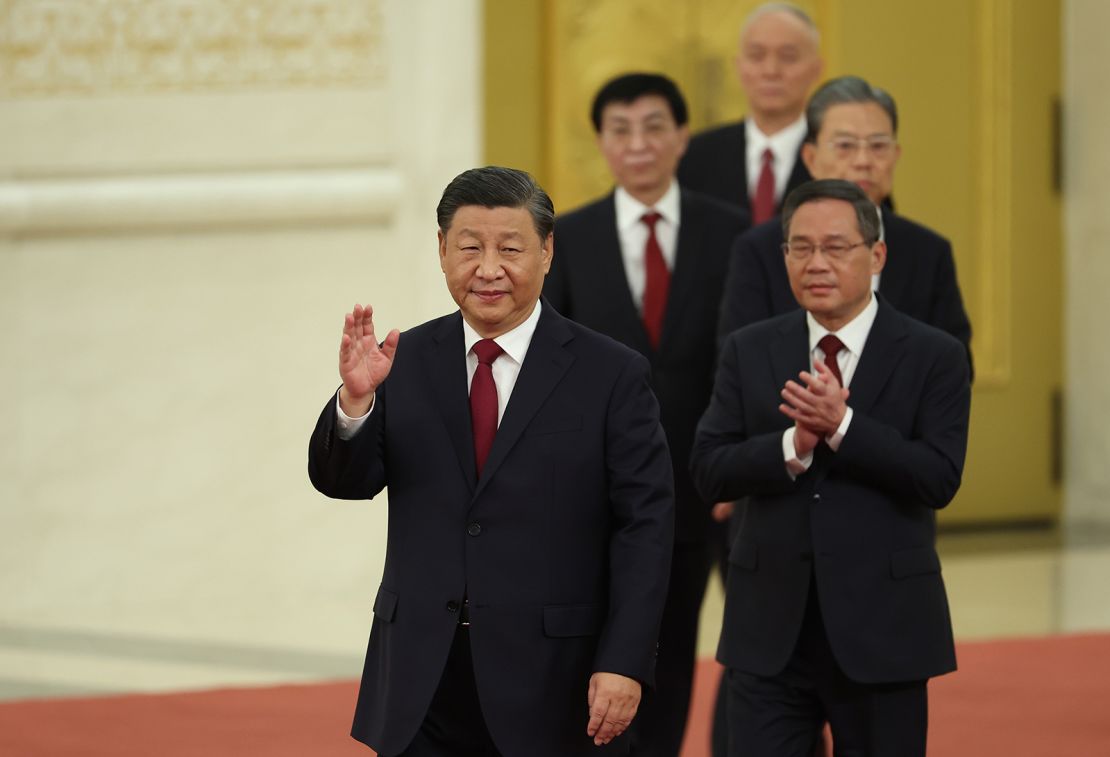

When Chinese leader Xi Jinping secured a historic third term in power at the weekend and stacked his top team with loyalists in a clean sweep not seen since the Mao era, investors were quick to pass judgment.

Chinese stocks listed in Hong Kong and New York crashed on Monday, and the yuan hit its lowest level against the US dollar in nearly 15 years a day later. On offshore markets, the Chinese currency traded at its weakest point since data provider Refinitiv began keeping records in 2010.

Xi’s preference for personal loyalty over technocratic competence bodes ill for China’s already bleak economic outlook, analysts said. Replacingseasoned economic officialswith people with much less experience also signals a more ideology-driven policy that could further dent private sector growth and worsen Beijing’s ties with the United States, they added.

“The market is clearly disappointed by the new seven-man Politburo Standing Committee which is filled with Xi’s allies,” said Lilian Co, who manages the Strategic China Panda Fund at Eric Sturdza Investments.

“Since Xi’s ideology has not been market-friendly in the last few years, a leadership team loyal to Xi means no change in policy direction as long as he is in power,” she said.

The yuan rebounded slightly on Wednesday, and stocks were also modestly higher, following coordinated statements late Tuesday from the Chinese central bank and various financial regulators that they would maintain the stability of the currency, Chinese markets and the financial system. But there was little sign of enthusiasm in markets.

Missing from the new leadership teamare senior officials who have backed market reforms and opening up the economy. Those pushed aside included Premier Li Keqiang, Vice Premier Liu He, and central bank governor Yi Gang.

Investors fear that Xi’s tightening grip on power will mean the continuation of policies such as the zero-Covid strategy and crackdown on the private sector that have already caused serious damage to the world’s second-biggest economy.

Analysts are also concerned that the removal of reformists from the leadership of the Communist Party means no one will dare to tell Xi he is wrong if his policy agenda fails.

“The fact that Xi broke with a long tradition of having members of both party wings represented on China’s highest political committee sets the stage for a leadership style that prioritizes personal loyalties over competence and productive discourse,” said Sonja Opper, a professor at Bocconi University and an expert on the Chinese economy.

“In effect, Xi Jinping establishes an echo chamber around his own ideas,” she said. “The risk is that China’s leadership becomes isolated and loses sight of alternative, possibly better ways to approach the many challenges the country faces.”

Frequent Covid lockdowns have hampered consumer spending, disrupted supply chains, and caused massive job losses. The country’s once vibrant private sector is suffocating under Xi’s “common prosperity” campaign. A persistent real estate slump and a weakening global economy have compounded the problems.

The World Bank recently slashed its forecast for China’s growth to 2.8% in 2022, the first time it projected the Chinese economy to fall behind the rest of Asia since 1990. Beijing’s official target is 5.5% growth for this year.

Analysts say that if Xi closes the dooronmarket liberalization, policies could increasingly be driven by ideology, which would further hurt private industry and worsen US-China tensions.

“Xi’s vision is nothing short of a new ideology-infused economic order,” said Craig Singleton, senior China fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a DC-based think tank.

The extension of his tenure just locks in China’s current economic orientation — one that is “unabashedly hostile” to free market forces, he said.

Xi’s announcement last week that China’s definition of national security should be expanded to include at least 16 different areas — including military, territorial, technological, economic, food, energy, resources, and supply chains — will further complicate matters.

“These economic issues cut across key facets of the US-China relationship, which means that deteriorating ties will not be limited to traditional cleavage points, such as Taiwan or the South China Sea,” Singleton added.

Li Qiang in, Li Keqiang out

The personnel changes have also been remarkable.

Li Qiang, the party boss of Shanghai who presided over the city’s chaotic two-month lockdown, is now the second-highest ranking party official after Xi. That puts him in line to succeed Premier Li Keqiang when he steps down in March. He will be faced with the task of managing thenearly $18 trillion economy.

Li , 63, would be the first premier since the Mao era not to have previously worked in the State Council — China’s cabinet — as vice premier, analysts pointed out.

“Li doesn’t have any central government experience at all,” said Julian Evans-Pritchard, senior China economist at Capital Economics. “And his track record at the local level is hardly perfect — he bungled Shanghai’s initial response to the Omicron wave earlier this year.”

His appointment over more qualified candidates is a clear example that “official promotion has become less meritocratic under Xi,” with loyalty and personal ties increasingly taking precedence over bureaucratic credentials, he added.

Liu He out, He Lifeng in

Just as noteworthy are those who were pushed aside.

Liu He, who led negotiations with the United States during the trade war in 2018 and 2019, lost his seaton the 205-member Central Committee of the party.

“[His]departure means the loss of one of China’s few foreign-educated and reform-minded economists in a top leadership position,” Evans-Pritchard also said.

Liu was seen by many as “a bridge between the East and West, and someone who understood the value of the market and the private sector,” said Singleton.

The man tipped to replace Liu as the Vice Premier for economic affairs is He Lifeng, head of the National Development and Reform Commission and a new face on the 24-member Politburo. The NDRC is China’s top economic planner, responsible for drafting the country’s economic plans and overseeing major state investment projects.

“Although He Lifeng is an academically trained economist, much like Liu He, his track record suggests he is likely to favor a more statist approach to economic management,” Evans-Pritchard said.

Exacerbating China’s problems?

It remains to be seen who will take the top economic jobs until official announcements are made in March. But given how the leadership reshuffle has played out so far, analysts are worried that loyal but less competent individuals could be chosen.

“The quality of policy making has suffered in recent years as officials have become increasingly focused on displays of loyalty and less on good governance and economic performance,” said Evans-Pritchard.

“This trend may get even worse now that Xi has surrounded himself with ‘yes’ men,” he added.

Xi’s consolidation of power risks undermining productivity and growth, rather than boosting it as he hoped.

“In Xi now closing the door on market liberalization, US companies and particularly US financial services companies may need to reconsider current and future investments in China, which could only further exacerbate the many serious economic challenges facing the country,” Singleton said.

![China's President Xi Jinping (R) sits beside Premier Li Keqiang (L) as former president Hu Jintao is assisted to leave from the closing ceremony of the 20th Chinese Communist Party's Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October 22, 2022. (Photo by Noel CELIS / AFP) / The erroneous mention[s] appearing in the metadata of this photo by Noel CELIS has been modified in AFP systems in the following manner: [clarifying caption to state China's former president Hu Jintao is assisted to leave from the closing ceremony] instead of [being assisted to his seat]. Please immediately remove the erroneous mention[s] from all your online services and delete it (them) from your servers. If you have been authorized by AFP to distribute it (them) to third parties, please ensure that the same actions are carried out by them. Failure to promptly comply with these instructions will entail liability on your part for any continued or post notification usage. Therefore we thank you very much for all your attention and prompt action. We are sorry for the inconvenience this notification may cause and remain at your disposal for any further information you may require. (Photo by NOEL CELIS/AFP via Getty Images)](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/221022010115-01-cpc-hu-jintao-102222.jpg?c=16x9&q=w_1280,c_fill)