The experimental drug lecanemab shows “potential” as an Alzheimer’s disease treatment, according to new Phase 3 trial results, but the findings raise some safety concerns because of its association with certain serious adverse events.

Lecanemab has become one of the first experimental dementia drugs to appear to slow the progression of cognitive decline.

The long-awaited trial data, published Tuesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, comes about two months after drugmakers Biogen and Eisai announced that lecanemab had been found to reduce cognitive and functional decline by 27% in their Phase 3 trial.

A Phase 2 trial did not show a significant difference between lecanemab and a placebo in Alzheimer’s disease patients in 12 months – but the Phase 3 trial data suggests that at 18 months, lecanameb was associated with more clearance of amyloid and less cognitive decline.

“In persons with early Alzheimer’s disease, lecanemab reduced brain amyloid levels and was associated with less decline on clinical measures of cognition and function than placebo at 18 months but was associated with adverse events,” the researchers wrote. “Longer trials are warranted to determine the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

The Alzheimer’s Association said in a statement Tuesday that it welcomes and is further encouraged by the full Phase 3 data.

“These peer-reviewed, published results show lecanemab will provide patients more time to participate in daily life and live independently. It could mean many months more of recognizing their spouse, children and grandchildren. Treatments that deliver tangible benefits to those living with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer’s and early Alzheimer’s dementia are as valuable as treatments that extend the lives of those with other terminal diseases,” it says.

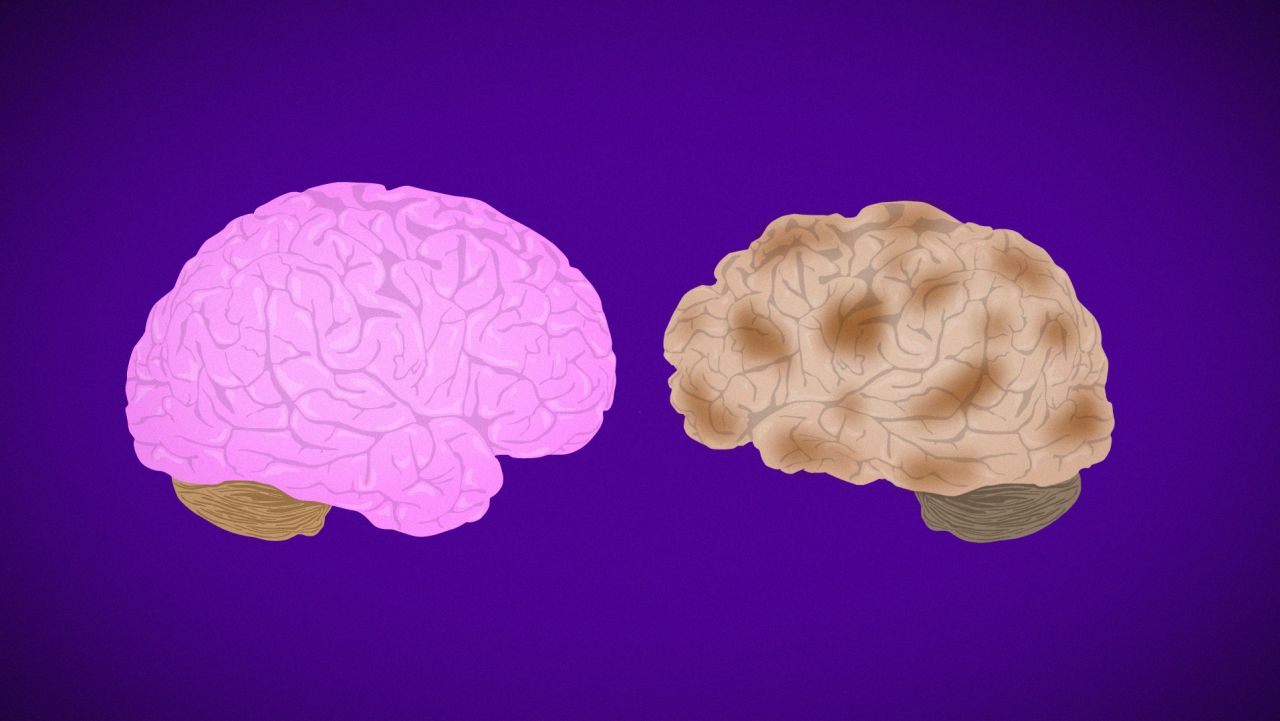

Clearing the amyloid

The Phase 3 trial was conducted at 235 sites in North America, Europe and Asia from March 2019 through March 2021. It involved 1,795 adults, ages 50 to 90, with mild cognitive impairment due to early Alzheimer’s disease or mild Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia.

About half of the participants were randomly assigned to receive lecanemab, given intravenously every two weeks, and the others received a placebo.

The researchers found that participants in both groups had a “clinical dementia rating” or CDR-SB score of about 3.2 at the start of the trial. Such a score is consistent with early Alzheimer’s disease, with a higher number associated with more cognitive impairment. By 18 months, the CDR-SB score went up 1.21 points in the lecanemab group, compared with 1.66 in the placebo group.

“Significant differences emerge as early as the six-month timepoint,” Dr. Christopher van Dyck, an author of the study and director of the Yale Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, said Tuesday during a presentation at the Clinical Trials On Alzheimer’s Disease Conference in San Francisco.

“The lecanemab treatment met the primary and secondary endpoints,” he said.

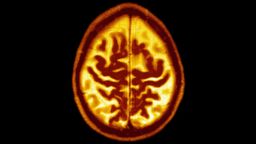

Lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody, works by binding to amyloid beta, a hallmark of the degenerative brain disorder. At the start of the study, the participants’ average amyloid level was 77.92 centiloids in the lecanemab group and 75.03 centiloids in the placebo group.

By 18 months, the average amyloid level dropped 55.48 centiloids in the lecanemab group and went up 3.64 centiloids in the placebo group, the researchers found.

Based on these results, “lecanemab has the potential to make a clinically meaningful difference for people living with the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and their families by slowing cognitive and functional decline,” Dr. Lynn Kramer, chief clinical officer of Alzheimer’s disease and brain health at Eisai, said in a news release.

Evaluating the safety

About 6.9% of the trial participants in the lecanemab group discontinued the trial due to adverse events, compared with 2.9% of those in the placebo group. Overall, there were serious adverse events in 14% of the lecanemab group and 11.3% of the placebo group.

The most common adverse events in the drug group were reactions to the intravenous infusions and abnormalities on their MRIs, such as brain swelling and brain bleeding called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA.

“Lecanemab was generally well-tolerated. Most adverse events were infusion-related reactions, ARIA-H and ARIA-E and headache,” Dr. Marwan Sabbagh, an author of the study and professor at the Barrow Neurological Institute, said during Tuesday’s conference. He added that such events resolved within months.

ARIA brain bleeding was seen among 17.3% of those who received lecanemab and 9% of those in the placebo group; ARIA brain swelling was documented in 12.6% with lecanemab and 1.7% with placebo, according to the trial data.

Some people who get ARIA may not have symptoms, but it can occasionally lead to hospitalization or lasting impairment. And the frequency of ARIA appeared to be higher in people who had a gene called APOE4, which can increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.ARIA “were numerically less common” among APOE4 noncarriers, the researchers wrote.

The researchers also wrote that about 0.7% of participants in the lecanemab group and 0.8% of those in the placebo group died, corresponding to six deaths documented in the lecanemab group and seven in the placebo group. “No deaths were considered by the investigators to be related to lecanemab or occurred with ARIA,” they wrote.

The company aims to file for approval of the drug in the United States by the end of March, according to its news release. The US Food and Drug Administration has granted lecanemab “priority review.”

In July, the FDA accepted Eisai’s Biologics License Application for lecanemab under the accelerated approval pathway, according to the company. The program allows for earlier approval of drugs that treat serious conditions and “fill an unmet medical need” while the drugs are being studied in larger and longer trials.

If the trials confirm that the drug provides a clinical benefit, the FDA grants traditional approval. But if the confirmatory trial does not show benefit, the FDA has regulatory procedures that could lead to taking the drug off the market.

“The FDA is expected to decide whether to grant accelerated approval to lecanemab by January 6, 2023,” the Alzheimer’s Association statement says. “Should the FDA do so, the current [Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services] policy will prevent thousands and thousands of Medicare beneficiaries with a terminal, progressive disease from accessing this treatment within the limited span of time they will have to access it. If a patient decides with their health care provider that a treatment is right for them, Medicare must stand behind them as it does for beneficiaries with every other disease.”

‘This is just the first chapter’

“If and when this drug is approved by the FDA, it will take clinicians some time to be able to parse out how this drug may or may not be effective in their own individual patients,” especially since carriers of the APOE4 gene could be at higher risk of side effects, said Dr. Richard Isaacson, adjunct associate professor of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine, who is not involved in studying lecanemab or its development.

“While this study is certainly encouraging, how this translates to clinical practice, real-world clinical practice, remains to be seen,” he said of the Phase 3 trial data.

Overall, “physicians are starving for any possible therapy out there that can help our patients. I have four family members with Alzheimer’s disease. If I have a family member that comes to me and says, ‘Should I be on this drug?’ In the right patient, at the right dose, for the right duration, with adequate and careful monitoring for side effects, yes, I would suggest that this drug is a viable option,” Isaacson said. “I would say even an important option.”

He added that the experimental drug serves as an example of the important need for personalized medicine in the United States, especially when it comes to Alzheimer’s disease, such as using genetic testing in clinical practice to identify the APOE gene to better individualize the approach to a patient’s care.

“This is just the first chapter in what I hope to become a really long book in disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer’s disease,” he said.

More than 300 Alzheimer’s treatments are in clinical trials, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Alzheimer’s disease was first documented in 1906, when Dr. Alois Alzheimer discovered changes in the brain tissue of a woman who had memory loss, language problems and unpredictable behaviors. The debilitating disease now affects more than 6 million adults in the United States.

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but there are several prescription drugs available to help manage symptoms. Last year, the FDA approved Aduhelm for early phases of Alzheimer’s disease. Before that, the FDA had not approved a novel therapy for the condition since 2003.

Although lecanemab is being tested as an Alzheimer’s drug, it is not a cure, said Tara Spires-Jones, deputy director of the Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the trial.

“Both groups in the trial had worsening symptoms, but people taking the drug did not decline as much in their cognitive skills,” Spires-Jones said in a written statement distributed by the UK-based Science Media Centre. “Longer trials will be needed to be sure that the benefits of this treatment outweigh the risks.”

In general, Alzheimer’s continues to be a “complex” disease, Bart De Strooper, director of the UK Dementia Research Institute, said in a statement distributed by the Science Media Centre.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“We still have a lot to learn about the underlying causes. It is therefore imperative that we continue to invest in discovery research, and through doing so, we may also identify new targets for which we can develop therapies we could use in combination with anti-amyloid drugs like lecanemab,” said De Strooper, who is a consultant for a series of pharmaceutical companies, including Eisai, but has not consulted on lecanemab.

“This trial proves that Alzheimer’s disease can be treated,” he said. “I hope we will start to see a reversal in the chronic underfunding of dementia research. I look forward to a future where we treat this and other neurodegenerative diseases with a battery of medications adapted to the individual needs of our patients.”