It’s not unusual for temperatures in India’s Thar Desert to reach 48 degrees Celsius (118 degrees Fahrenheit). Even when they drop, hot winds sweep across the bare plains. The soil here is infertile, water is scarce. This place is near unlivable for humans – but it’s ideal for one of the world’s biggest solar farms.

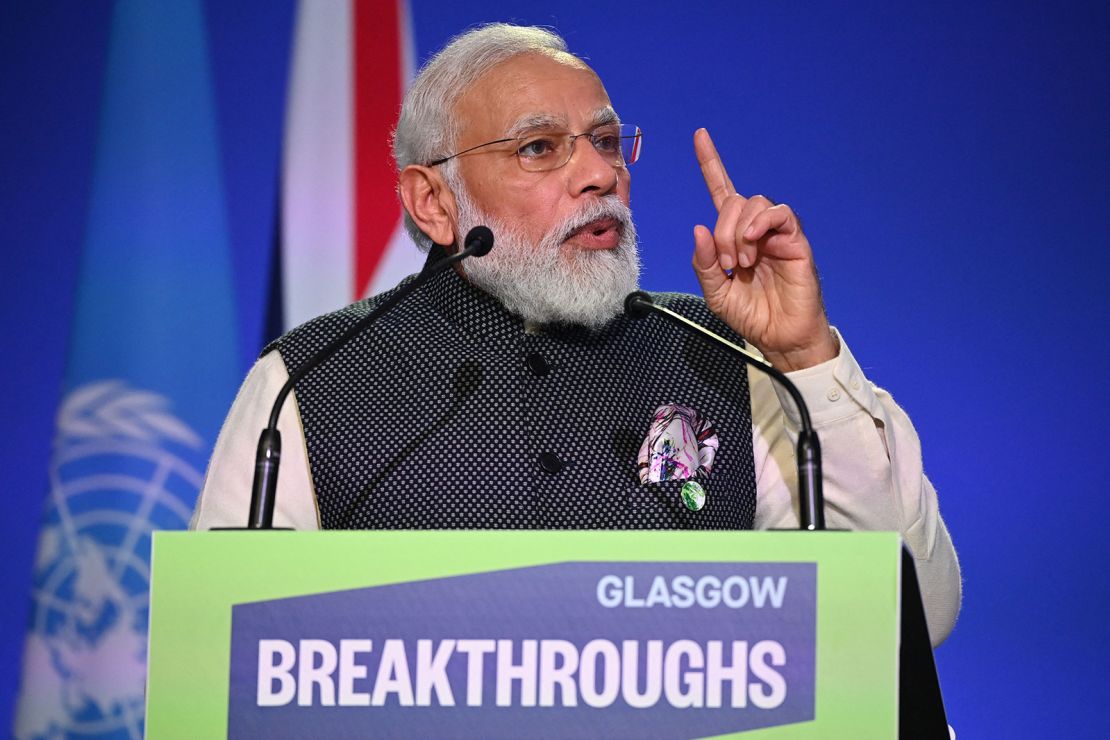

The Bhadla Solar Park in Rajasthan state, near India’s border with Pakistan, is a symbol of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s gargantuan ambitions to transform his nation into a green energy powerhouse. By 2030, Modi wants half of India’s energy to come from renewables.

It’s a huge and admirable goal from the world’s third-biggest carbon emitter, but achieving it will require trillions of dollars and some tough decisions by Modi.

While renewable energy is growing faster in India than in any other major economy, the country remains reliant on coal, which has long powered the country’s growth and accounts for more than 80% of its energy mix. Indian officials have also said the country plans to expand its use of the fossil fuel even as many of its nearly 1.4 billion people choke on the pollution it causes.

In the past, India has defended its use of planet-warming fossil fuels in the name of development – a stance that has seen it criticized at international climate talks.

At last year’s COP26 negotiations in Glasgow, Scotland, India led a last-minute objection to language in a proposed joint statementaround phasing out coal. Its chief delegate argued government fossil fuel subsidies to the public must continue – how else could India get fuel like natural gas to poor people who are still burning wood to cook their meals, he asked.

That exchange highlights the contradiction at the heart of India’s stance on climate change – that Modi’s government can continue to set lofty goals, but when it comes to realizing them, his country is caught in a Catch-22 between development and decarbonization.

India’s Power Minister Raj Kumar Singh demonstrated that dilemma in September when he announced plans to add 56 gigawatts of coal power to India’s energy mix by 2030 while also investing in renewable energy – emphasizing the need to prioritize reliable power for growth.

That’s bad news for the global fight against climate change, where India’s actions have widespread ramifications.

India emits over 2.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) a year based on data collected by the EU. An analysis of its plans by the Climate Action Tracker show that the country’s goals are “critically insufficient” to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above levels before industrialization. Warming beyond that threshold will trigger irreversible damage and push many ecosystems to tipping points, climate science shows.

“As one of the world’s largest emitters, what India does is crucial for the world to meet the 1.5?C limit,” said Hannah Fekete, co-founder of NewClimate Institute who has over a decade of experience quantifying the impact of policies on emissions.

And nowhere are the contradictions in India’s stance clearer than in Rajasthan. The state is fast becoming a hotbed of solar energy, yet is also home to at least seven coal-fired power plants.

Just 400 miles from the Bhadla Solar Park sit four of the world’s five most polluted cities, according to the 2021 World Air Quality Report. On any given day, they are blanketed in the grey soot and ash of burned coal.

A global problem with individual consequences

According to a report on Climate Change in the Indian Mind from Yale University’s School of the Environment, 81% of Indians surveyed were worried about global warming, with 50% saying they were “very worried.” In addition, 64% say their government “should be doing more to address global warming.”

Still, few would claim climate change is a problem for India alone to solve. Indeed, the picture changes substantially when its emissions are seen in the context of its massive population. Per capita figures show that Indian people actually contribute relatively very little to the problem. While the average American emits 14.7 tons of CO2 a year, an Indian person emits around 1.8.

However, despite the low level of per capita emissions, the weight of the country’s struggles can be disproportionately felt on an individual level.

In Delhi, the world’s fourth most polluted city, people are seeing first-hand the impacts of the country’s coal consumption.

Resident Rohit Sharma, 36, told CNN, “We are frustrated when we look at other cities where there is not much pollution and the lives that they are able to live but we cannot.”

“The air pollution is going to impact everything,” he added. “We will have health issues, breathing issues and our life span will be cut short.”

His colleague Kunal Sharma, 28, worries about what life could look like in coming years. “If no concrete action is taken, life after 10 years is going to become extremely difficult,” Sharma said. “What can we do? We have to live here.”

The Modi government has been encouraging Indians to live more sustainably – in October launching a program that urged drivers to turn off their engines at red traffic lights and for people to take the stairs instead of the lift.

But the question isn’t just whether the world can count on the Indian public to decarbonize – it’s also about whether Indians can count on their government to do so, too.

A costly choice

Even as much of the world came to a standstill during the Covid-19 pandemic, India kept ramping up its renewables. Between 2019 and 2021, the share of India’s energy that comes from renewables increased by almost 3%, according to a 2022 report from the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi.

India has had “a sustained increase in renewable energy installation,” Nandini Das, an energy research and policy analyst at the research institute Climate Analytics, told CNN. “Even during Covid it hasn’t stopped.”

At COP26, Modi outlined a series of targets for India’s efforts to combat climate change. He pledged that by 2030, India would have increased its non-fossil fuel energy capacity to 500 gigawatts – from 156.83 in 2021 – and would be using renewable energy sources to meet 50% of its energy needs.

Experts say India is on track to meet Modi’s non-fossil fuel target by increasing nuclear energy and hydropower, but the country’s shorter-term goals – such as having 175 gigawatts of renewable energy installed by the end of 2022, enough to power up to 131 million homes – hang in the balance.

A report by S&P Global earlier this year said India may not meet its 2022 target, partly because the country still lacks a clear commitment to phasing out coal.

It’s also a question of funding – investing in renewable energy and other climate change mitigation efforts is expensive.

The developed world was supposed to be providing $100 billion a year to developing nations to help them slash their emissions and adapt to the climate crisis. That goal has never been met.

It’s money India could use. To achieve just its wind and solar targets for 2030 would cost $223 billion, according to a BloombergNEF analysis. And in the 2019-2020 financial year, India raised only a quarter of the funds needed annually to meet its initial climate goals, according to a report published by Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), an independent, non-profit research group.

If India doesn’t receive the financial support it needs, maintaining its pace on developing renewable energy will be difficult. Increasing it will be even harder.

In Rajasthan, projects like the Bhadla Solar Park have helped the state exceed its renewables goals, but experts say that success isn’t happening widely enough.

“If India sticks to its current approach, which includes expanding coal-fired power generation and infrastructure to increasingly use imported LNG, it risks massive stranded assets in the fossil energy sector and an increased dependence on energy imports,” Fekete, from the NewClimate Institute, told CNN.

“India should instead focus fully on renewable energy, with international support as needed.”

She says it if it doesn’t, India’s greenhouse gas emissions are set to increase by 2030, which will make global targets even harder, if not impossible, to reach.

“Given the size of India, this puts the global temperature goal of 1.5°C at risk,” Fekete said.

Swati Gupta contributed reporting.