When Russian forces invaded their country in late February, Vladimir Bespalov and Maria Bespalaya feared their long-held dream of starting a family through adoption was over.

“I remember that morning of February 24, very clearly,” said Vladimir Bespalov, a 27-year-old railroad worker, of the first day of the war. “We thought we were too late. We realized we were already in a state of war, and we thought we could no longer adopt.”

Instead, the situation pushed the couple to try to do it sooner, he said. “We were waiting to earn more money, have a better car, buy a house, and build something to give our children first. But when the war started, we thought why not adopt a child now and accomplish these things together as a family.”

That day, the married couple, who were living in eastern Ukraine, posted an appeal on social media.

“We want to adopt any boy or girl, any newborn or child,” it read.

Weeks later that message would reach a volunteer helping those fleeing Mariupol, a southern city that became emblematic of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ruthless campaign to take Ukrainian land, no matter the cost.

Residents were forced underground for weeks while Russian troops pummeled the city with artillery. It is now a virtual wasteland, with nearly every building damaged or destroyed, and an unknown number of dead beneath the rubble.

Among the survivors was 6-year-old Ilya Kostushevich, orphaned and alone. Both his parents were killed in the first week of the war.

His mother was struck down by Russian artillery after she left home to find food for her family, Bespalov and Bespalaya were later to learn from police.

Unaware of his wife’s fate, Ilya’s father went looking for her the next day, only to be killed by shelling from Moscow’s army, too, police said.

Little Ilya has told how he was left at a neighbor’s house, where he sheltered in a cold, dark basement with strangers for weeks.

He got so hungry he started to eat his toys, Bespalaya said.

“The men were drinking alcohol and the children of those neighbors bullied him. He was starving and freezing,” Bespalaya told CNN in a hushed voice. She is careful not to bring up Ilya’s traumatizing experience in front of him unprompted, but he has told the woman he now calls “mama” everything about his three terrifying weeks in the basement, she says.

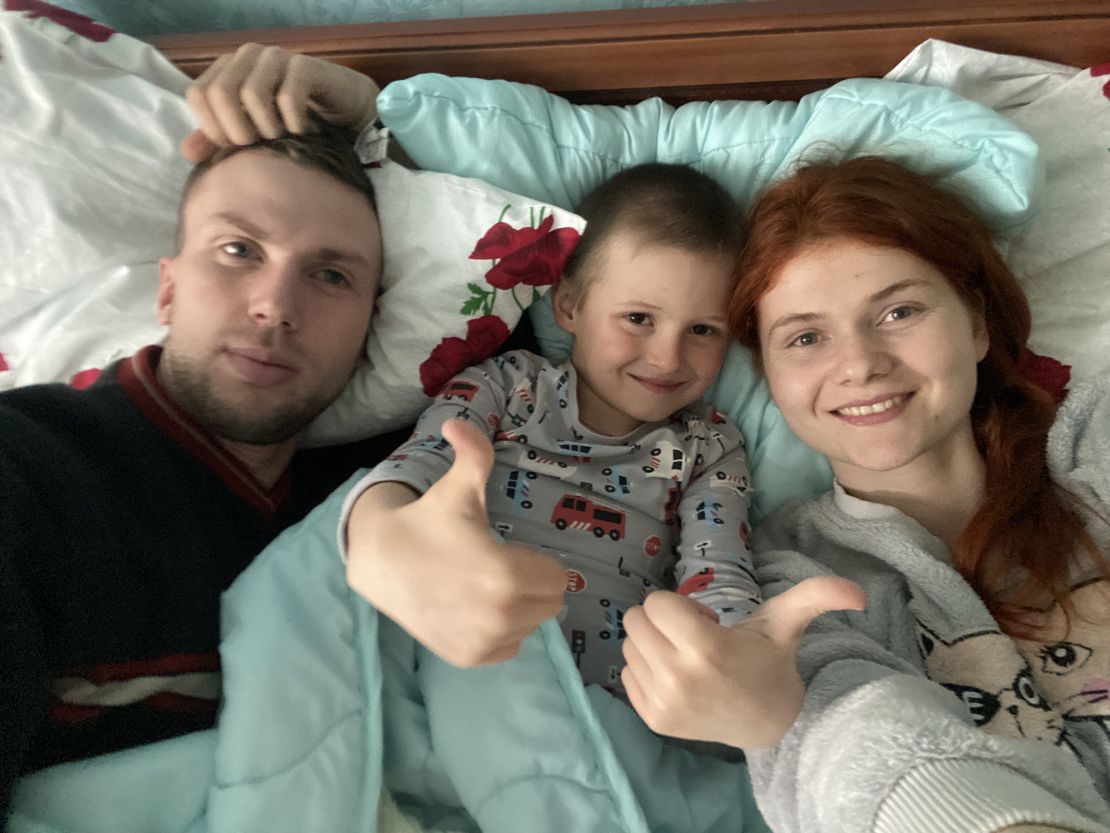

Bespalov and Bespalaya are now Ilya’s legal guardians. They have been a little family for more than six months, and they plan to formally adopt him as soon as possible. All adoption processes are currently suspended in Ukraine due to martial law.

Like any parents, the young couple are fiercely protective of Ilya, sheltering him from the horrors of war the best they can and trying to give him a sense of security and stability.

“You try to take your mind off the fighting and immerse yourself in spending time with your child. We try to create memories of a normal childhood. Work takes time, but we spend every free moment together,” said Bespalov, who as a crucial railroad worker has not been called up for military service.

But there is nothing normal about war. After they posted their appeal on Instagram, the couple set up two spare rooms for the possible arrival of a child – one a nursery with a white crib and blue bedding, the other equipped with a bunk bed and lots of toys.

Bespalaya had worked in an orphanage for several years and felt ready for the challenge of raising a child, no matter the circumstances.

“I just totally stopped being afraid of adoption. I was confident that we would have a child, and I was confident that I could care for anyone and deal with their character,” she told CNN.

But that plan, too, was shattered by war. Soon after it began, the pair were forced to flee their home in Slovyansk, a city in the frontline Donetsk region, for Kyiv.

“Our stability was gone. we both lost our jobs and our home. We lost all our savings, we lost absolutely everything,” Bespalaya said.

“But we gained so much more.”

In April, they finally received the call they had been hoping for, from a volunteer in Mariupol: there was a little boy with no parents, could the couple care for him?

The following morning, they started out on the two-day car journey to Dnipro, where Ilya was sheltering, to meet the boy who would become part of their family.

Once back in Kyiv, they underwent a complex, four-month process to become Ilya’s legal guardians which involved speaking to therapists, many doctor visits, police background checks, and a government search to ensure the boy had no other living relatives. Various donors, including the Shakhtar Donetsk Football Club, helped provide financial support that allowed the family to find a comfortable home.

“Now we have that love, that love that makes you a family. We did not have this baby, but our love is real,” Bespalaya said, with Ilya cuddled between her and Bespalov on a playground bench in Kyiv.

Despite their happiness as a new family unit, life is tougher for Ilya in the evenings, when the capital experiences rolling blackouts caused by Russia’s sustained attacks on the power grid – leaving the family without electricity for hours at a time.

“Sometimes he gets scared,” Bespalaya said. “He is hysterical, and he’ll tell me it’s like being back in Mariupol, in the darkness.”

But little Ilya is learning to cope. As he played with the couple in a living room lit by candles during one of the power outages, he looked up and said: “I am not afraid of the dark anymore. I know the light will turn back on.”