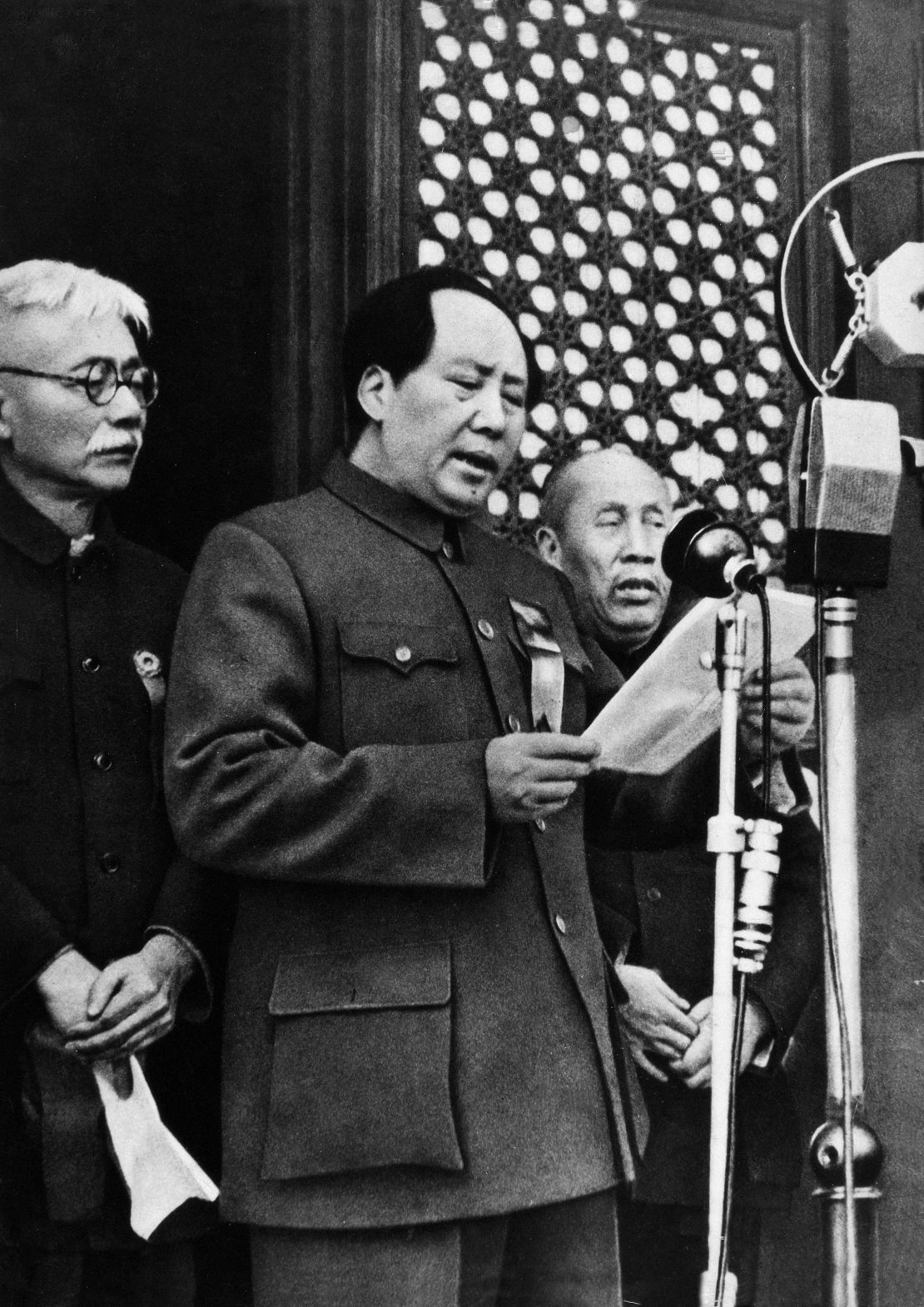

The system was meant to protect China from the turmoil of the Communists’ first decades in power. That era started with the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and lasted until the death of its first leader, Mao Zedong, in 1976.

Mao ran roughshod over other leaders, subjecting China to wild swings in policy that caused tens of millions of deaths, fomented revolution abroad, and left the country poor.

The person who took over from Mao was Deng Xiaoping. During the 1980s Deng also imposed his will on China, casting aside leaders he didn’t like. But as he approached the end of his life in the 1990s (he died in 1997), Deng set in place a system of centralized power softened by term limits.

Under Deng’s system, the top leader’s power came from holding three positions at the same time. In order of importance, they are: general secretary of the Communist Party, which meant the leader ran the political party that runs the country; chair of the Central Military Commission, meaning control of the military; and the title of “president” of China, which is a ceremonial post that means the person is head of state and thus gets a 21-gun salute abroad.

To make sure that this person didn’t abuse this immense power, Deng set up an informal rule that the person get only two five-year terms. The leader would be appointed at a Communist Party congress – a national meeting held every five years. They would then be reelected at the next party congress five years later and retire at the third.

Then along came Xi

This system worked for Deng’s two hand-picked successors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Jiang retired more or less on schedule in 2002 as did Hu in 2012.

If Xi had followed this system, he would retire at the party congress next week. Not only that but in fact we would have known his successor in 2017, just as we knew a decade earlier, in 2007, that Xi was going to succeed Hu.

Another part of Deng’s system of orderly succession was telegraphing halfway through one leader’s term who their successor would be. That was meant to forge consensus and prevent wild swings in policy.

But no successor was appointed in 2017, meaning we knew around then that Xi wanted a third term. Xi’s intentions became clearer in 2018 when China’s parliament lifted term limits on the presidency.

Even though ceremonial, the post had term limits enshrined in the constitution. Changing the constitution to lift those limits made clear that come 2022, Xi was going to go for a third term as supreme leader.

What China will look like under Xi

So in some ways what is happening this year was set in motion years earlier, but it’s still hugely significant. This will play out in ways that people around the world will experience in three important ways.

The first is in continued tension and conflict in foreign policy. Under Xi, China began projecting power beyond its borders. Under his watch, China massively built up its military presence in the South China Sea, constructed military bases in South Asia and Africa and instructed its diplomats to use very blunt, aggressive language in dealing with other countries – something known as “wolf warrior” diplomacy.

Most importantly, China took a new, harder-line approach toward Taiwan. In August, his administration released a white paper that carries a marked change in tone from previous white papers in 1993 and 2000.

Unification with Taiwan is now described as “indispensable” for Xi’s key overarching policy goal of “the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” That likely means more tensions with democratic countries over Taiwan and an increased threat of Chinese invasion.

Second is slower economic growth. Xi’s government has initiated few market-oriented reforms, leaving huge swaths of the economy still in state hands. That’s contributed to slowing economic growth during his decade in power and growing youth unemployment.

Over the past few decades, one thing that the world economy could count on was strong Chinese economic growth. That may no longer be the case.

Finally, China faces political uncertainty for the first time in decades. Even though Deng’s system lasted only a generation, it did give China a period of political stability that it hadn’t enjoyed in more than a century.

Older, not wiser

Superficially, this is still the case: Xi rules supreme, with no challenger in sight. China seems to be very, very stable.

But what of the future? Xi is 69 and cannot rule forever, but is not expected to anoint a successor at the party congress. Most analysts believe he will take a fourth term, too.

As Xi ages, and further tightens his grip, his circle of friends and advisors will inevitably shrink, as will his ability to process new information and new ideas.

We’ve already seen this in the Xi administration’s decision to blindly follow its “zero-Covid” policy, despite overwhelming evidence that it is now counter-productive. Will this sort of inability to correct course become the norm?

In this situation, it’s not out of the question to foresee a period of slow but steady decline setting in, with the leadership around Xi unwilling to engage in economic reforms or allow the sort of freewheeling intellectual life that in previous decades had allowed China to flourish.

Instead, repression is likely to continue, not only for parts of the country with large minority population, such as Xinjiang, but in the country’s ethnic Chinese heartland.

During its nearly 75 years in power, the Chinese Communist Party has shown a remarkable ability to adapt. That’s included massive course corrections, which set China on its current path to prosperity. Such changes, however, only took place during periods of crisis when the leadership was forced to make painful choices.

Next week’s party congress, however, signals the opposite: a government set to keep doing what it’s been doing for the past decade, even though the country badly needs a change.