Chief Justice John Roberts has at times staked out the middle ground on the conservative-dominated Supreme Court – as in June when he tried to prevent the majority from completely overturning federal abortion rights. But when it comes to race and such issues as school integration and redistricting, Roberts has been unyielding in decrying, the “sordid business, this divvying us up by race.”

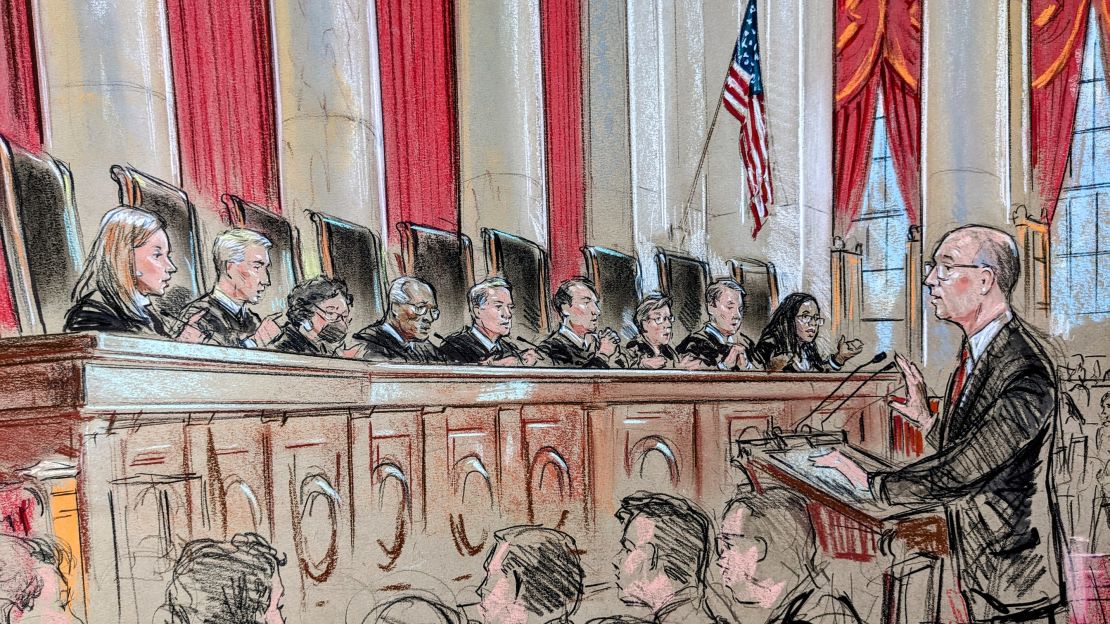

That was the John Roberts on the elevated bench Monday, as the justices heard nearly five hours of tense arguments over affirmative action.

The chief justice repeated his enduring view that race should not matter, and he denounced admissions practices that consider students’ race or ethnicity for campus diversity. He suggested that if the court were to uphold the current policies at Harvard University and University of North Carolina, racial affirmative action would never end.

“Your position is that race matters because it’s necessary for diversity, which is necessary for the sort of education you want,” he told North Carolina state solicitor general Ryan Park, who was defending the UNC program. “It’s not going to stop mattering at some particular point; you’re always going to have to look at race because you say race matters to give us the necessary diversity.”

Based on comments from his fellow conservatives, it is likely that Roberts will claim a majority of the justices. Such a win would demonstrate the force of the 67-year-old chief’s views and his grip on the court. He lost control last June in the biggest case of the 2021-22 session, when the five colleagues to his right rejected pleas to go slower to eliminate abortion protections and rolled back nearly a half century of women’s privacy rights.

That reversal of the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling continues to reverberate throughout America, from intimate family choices to political trends as the midterm elections approach. The dissolution of decades-old precedent shattered public expectations, and the country could see a replay if the conservative majority decides to discard the 1978 precedent that first allowed colleges and universities to consider students’ race, along with other criteria, to enhance campus diversity and the educational experience.

RELATED: The inside story of how John Roberts failed to save abortion rights

Lawyers for the universities, backed by the Biden administration, warned that campuses nationwide could be transformed if the challengers prevail.

US Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar implored the justices to “focus on the profound consequences of the court’s decision here for the nation that we are and the nation that we aspire to be,” as the justices neared the end of their marathon hearing Monday.

“A blanket ban on race-conscious admissions would cause racial diversity to plummet at many of our nation’s leading educational institutions,” Prelogar said from the lectern in the well of the courtroom, directly below Roberts. “Race-neutral alternatives right now can’t make up the difference, so all students at those schools would be denied the benefits of learning in a diverse educational environment and because college is the training ground for America’s future leaders, the negative consequences would have reverberations throughout just about every important institution in America.”

The paired cases, from the storied Ivy League campus and a state school founded in the 18th century, are two of the most closely watched this session. The courtroom was crowded, with extra chairs lining the alcoves. Roberts’ wife, Jane Sullivan Roberts, was among the spouses watching from a section reserved for the justices’ guests.

Students for Fair Admissions, a group established by conservative activist Edward Blum, has asked the justices to reverse a 1978 landmark that first endorsed the use of race in admissions, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, and the 2003 decision, Grutter v. Bollinger, that affirmed it.

The claims brought by Students for Fair Admissions fall under the 14th Amendment guarantee of equal protection of the law and under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which forbids private schools that receive federal funds from discriminating on the basis of race.

The controversy animated Roberts, himself a graduate of Harvard College and Law School.

“Take two African American applicants,” he said to lawyer Seth Waxman, representing Harvard. “They both can get a tip, right, based on their race? And yet they may have entirely different views. Some of their views may contribute to diversity from the perspective of Asians or Whites. Some of them may not. And yet it’s true that they’re eligible for the same increase in the opportunities for admission based solely on their skin color?”

Waxman acknowledged that being an African American or being a Hispanic could give the applicant a boost and may even be determinative of who gets a coveted place in the freshman class.

“Race, for some highly qualified applicants can be the determinative factor, just as being, you know, an oboe player in a year in which the Harvard-Radcliffe orchestra needs an oboe player will be the tip,” Waxman said, offering an example that Roberts immediately skewered.

“We did not fight a Civil War about oboe players,” he rejoined. “We did fight a Civil War to eliminate racial discrimination, and that’s why it’s a matter of considerable concern.”

A belief that civil rights measures of the 1960s and 1970s have run their course

Roberts grew up in Long Beach, Indiana, where his father was an executive at Bethlehem Steel plant. After graduating from a Catholic boarding school in the state, he attended Harvard. He finished college in three years and headed across the Cambridge campus to law school.

His public views on race date to his early 1980s tenure as a lawyer in the Reagan administration, advocating for a “colorblind” approach, whether in remedies for voting-rights violations or lingering discrimination in public schools.

RELATED: ‘The Chief’: John Roberts’ journey from ‘sober puss’ to the pinnacle of American law

Roberts brought that perspective to the bench, when he was appointed by former President George W. Bush in 2005 as chief justice.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Roberts wrote in a 2007 case as the majority invalidated school integration plans from Seattle and Louisville. School districts had devised the plans to try to offset contemporary school segregation caused by Whites and Blacks living in distinct parts of a city.

A year earlier, in a voting rights case, Roberts referred memorably to the “sordid business” of “divvying” residents by race, as states attempted to compensate for past discrimination against Black and Hispanic voters.

Perhaps it has been the area of voting rights where Roberts has made his greatest mark. In 2013, he led a narrow majority to strike down a provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act covering certain states with a history of discrimination, mainly in the South.

“Our country has changed, and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions,” the chief justice wrote in 2013.

Roberts’ outlook appears to stem from a belief that civil rights measures of the 1960s and 1970s are no longer needed, and, in some respects, may have been misguided from the start.

On Monday, Roberts challenged the core notion that Blacks or any other students can be classified based on their race, given differences in individual experiences.

“There’s been a lot of talk about African American applicants to Harvard in sort of a general, indistinguishable way when, in fact, they cover a very broad swath of applicants,” he said. As an example, Roberts referred to a hypothetical Black student applicant who “grew up in Grosse Point, had a great upbringing, comfortable, his parents went to Harvard, he’s a legacy, and yet, under your system, when he checks African American, he gets a tip. He gets a benefit from that.”

“It is simply not the case that every Black applicant gets a tip,” Waxman protested.

Appearing to align with the chief justice were Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

On the other side for much of the give-and-take were the three liberal Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. (Jackson participated only in the UNC case; she has recused herself from the Harvard dispute because she previously served on its board of overseers.)

The justices on the left spoke expansively about the educational experience. “I thought that part of what it meant to be an American and to believe in American pluralism,” Kagan said, “is that, actually, our institutions are reflective of who we are as a people in all our variety.”

Roberts had a separate concern regarding the educational setting, where he said race “permeates.”

Students arriving on campus, he said, “get the message, from the beginning, that race counts.”