The latest signs of the crisis New York is facing are massive white tents the city’s mayor says he never imagined he’d have to build.

The arrival of buses from the border shows no sign of slowing, and these new emergency shelters on Randall’s Island could soon house hundreds of migrants.

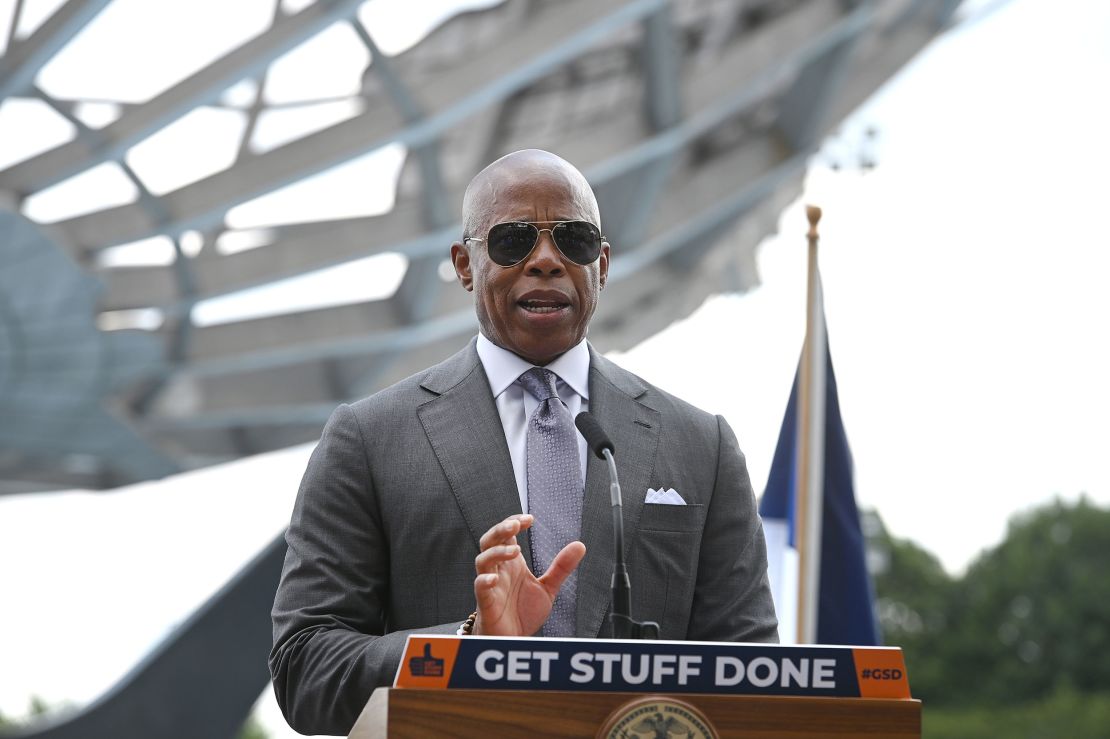

It’s been months since Texas Gov. Greg Abbott started busing migrants to New York. And it’s been just over a week since Mayor Eric Adams declared a state of emergency, warning that the growing number of new arrivals were overwhelming homeless shelters, straining resources and could end up costing the city $1 billion.

In a place that’s long prided its history as a home for immigrants, where the right to shelter is legally guaranteed, the sudden arrival of busloads of asylum seekers has forced officials to reckon with those ideals in real time.

Abbott argues he’s exposed the hypocrisy of liberal leaders who are buckling under pressure that’s a fraction of what border states like his deal with daily. Adams says his city has risen to the occasion, and that New York remains committed to helping the many arriving migrants who’ve gotten caught in the cruelty of a man-made crisis. But to do that, he says, the city needs – and deserves – more help from state and federal officials.

“This is unsustainable,” Adams said as he announced the state of emergency. “The city is going to run out of funding for other priorities.”

It’s a fast-moving situation in America’s largest city at a politically volatile moment, with midterm elections looming. Here’s a look at some of the key issues we’re watching.

A system that’s been struggling for years is now nearing a ‘breaking point’

Many of the arriving migrants have ended up in New York’s already overburdened homeless shelter system, which Adams warned last month was “nearing a breaking point.”

City officials say an increasing number of asylum seekers fueled a steep rise in the shelter population, which hit a record-setting high of more than 62,500 people last week and has kept climbing.

Adams says about one in five people in the city’s shelters are asylum seekers – and that the shelter population could continue to increase dramatically if migrants continue to arrive at the same rate.

“Though our compassion is limitless, our resources are not,” Adams said as he declared the situation an emergency last week. “Our shelter system is now operating near 100% capacity. And if these trends continue, we’ll be over 100,000 in the year to come. That’s far more than the system was ever designed to handle.”

Advocates point out that problems with the city’s shelter system have persisted for years.

“We were concerned about capacity even before there was any discussion about an influx of recent migrants,” says Kathryn Kliff, a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society’s Homeless Rights Project.

The shelter population had dipped during the pandemic, but it’s been growing steadily since April, according to city data. The arrival of more migrants in the city is one factor, Kliff says, but far from the only one.

Evictions, which have been on the rise since a pandemic moratorium ended earlier this year, are forcing many people to seek shelter, Kliff says. Others are driven by domestic violence or crushingly high housing costs, she says.

“There’s certainly an uptick in the numbers, and there’s a lot of people coming in,” she said. “It’s so difficult to afford housing in New York City, and the city has not prioritized investing in affordable housing. All of these factors are contributing to a situation where we’re reaching an all-time high in terms of the shelter census.”

According to the latest tally from New York, as of Saturday more than 19,400 asylum seekers had entered the city’s shelter system in recent months. Last week officials told CNN more than 14,100 remained in shelters.

“A lot of times people see what that system is and say, ‘This is not what I want’ and then go elsewhere,” Kliff says.

The migrants who remain, she says, are often the ones who need the most help. Advocates say many don’t have any connections with the community or idea of where to turn for help.

“By the time they get here, they have literally nothing. They’re coming with the only clothing they own,” Kliff says. “They’ve been through so much, and so much trauma, when they get here.”

Where buses to New York are coming from, and who’s on board

The Texas governor’s campaign to bus migrants north has gotten the most attention. It’s also drawn sharp criticism from Adams and others who accuse him of treating people as political pawns as Abbott, a Republican, seeks reelection.

According to the latest figures released by Abbott’s office, Texas has bused more than 3,300 migrants to New York since August 5. New York officials have said they believe busing to their city began well before August.

But Abbott’s effort isn’t the only one. The city of El Paso, Texas, which – like New York – is led by a Democratic mayor, says it’s sent about 10,000 migrants to New York City so far this year.

Many migrants also come to New York on their own with the financial assistance of nonprofits.

City officials have said most migrants arriving in New York are from South America. CNN has spoken with many asylum seekers from Venezuela among the recent arrivals.

In New York there’s a ‘right to shelter,’ even for migrants who’ve just arrived

Other large cities, including Chicago and Washington, have also seen an increasing number of migrant arrivals on buses from Texas. But there’s a key detail that sets New York apart. As a result of a series of lawsuits and consent decrees, the city is legally required to provide shelter to anyone who requests it.

“New York is unique. We have a right to shelter in a way that other places don’t. … We’re the only jurisdiction that has a right to shelter that’s enforceable by a court,” Kliff says.

The policy applies to anyone in the city, including migrants who’ve just arrived. The right was hard fought, and it’s important that migrants are included in protections, Kliff says.

Last month Adams told CNN’s Jake Tapper the city was committed to complying with it.

“We’re going to follow the law, and as well as our moral obligation and responsibilities. It is going to be challenging. We’re experiencing the challenges in doing so. But we’re obligated by law here in the city of New York. … This is a right-to-shelter city, and we’re going to fulfill our obligations,” he said.

The tents New York is building have sparked some criticism and concern

The mayor’s emergency declaration and accompanying executive order waive land-use restrictions and allow for the swift construction of emergency shelter space, like the tents erected on Randall’s Island, just east of Manhattan.

Officials say the facility, dubbed a Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center, will provide temporary respite to about 500 adult asylum seekers and is expected to open soon.

About a third of migrants arriving on buses report a desire to go to other destinations, according to Manuel Castro, commissioner of the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs.

“The humanitarian centers…will provide support for those who want to move on to other cities and states,”he recently told reporters.

The approach has faced criticism from some city council members, who argue hotels are a better option and have raised concerns about flooding and other environmental issues with possible tent shelter sites. Adams has announced the city is opening a family-focused center at a hotel in midtown-Manhattan and pushed back on criticism of the tents, calling for city council members to offer more solutions.

Kliff says the Legal Aid Society is also watching the tent effort closely to make sure it complies with right-to-shelter requirements.

“The announcements keep changing about exactly what they’re providing and how they’re providing it,” she says. “Our concern is about protecting the right to shelter and making sure asylum seekers are not in a position where they’re offered something less than what they’re entitled to.”

New York has seen large numbers of immigrants arriving before

Roughly 3 million immigrants live in New York, more than a third of the city’s population. And the city has a long history of welcoming immigrants.

Nancy Foner, a distinguished professor of sociology at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center, has studied it closely.

How do the number of recent migrants described by city officials as “unprecedented” stack up against past arrivals?

“That’s nothing,” Foner says after hearing the city’s latest statistics.

“There was probably a higher percentage of immigrants and their children in New York City in 1910-1920 than there is today. Immigrants were pouring in -— the Italians, the Irish, the Russian Jews,” she says.

More recent arrivals come from other parts of the world, she says, and there’s also another notable difference.

“The way they’re coming is unprecedented, that they’re being shipped from one part of the country to another,” she says.

How declaring this an emergency could help

That’s a big reason behind the crisis, according to Adams.

“Thousands of asylum seekers have been bused into New York City and simply dropped off without notice, coordination or care, and more are arriving every day,” he said as he announced his emergency declaration.

Camille Mackler bristled at first when she heard the mayor declare a state of emergency. To her, his words flew in the face of months of welcoming efforts.

“We’ve shown that we can welcome differently. And I think we should also be able to talk about it differently. … New York has shown that we don’t need to treat these individuals as a danger. They’re not a threat,” says Mackler, executive director of Immigrant ARC, which represents legal service providers.

“They’re coming here. They need help. They need assistance. We know that if we provide it for them, they will make New York home and we’ll be the better for it.”

But she said she understands there are strategic reasons behind the mayor’s move.

“I do understand from a tactical perspective that a state of emergency declaration frees up funds and allows the administration to pursue potentially other sources of funding, and to put more pressure on the state and federal government to provide more support,” she said.

What a new Biden administration border policy could mean

The thousands of asylum seekers who’ve arrived in New York in recent months are just a fraction of the more than half a million migrants in the 2022 fiscal year who were apprehended at the US southern border, processed and released by authorities while their immigration cases proceed, according to US Customs and Border Protection.

A CNN analysis earlier this month found that migrants from three countries – Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba – were driving a spike in encounters at the southern border.

Days later, the Biden administration announced that authorities would start sending Venezuelans who are apprehended at the border back into Mexico, while also creating a legal pathway and screening process for 24,000 Venezuelans with US ties to enter the country at ports of entry.

The move sparked a swift chorus of criticism from immigrant rights groups, who argue that the administration’s announcement that it had reached a deal with Mexican authorities and will now use the Title 42 public health measure against Venezuelans is unjust and dangerous.

If it’s applied as rigidly to Venezuelan migrants as the Biden administration has vowed it will be, the policy could significantly decrease the number of migrants who are released into the United States after crossing the border. That could also mean less migrants end up making the trek to New York.

Adams praised the move in a statement, calling it a “short-term step to address this humanitarian crisis and humanely manage the flow of border crossings.” But he said he’s still hoping to get more help from Washington, including “Congress both passing legislation that will allow asylum seekers to legally work and providing emergency financial relief for our city.”

So far, the city is still waiting for that emergency federal funding. And buses of migrants keep arriving.

CNN’s Priya Krishnakumar, Ray Sanchez, Samantha Beech, Rosa Flores, Athena Jones and Gloria Pazmino contributed to this report.