When world leaders at the Group of 20 summit in Bali, Indonesia, issued a joint statement condemning Russia’s war in Ukraine, a familiar sentence stood out from the 1,186-page document.

“Today’s era must not be of war,” it said, echoing what Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi told Russian leader Vladimir Putin during a face-to-face meeting in September.

Media and officials in the country of 1.3 billion were quick to claim the inclusion as a sign that the world’s largest democracy had played a vital role in bridging differences between an increasingly isolated Russia, and the United States and its allies.

“How India united G20 on PM Modi’s idea of peace,” ran a headline in the Times of India, the country’s largest English-language paper. “The Prime Minister’s message that this is not the era of war… resonated very deeply across all the delegations and helped bridge the gap across different parties,” India’s Foreign Secretary Vinay Kwatra told reporters Wednesday.

The declaration came as Indonesian President Joko Widodo handed over the G20 presidency to Modi, who will host the next leaders’ summit in the Indian capital New Delhi in September 2023 – about six months before he is expected to head to the polls in a general election and contest the country’s top seat for a third time.

As New Delhi deftly balances its ties to Russia and the West, Modi, analysts say, is emerging as a leader who has been courted by all sides, winning him support at home, while cementing India as an international power broker.

“The domestic narrative is that the G20 summit is being used as a big banner in Modi’s election campaign to show he’s a great global statesmen,” said Sushant Singh, a senior fellow at New Delhi-based think tank Center for Policy Research. “And the current Indian leadership now sees themselves as a powerful country seated at the high table.”

India bridges ‘multiple antagonists’

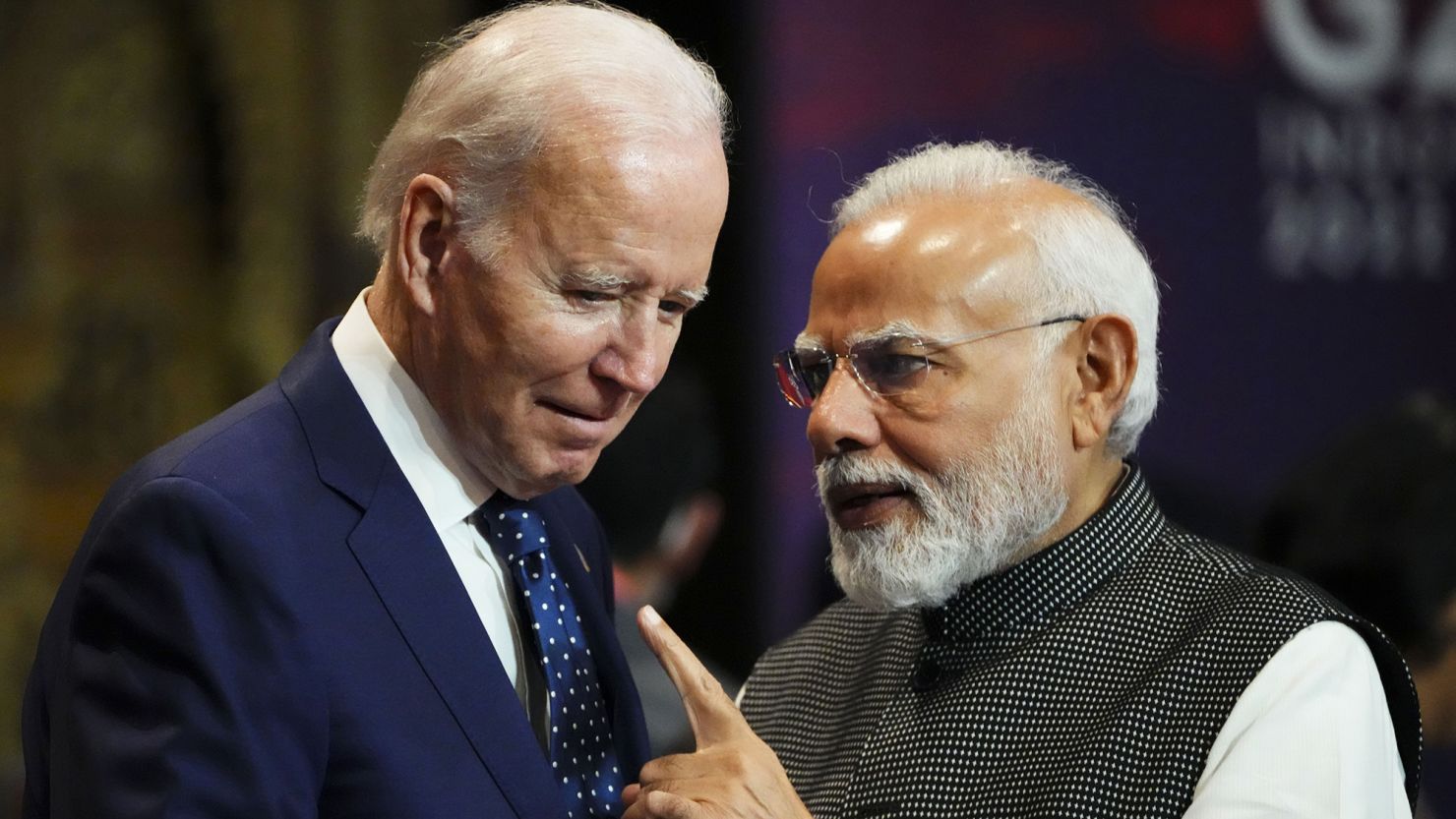

On some accounts, India’s presence at the G20 was overshadowed by the much anticipated meeting between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden, and the scramble to investigate the killing of two Polish citizens after what Warsaw said was a “Russian-made missile” landed in a village near the NATO-member’s border with Ukraine.

Global headlines covered in detail how Biden and Xi met for three hours on Monday, in an attempt to prevent their rivalry from spilling into open conflict. And on Wednesday, leaders from the G7 and NATO convened an emergency meeting in Bali to discuss the explosion in Poland.

Modi, on the other hand, held a series of discussions with several world leaders, including newly appointed British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, ranging from food security and environment, to health and economic revival – steering largely clear of condemning Putin’s aggression outright, while continuing to distance his country from Russia.

While India had a “modest agenda” for the G20 revolving around the issues of energy, climate, and economic turmoil as a result of the war, Western leaders “are listening to India as a major stakeholder in the region, because India is a country that is close to both the West and Russia,” said Happymon Jacob, associate professor of diplomacy and disarmament at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi.

New Delhi has strong ties with Moscow dating back to the Cold War, and India remains heavily reliant on the Kremlin for military equipment – a vital link given India’s ongoing tensions at its shared Himalayan border with an increasingly assertive China.

At the same time, New Delhi has been growing closer to the West as leaders attempt to counter the rise of Beijing, placing India in a strategically comfortable position.

“One of the ways in which India had an impact at the G20 is that it seems to be one of the few countries that can engage all sides,” said Harsh V. Pant, professor in international relations at King’s College London. “It’s a role that India has been able to bridge between multiple antagonists.”

‘Voice of the developing world’

Since the start of the war, India has repeatedly called for a cessation of violence in Ukraine, falling short of condemning Russia’s invasion outright.

But as Putin’s aggression has intensified, killing thousands of people and throwing the global economy into chaos, analysts say India’s limits are being put to the test.

Observers point out Modi’s stronger language to Putin in recent months was made in the context of rising food, fuel and fertilizer prices, and the hardships that was creating for other countries. And while this year’s G20 was looked at through the lens of the war, India could bring its own agenda to the table next year.

“India’s taking over the presidency comes at a time when the world is placing a lot of focus on renewable energy, rising prices and inflation,” Jacob from JNU said. “And there is a feeling that India is seen as a key country that can provide for the needs of the region in South Asia and beyond.”

Soaring global prices across a number of energy sources as a result of the war are hammering consumers, who are already grappling with rising food costs and inflation.

Speaking at the end of the G20 summit on Wednesday, Modi said India was taking charge at a time when the world was “grappling with geopolitical tensions, economic slowdown, rising food and energy prices, and the long-term ill-effects of the pandemic.”

“I want to assure that India’s G20 presidency will be inclusive, ambitious, decisive, and action-oriented,” he said in his speech.

India’s positioning of next year’s summit is “very much of being the voice of the developing world and the global South,” Pant, from King’s College London, said.

“Modi’s idea is to project India as a country that can respond to today’s challenges by echoing the concerns that some of the poorest countries have about the contemporary global order.”

All eyes on Modi

As India prepares to assume the G20 presidency, all eyes are on Modi as he also begins his campaign for India’s 2024 national election.

Domestically, his Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) populist politics have polarized the nation.

While Modi remains immensely popular in a country where about 80% of the population is Hindu, his government has been repeatedly criticized for a clampdown on free speech and discriminatory policies toward minority groups.

Amid those criticisms, Modi’s political allies have been keen to push his international credentials, portraying him as a key player in the global order.

“(The BJP) is taking Modi’s G20 meetings as a political message that he is bolstering India’s image abroad and forging strong partnerships,” said Singh, from the Center for Policy Research.

This week, India and Britain announced they are going ahead with a much anticipated “UK-India Young Professionals Scheme,” which will allow 3,000 degree-educated Indian nationals between 18 and 30 years old to live and work in the United Kingdom for up to two years.

At the same time, Modi’s Twitter showed a flurry of smiling photographs and video of the leader with his Western counterparts.

“His domestic image remains strong,” Singh said, adding it remains to be seen whether Modi can keep up his careful balancing act as the war progresses.

“But I think his international standing comes from his domestic standing. And if that remains strong, then the international audience is bound to respect him.”