Americans and Britons once smugly viewed political uprisings, governing meltdowns and self-defeating errors as the eruptions of unstable countries and immature political systems.

No longer. And China and Russia couldn’t be happier.

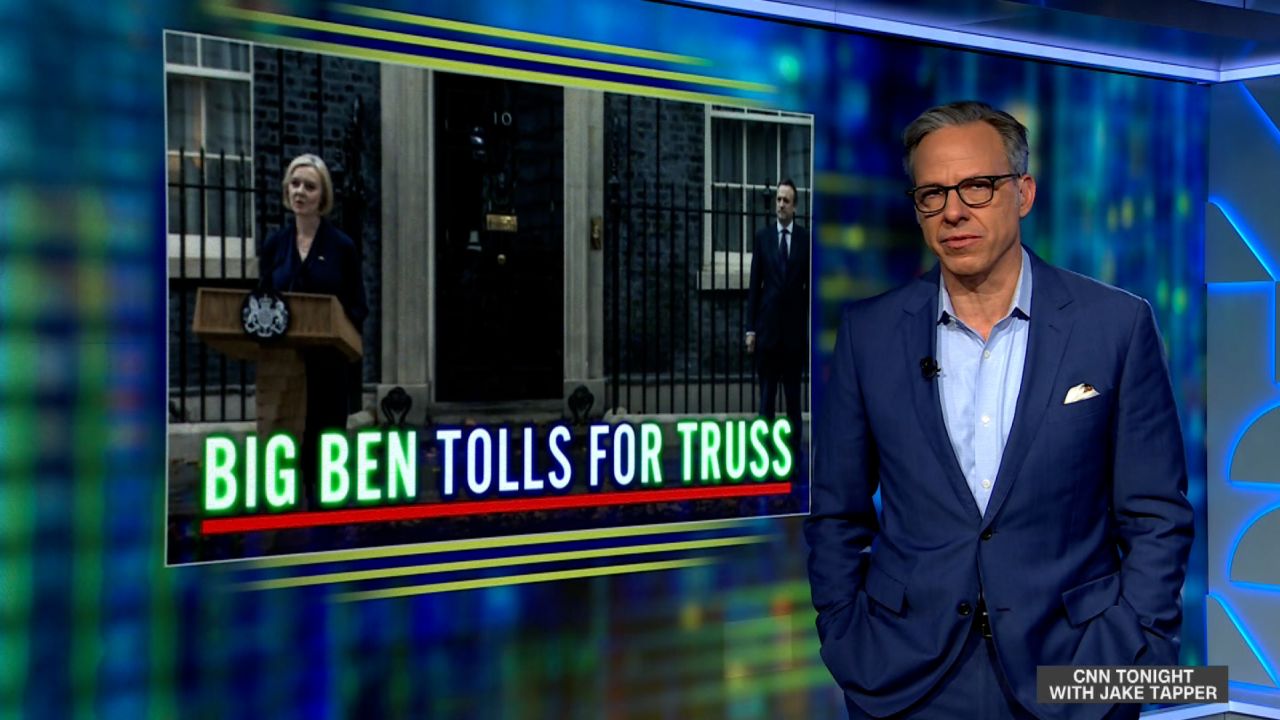

The humiliating resignation of British Prime Minister Liz Truss after just 45 days in power on Thursday was just the latest governing fiasco to rock the two great democracies on either side of the Atlantic.

Britain has reeled from crisis to crisis in recent years in a way that has left allies who once viewed the country as an exemplar of good governance baffled at its self-immolation. This has occurred as the United States, the global anchor of democracy and capitalism, has gone through its own paroxysms, including an insurrection, and intensifying assaults on its free elections.

Both nations, which had saved the world for democracy in World War II, were left reeling by fractious leaders, who often disdained truth and fact and built power bases by stoking resentment from the detritus of inequality brewed by globalization. These leaders mocked experts, declared blood feuds with governing establishments and civil service functionaries and conjured an often mythical vision of past glories with a vow to make their nations great again.

In the United States, the political rise of Donald Trump left his country internally estranged, turned the world’s most vital democracy against its allies and left democratic decay in which the presidency of Joe Biden may just be an interregnum. In the United Kingdom, the Brexit vote to leave the European Union led by Boris Johnson left the country unmoored and poorer than before, ushering in an era of political madness about to produce a fourth prime minister in about three years.

Notwithstanding their poisoned legacies and chaotic lie-strewn administrations, both Trump and Johnson are mulling comebacks, showing that this wild period of rule breaking and personality-driven populism is far from over and that more conventional leaders are still failing to satisfy voters and restore faith in effective government.

The chaos in London and Washington has dangerous consequences. The health of Britain and the United States are critical to the entire Western way of life.

The self-ravaging of Western democracy is coming at a moment when it is under an intense challenge from powerful foes. Russian President Vladimir Putin meddled in the US election in 2016 in an effort to devalue the prestige of the Western political model. While his own leadership has been disastrously exposed by the war in Ukraine, Russia can only benefit from the assaults on the US electoral system and governing incoherence in the UK that are damaging democracy’s brand worldwide.

The crisis of confidence of the two great English-speaking democracies is also coming as an increasingly mighty and aggressive China seeks to challenge the Western-led global order set up after World War II. With President Xi Jinping expected to lock in an unprecedented third term in modern times in the next few days, Beijing is increasingly touting its brand of ruthless one-party capitalism as an alternative model to the open, democratic market economics of the West.

Biden warned on Thursday that allies were watching what was happening to America’s political system, citing the January 6, 2021, insurrection and a Republican response that downplayed Trump’s role in inciting the riot.

“These guys on the other team don’t get it. They don’t get it that how America does is going to determine how the rest of the world does,” Biden said at a fundraiser in Philadelphia, according to the White House press pool.

“They look to us as a leader. They look to us … because they’re not as big or as powerful.”

A prime minister’s staggering miscalculation

Here’s the most extraordinary feature of Truss’ tenure in 10 Downing Street: she decided that a kingdom at risk of coming apart, facing a winter inflation and energy crisis caused by a European war and a once-in-a-century pandemic, and that had just lost the only monarch most of its people had known, didn’t need a period of stability.

Her sudden new budget featuring massive tax cuts for the rich, with no plan to pay for them, alarmed the markets, crashed the pound, almost destroyed the pensions industry and left homeowners facing huge rises in mortgage payments.

The move, possibly the most disastrous political gamble in Britain since the 1950s Suez Crisis, trashed London’s reputation for sound financial management and reasonable governance and earned a rebuke from the International Monetary Fund. It cemented Britain’s bewildering new image as a nation locked into a repeating cycle of self-harm.

Truss was forced to withdraw the scheme, and finally resigned after several days of being in government but not power. Conservative members of parliament – scared of calling the general election the country needs because they’d be wiped out – must now select yet another two candidates for prime minister to put to the party membership, a tiny bloc of Britons who are far to the right of most of their compatriots. It is a farcical spectacle that has now been exposed as a deeply undemocratic way to choose a prime minister who can turn the nation’s direction on a dime – or a 10 pence piece.

In a way, the struggles of Conservative Party prime ministers to govern mirrors some political dynamics in the United States. Just as the Republican Party is hostage to a radical, far-right base that has fractured its reputation for sensible government, Conservative leaders have tended to appease their own extreme radicals on the right – and their visceral hostility to the European Union in particular.

At one time, Britons used to view Italy – with its notoriously unstable politics, economic crises and revolving door for prime ministers – as a punchline. But now their country’s ungovernable, faction-based politics is mocked. There’s also great concern among allies perturbed by an erratic few years in which the London government has often lashed out at its partners.

French President Emmanuel Macron, weeks after Truss equivocated over whether he was a friend or a foe of Britain, said he had one wish regarding the political blood-letting across the English Channel.

“Personally, I am always sad to see a colleague leave, but what I want is to see this stability return as soon as possible,” Macron told reporters on Thursday.

Ireland also expressed concern over how the disruption could impact its prospects after a period in which Truss threatened to trigger a trade war with Europe by tearing up a post-Brexit deal concerning Northern Ireland that the Conservative government had negotiated under Johnson.

“What’s important as Britain’s nearest neighbor – we have significant economic relationship and many other relationships with the United Kingdom – I think stability is very important,” Irish Prime Minister Micheál Martin said.

It was often said that Truss was facing the most difficult inheritance of any British prime minister since Winston Churchill. Her successor, due to be installed next week, will have it even worse thanks to the mayhem she triggered in what is set to be the shortest tenure of any prime minister in British history.

The question now is whether that new leader will be able to stabilize the country amid a likely grim winter of soaring heating costs, raging inflation and widening industrial strikes. Or whether he or she will subject a reeling country to yet more political bedlam caused by the fanaticism and fratricide ripping apart the Conservative Party whose long periods of power meant it was once regarded as the most successful political party in the world.

Biden can’t guarantee democracy’s future at home

Biden’s response to the Truss resignation was a brief statement that was apt given he had only met the outgoing prime minister officially once, had shown little regard for her style of government and hostility toward his ancestral home Ireland and is now preparing for the third British leader of his presidency.

“The United States and the United Kingdom are strong Allies and enduring friends — and that fact will never change,” Biden said in a written statement.

While Trump egged on Brexit and delighted in London’s feud with the EU under the Conservatives, the Biden and Obama White Houses regarded the political madness that engulfed the UK – and the consequent diminishing of the global diplomatic weight of America’s special relationship partner – with some dismay. Obama caused a huge controversy when he warned during a visit to London that the UK would go to “the back of the queue” for a trade deal with the US if it left the EU. His comment might have infuriated pro-Brexit leaders but it did turn out to be accurate.

On the question of whom the US calls when it wants to talk to Europe (a possibly apocryphal comment often attributed to former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger) the answer is that 10 Downing Street is no longer on the top of the White House speed dial. While the US and the UK could still hardly be closer in military and intelligence matters, Washington – at least when Trump was out of the Oval Office – long looked to former German Chancellor Angela Merkel as its most important European leader. Now that she’s retired, Macron is the main point of contact. Biden sent an unmistakable signal of the just-reelected French leader’s rising global role with an invitation to his first state dinner in December.

Both leaders have publicly warned of the threat to global and western democracies. Macron beat off a challenge from far-right leader Marine Le Pen in winning reelection this year, but her party’s influence is only growing. Macron told CNN’s Jake Tapper in an interview last month, “I think we have a big crisis of democracies, of what I would call liberal democracies.” Asked whether he was concerned about democracy in America, he said: “I worry about all of us.”

When Biden took office in the wake of Trump’s unprecedented attempted disruption of a peaceful transfer of power at the Capitol, which still bore the scars of its ransacking by the former President’s mob, he put saving global democracy at the center of his term.

He returned to the theme last month outside Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where the American experiment was born. He tacitly admitted that while he was warning the world about the danger democracy faces abroad, he could not even guarantee its survival at home.

But he told Americans: “It is within our power, it’s in our hands – yours and mine – to stop the assault on American democracy.”

He added: “I believe America is at an inflection point – one of those moments that determine the shape of everything that’s to come after.”

Yet this midterm election has only stressed the peril ahead. Scores of 2020 election deniers are running for office as Republican nominees. The ex-President’s falsehoods have convinced millions that the country’s elections are corrupt. The “Make America Great Again” movement is more wedded to the authoritarian personality cult of its leader than ever as Trump considers a run for a new presidential term that would likely tear at the foundation of democratic governance more than the first.

While it’s possible perhaps to perversely argue that British democracy worked in quickly dispatching a failed leader in Truss, Trump has been impeached twice, is facing multiple legal challenges and is still a viable political figure with a real chance of returning to power. This is why when Biden tells foreign leaders that “America is back,” many of them clearly wonder for how long.

While leaders rise and fade, the enduring strength of the political systems in the US and the UK has been their stability, ordered transfers of power and their ability to foster conditions in which capitalism can thrive and people can move up the income ladder.

On both sides of the Atlantic, this foundation is now in doubt.