When Chief Justice William Rehnquist helped decide the 2000 presidential election, his radical legal theory failed to gain a majority. But today’s conservative court is giving it another chance, in a case that could transform elections in 2024 and beyond.

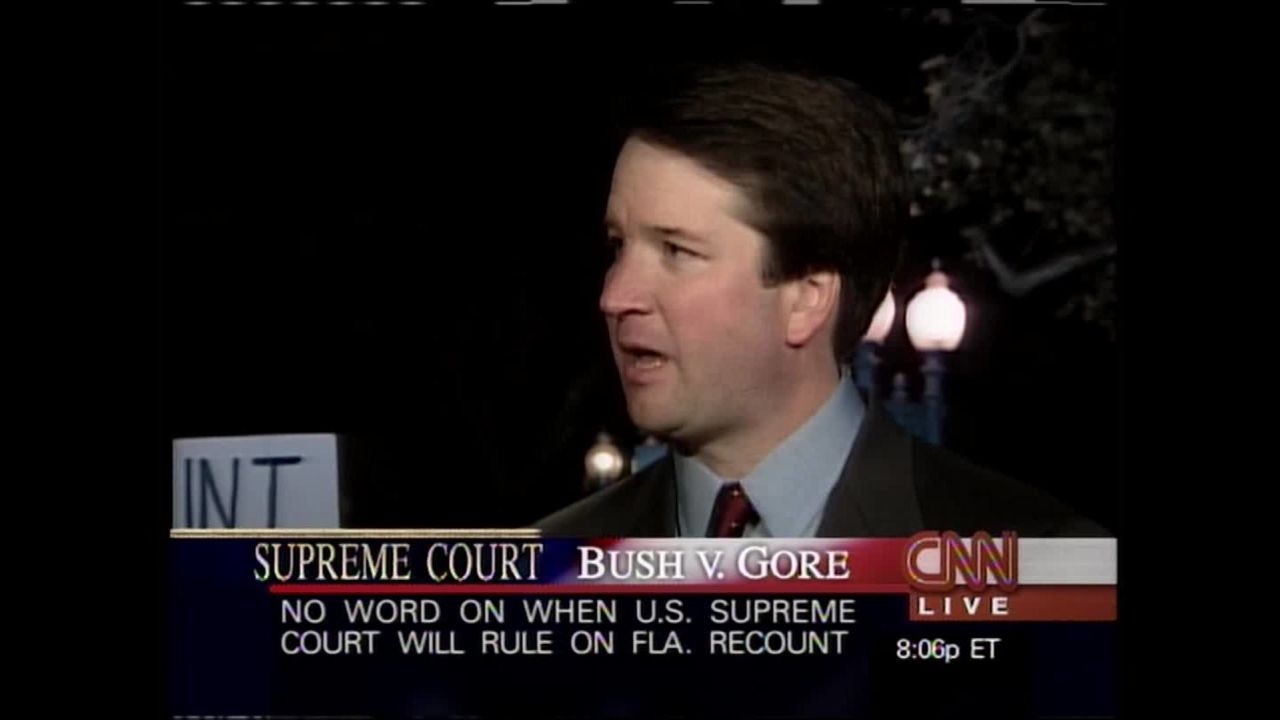

Back in 2000, the justices by a 5-4 vote stopped Florida recounts and ensured that the state’s decisive Electoral College votes went to then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush over then-Vice President Al Gore.

A new dispute to be heard Wednesday, coming at an even more polarized time in US history, could be equally consequential, determining the ground rules for elections nationwide and, eventually, influencing who becomes president.

Rehnquist’s approach, which has become known as the independent state legislature theory, would give complete power to state legislatures to control election practices, at the expense of state courts ensuring constitutional protections.

If the court adopts his approach in a North Carolina dispute over the Constitution’s Elections Clause, the consequences could be staggering. It would prevent judges from throwing out unfair redistricting maps or invalidating measures that restrict access to the polls. If extended to the terms of the Electors Clause, state legislators could completely shape the appointment of a state’s presidential elections, even if contrary to the popular vote.

Wednesday’s case traces back to an extreme partisan gerrymander drawn by the Republican-controlled North Carolina legislature. The state supreme court struck down the map as a violation of the North Carolina constitution’s guarantees of free elections, equal protection, and free speech and assembly.

In their appeal to the justices, North Carolina legislators argue that legislatures have complete authority within the state on elections, free of any check by state judges based on state constitutional guarantees. The North Carolina state officials defending the state court, joined by Common Cause and outside public interest groups, said that view misinterprets the US Constitution and, if adopted, would reverse more than a century of Supreme Court precedent.

During the Bush v. Gore oral arguments in December 2000, Justice Anthony Kennedy warned of the dangers to democracy if state constitutions were bypassed in elections controversies.

“It seems to me essential to the republican theory of government that the constitutions of the United States and the states are the basic charter,” said Kennedy, a centrist conservative, “and to say that the legislature of the state is unmoored from its own constitution, and it can’t use its courts … it seems to me a holding which has grave implications for our republican theory of government.”

When Rehnquist wrote his separate opinion in the case, he acknowledged that the justices usually defer to state courts on issues of state law. “But there are a few exceptional cases in which the Constitution imposes a duty or confers a power on a particular branch of a State’s government. This is one of them,” he wrote in a concurring opinion, joined by Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas.

That idea laid dormant for two decades but was revived by legal allies of former President Donald Trump during the 2020 election, including as he was trying to overturn his defeat. And since then, four of the justices in today’s right-wing supermajority on the Supreme Court have expressed interest in the so-called independent state legislature theory.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh was among the first on the current bench to invoke Rehnquist.

“Under the US Constitution, the state courts do not have a blank check to rewrite state election laws for federal elections,” he wrote in an October 2020 election controversy over Wisconsin state rules. “As Chief Justice Rehnquist persuasively explained in Bush v. Gore … the text of the Constitution requires federal courts to ensure that state courts do not rewrite state election laws.”

How Bush v. Gore was decided

When the Supreme Court cut off the Florida recounts in 2000, the main five-justice opinion said the standards that counties were using varied too widely to be fair.

They referred to the difficulty of recounting some of Florida’s punchcard ballots. Among the memorable images from the 36-day legal ordeal that culminated in the Bush v. Gore decision are those of Florida officials examining ballot chads, some “hanging,” some “dimpled,” to try to discern voters’ intentions.

The Florida Supreme Court had ordered the various county recounts, as the Florida secretary of state went ahead and certified a 537-vote margin for Bush, out of six million votes cast. When the justices forced an end to the recounts, the majority cited equal protection and due process guarantees, as well as an imminent deadline.

The justices emphasized that the deadline that year for the selection of state electors was December 12 – the date on which they were ruling, after expedited arguments the previous day. “(T)here is no recount procedure in place that comports with minimal constitutional standards,” they wrote, finding that the state was essentially out of time.

The majority also characterized its decision as a Florida one-off, writing, “Our consideration is limited to the present circumstances, for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities.”

The Bush v. Gore opinion was unsigned but anchored in the views of Kennedy and fellow centrist conservative Sandra Day O’Connor. Joining them were Rehnquist, Scalia and Thomas.

Then those three justices went further in a concurring opinion and said they believed additional grounds justified reversing the Florida Supreme Court’s decision.

“In most cases, comity and respect for federalism compel us to defer to the decisions of state courts on issues of state law. That practice reflects our understanding that the decisions of state courts are definitive pronouncements of the will of the States as sovereigns,” Rehnquist explained.

But, he wrote, elections are different. He pointed to the Electors Clause of the Constitution’s Article II, which says, “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,” electors for president and vice president.

(The related Elections Clause in the Constitution’s Article I, at issue in the North Carolina controversy, dictates that “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.”)

Focusing on the word “Legislature,” Rehnquist wrote in 2000 that term and context “leaves it to the legislature exclusively to determine the method” for appointing presidential electors. “This inquiry does not imply a disrespect for state courts but rather a respect for the constitutionally prescribed role of state legislatures,” he added.

No other justices among the nine, with the exception of Scalia and Thomas, accepted that view. It faded with the broader legal reasoning of Bush v. Gore over the years. For two decades, no Supreme Court justice cited any of Bush v. Gore for any proposition, except Thomas passingly in a footnote in a 2013 Arizona election case.

The revival of Bush v. Gore

That changed in 2020 as Republican litigators aligned with former President Donald Trump tried to revive Bush v. Gore in state litigation to challenge ballot practices. They invoked the majority’s view related to standards for counting ballots, as well as the Rehnquist proposition for absolute state legislative authority.

The various dimensions of Bush v. Gore lacked any traction in lower courts during the 2020 cycle, yet, important for the pending case, several of the new conservative justices expressed openness to the Rehnquist theory.

Kavanaugh, who cited Rehnquist in the Wisconsin election dispute, had been on George W. Bush’s legal team in 2000, as had now-Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett. After Bush became president, Kavanaugh joined the administration and then in 2006 was appointed by Bush to an appellate court. Trump elevated him to the Supreme Court in 2018, to replace Kennedy.

In the Wisconsin controversy over a court-ordered deadline extension for absentee ballots, Kavanaugh also joined a separate opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch, whom Trump had chosen to succeed Scalia in 2017.

Touting state legislative authority, without citing Rehnquist, Gorsuch wrote, “The Constitution provides that the state legislatures – not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials – bear primary responsibility for setting election rules.”

Since then, as the Supreme Court took preliminary action on the North Carolina case, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, along with Alito and Thomas (the only justice from 2000 still serving) have made plain their interest in the state legislators’ arguments.

“There is no doubt that this question is of great national importance,” Alito wrote earlier this year, as he encouraged his colleagues to take up the North Carolina case.

Defining the ‘legislature,’ and ‘what chumps’ indeed

Both sides in the controversy of the North Carolina partisan gerrymander delve deep into the structure of the Constitution and its history. Both insist their respective interpretation of the word “Legislature” should prevail.

Legal scholars, however, overwhelmingly endorse the view that binds state legislatures to their state constitutions.

North Carolina solicitor general Ryan Park and lawyers for the outside groups directly challenging the state legislators argue that the justices would be reversing the historical understanding if they rule that legislatures are free of their own state constitutional limits.

“It is rare to encounter a constitutional theory so antithetical to the Constitution’s text and structure, so inconsistent with the Constitution’s original meaning, so disdainful of this Court’s precedent, and so potentially damaging for American democracy,” lawyers for Common Cause and the other non-state parties said in their brief.

North Carolina legislators, for their part, argue that the Constitution’s framers gave state legislatures a favored role in elections, to be overridden only by Congress. “The Elections Clause’s allocation of authority to state legislatures,” they contend, “would be emptied of meaning if state courts could seize on vaguely worded state-constitutional clauses to replace the legislature’s chosen election regulations with their own.”

As both sides look to the Constitution’s history and the few past cases, such as Bush v. Gore, that explored the meaning of “Legislature,” they have also touched on a lesser known, but relevant, 2015 dispute over an independent redistricting commission in Arizona. There the Supreme Court majority, over a caustic dissent by Roberts, reviewed a version of the Rehnquist interpretation of legislative authority.

That 5-4 case arose after the GOP-led legislature in Arizona sought to invalidate the redistricting commission based on arguments that it unconstitutionally usurped state legislative control of voting districts. That case came down to the word “Legislature” in the Elections Clause.

Again, Kennedy had definite views of the constitutional checks and balances. He joined with the four liberals at the time to uphold the independent redistricting commission.

The senior justice in the majority at the time, Kennedy, assigned the opinion to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who wrote for the majority that the notion of “legislature” extends beyond the basic institution to its legislative authority and as such covers the ballot initiative through which Arizona voters created the independent commission.

Ginsburg cited the history and purpose of the Elections Clause, as well as “the animating principle of our Constitution that the people themselves are the originating source of all the powers of government.”

Roberts, who once was a law clerk to Rehnquist and succeeded him in 2005, dissented, along with Scalia, Thomas and Alito. Roberts argued the majority had misread the Constitution’s multiple references to “Legislature,” and he used as evidence the adoption of the 17th Amendment. Ratified in 1913, the amendment ended the practice of state legislators choosing US senators, allowing voters in the states, “the people thereof,” to choose them directly.

As Roberts derided the majority’s interpretation of the “Legislature” phrase, he observed that, “The Amendment resulted from an arduous, decades long campaign in which reformers across the country worked hard to garner approval from Congress and three-quarters of the states.

“What chumps,” the chief justice declared. “Didn’t they realize that all they had to do was interpret the constitutional term ‘the Legislature’ to mean ‘the people’?”