As he began writing an angry dissent in a gay rights case 23 years ago, Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens was comparing the majority’s decision against a gay man to Nazi persecution.

“What is this but a constitutionally prescribed pink triangle?” Stevens wrote in a private first draft of his opinion, referring to the triangles affixed to the clothing of gay prisoners during the Holocaust.

But fellow liberal dissenters David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer argued in a series of personal memos that Stevens’ fury could undermine the force of their legal arguments.

Stevens initially objected, but softened some of his rhetoric to win their backing, a story revealed for the first time in the late justice’s personal papers – reviewed by CNN as the documents were opened this month at the Library of Congress.

“(U)nderlying every analytical flaw the majority makes is its habitual way of thinking about homosexuals,” Stevens wrote in a memo addressed to Souter as he defended the use of Nazi imagery, as well as a reference to the Dred Scott opinion that endorsed slavery in 1857. “It is critical for the dissent to unmask that reality.”

More broadly, he added, “It is important for us to recognize what this case represents: the latest in a long line of decisions influenced by historical prejudices and explained as the product of a Court caught in the midst of a sea change in social conventions and attitudes,” Stevens added.

Stevens ended up dropping the Nazi and Dred Scott references from his dissent to the majority’s decision in Boy Scouts of America v. James Dale. The majority ruled that the organization could, based on its freedom of expressive association, exclude a gay scoutmaster because of the Scouts opposition to homosexuality.

As the Supreme Court’s attitude toward gay rights has evolved in recent decades, dissenting justices have often divided in their level of moral outrage and how to express it publicly. Such divisions are likely to continue when the court acts soon in another major case regarding First Amendment rights and LGBTQ interests.

Stevens, a 1975 appointee of Republican President Gerald Ford, is not as identified with a broad reading of individual privacy as was, for example, the late Justice Harry Blackmun, with whom Stevens served in his early years, or with LGBTQ interests, as was Justice Anthony Kennedy, who eventually became the author of major gay rights decisions, including the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges that declared a constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

But Stevens, who retired in 2010 and died in 2019, sought broad constitutional protection for gay people including as he dissented in 1986 when the high court upheld a Georgia sodomy ban. That decision in Bowers v. Hardwick rejected arguments that the Constitution’s guarantee of personal liberty and privacy extends to consensual relations between gay men. That case was eventually reversed, in 2003, by a court majority that leaned, in fact, on the 1986 dissent by Stevens.

The current pending case involving LGBTQ interests and First Amendment rights – 303 Creative v. Elenis – was brought by a website designer who said she has a free speech right to decline to make wedding websites for same-sex couples. During oral arguments, a majority of the justices sounded sympathetic to the web designer’s claim. A decision is expected at the end of the court’s term late next month.

Stevens’ archives also make clear the difficulty of negotiating as late-June deadlines loom. “Our time is so short,” Ginsburg wrote to Stevens in the Boy Scouts case. “I am just setting out everything in my head, without the pruning I might do were we in April rather than in June.”

Were the Boy Scouts discriminating against gay people?

Back in 2000, the Boy Scouts controversy was one of the most contentious of the session. “This case is about the freedom of a voluntary association to choose its own leaders,” the Scouts’ lawyer told the justices during oral arguments. “Boy Scouting is so closely identified with traditional moral values that the phrase, he’s a real Boy Scout, has entered the language.”

The Scouts were appealing a New Jersey state court decision that found that the group had violated a state anti-discrimination law when it revoked James Dale’s position as an assistant scoutmaster after learning he was gay.

The Supreme Court’s 5-4 majority, in an opinion by then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist, reversed the state court, saying New Jersey could not use the statute to force the Scouts to reinstate Dale without violating the group’s First Amendment right of expressive association.

But perhaps with an eye toward looming questions of prejudice against gay people, Rehnquist emphasized, “We are not, as we must not be, guided by our views of whether the Boy Scouts’ teachings with respect to homosexual conduct are right or wrong; public or judicial disapproval of a tenet of an organization’s expression does not justify the State’s effort to compel the organization to accept members where such acceptance would derogate from the organization’s expressive message.”

Rehnquist was joined in the decision by Justices Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas.

The Stevens dissenters disagreed that acceptance of Dale would conflict with the Scouts’ overriding mission and public message. They said the organization had failed to put forth a “clear, unequivocal statement” that homosexuality was incompatible with the organization’s work.

‘Any reference to Hitler or the Nazis is, I think, open to serious possibilities of misinterpretation’

The deepest differences among those on the left emerged as Stevens compared prejudice against gay people to historic racial and religious discrimination.

Over his long legal career, including a total 40 years as a judge, Stevens could not be pigeonholed. He was first appointed to a federal appellate court by Republican President Richard Nixon in 1970, then elevated by Ford in 1975.

An independent streak marked Stevens during his early decades, but by 2000 he was solidly on the left side of a bench that had grown more conservative.

As he was concluding his first draft of the dissent in the Scouts case, circulated to his colleagues on June 14, he referred to the “ancient roots” of unfavorable opinions about gay people.

And he warned that the majority’s view of the First Amendment could allow organizations to exclude such disfavored people, irrespective of whether the organization engages in any expressive activities.

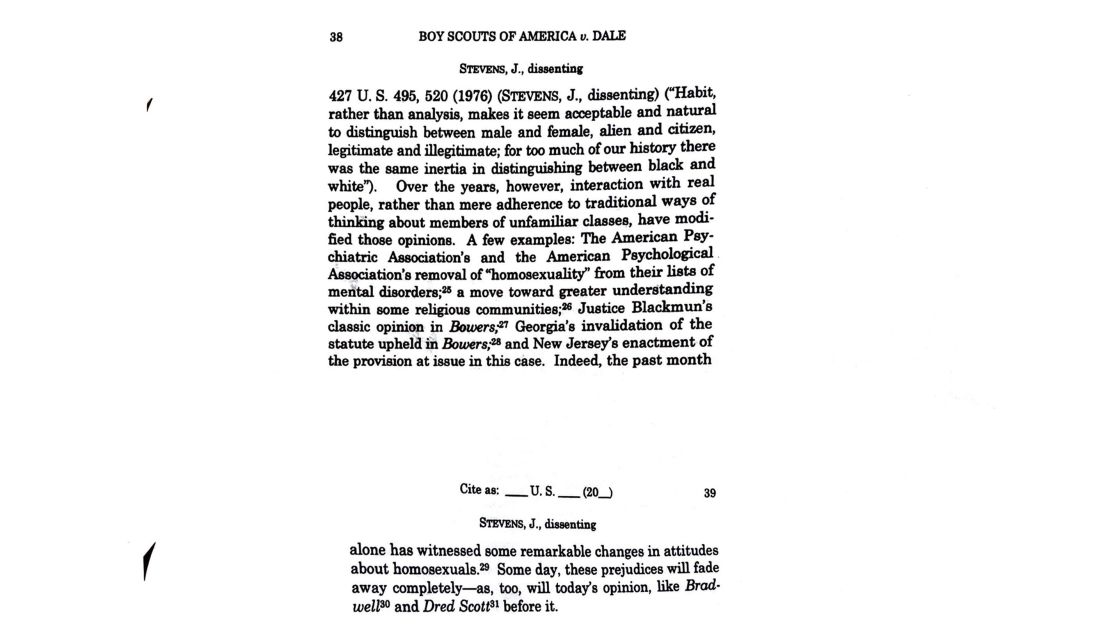

“That cannot be, and never has been the law,” Stevens wrote. “The only possible explanation for the majority’s holding, then, is that homosexuals are simply so different from the rest of society that their presence alone – unlike any other individual’s – should be singled out for special First Amendment treatment. What is this but a constitutionally prescribed pink triangle?”

Stevens was also observing in this final part of his draft that drew the strongest objection from fellow liberals that people’s views were indeed changing.

“Some day, these prejudices will fade away completely – as, too will today’s opinion,” as, he added, was the fate of the 1857 Dred Scott decision.

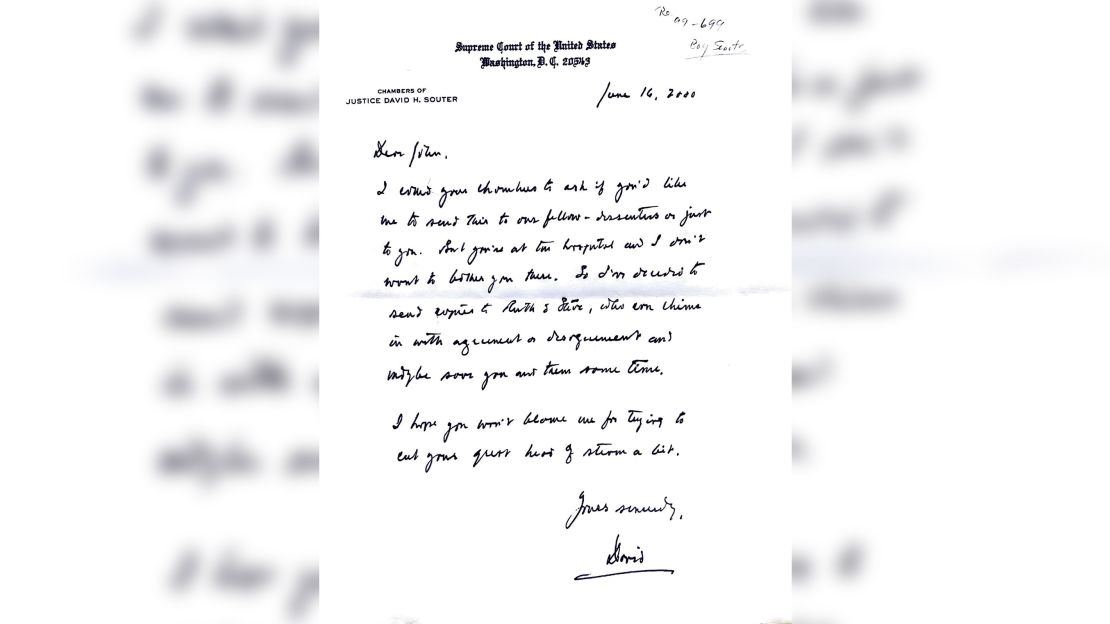

Two days after he received Stevens’ draft, Souter, who like Stevens was appointed by a Republican (George H.W. Bush) but landed on the left, sent him a hand-written note. He wanted to let Stevens know that he would be conveying suggestions for the legal argument Stevens laid out and its tone.

“I hope you won’t blame me for trying to cut your great head of steam a bit.”

Souter’s typed memo to Stevens then detailed 11 points, including a request to significantly pare back a section regarding discrimination against gays and its historic parallels.

“Dred Scott is a bit rough,” Souter said.

Before Stevens could respond to Souter, Ginsburg sent Stevens a note, agreeing with Souter and setting out her own nine points. Of the pink triangle image, she wrote, “It’s inflammatory.”

She also wrote of the final section Stevens had drafted, “I share David’s view that Part VI is preaching to the already converted and likely to distract the uncommitted.” She suggested critics would find the tone excessive.

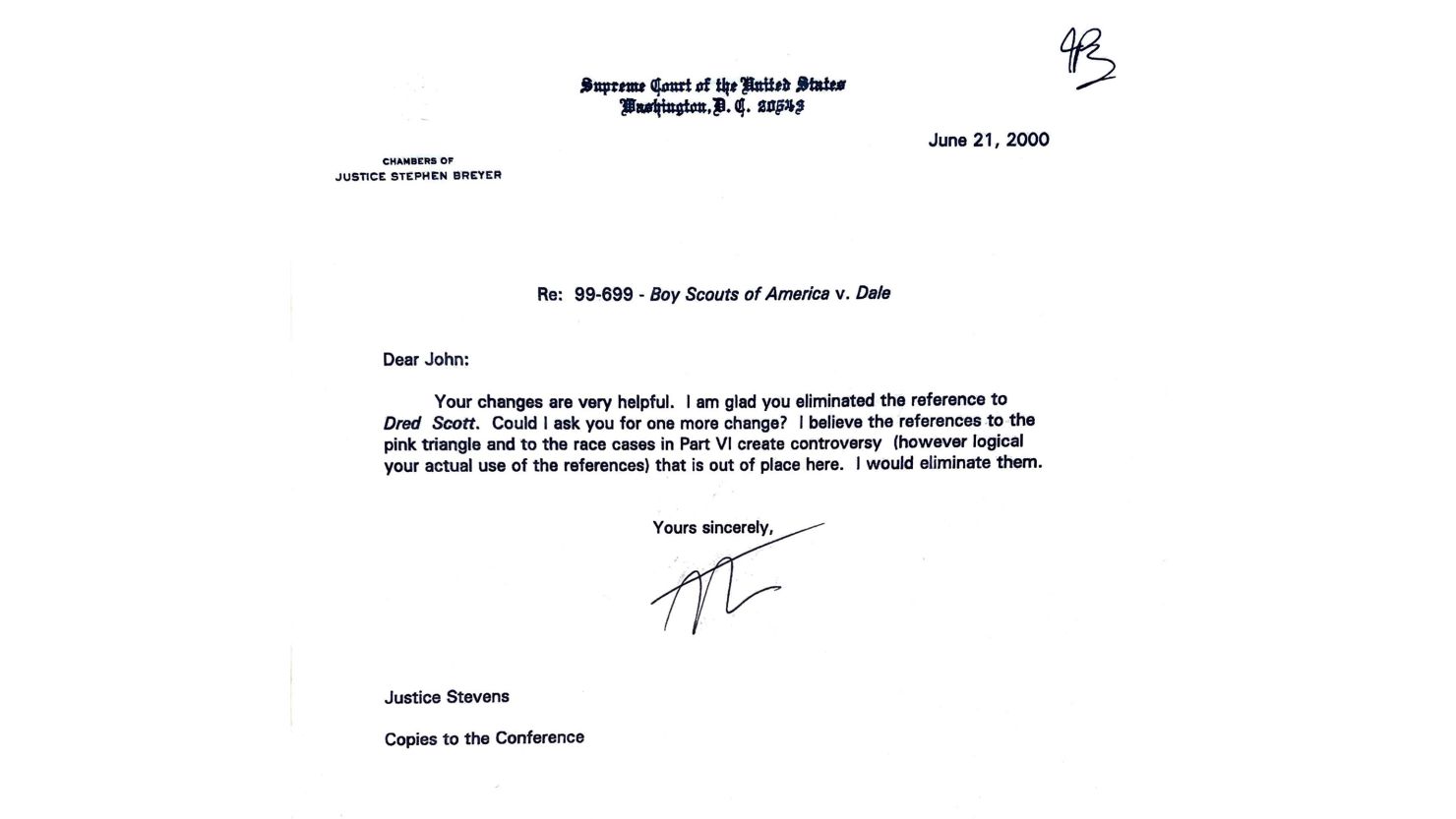

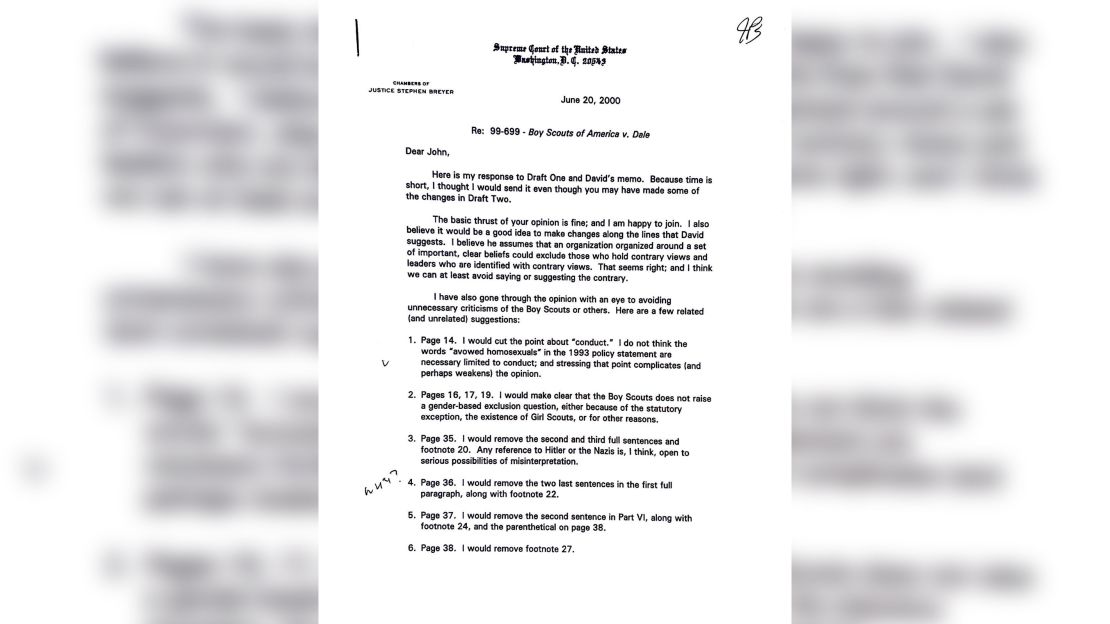

The next day, Breyer sent Stevens his own a seven-point memo. He, too, suggested Stevens delete the pink triangle image. “Any reference to Hitler or the Nazis is, I think, open to serious possibilities of misinterpretation,” Breyer wrote. He and Ginsburg were the only two Jewish justices serving at the time.

Breyer, who had been an Eagle Scout in his youth, added, “I have also gone through the opinion with an eye to avoiding unnecessary criticisms of the Boy Scouts or others.”

Stevens pulls back – eventually

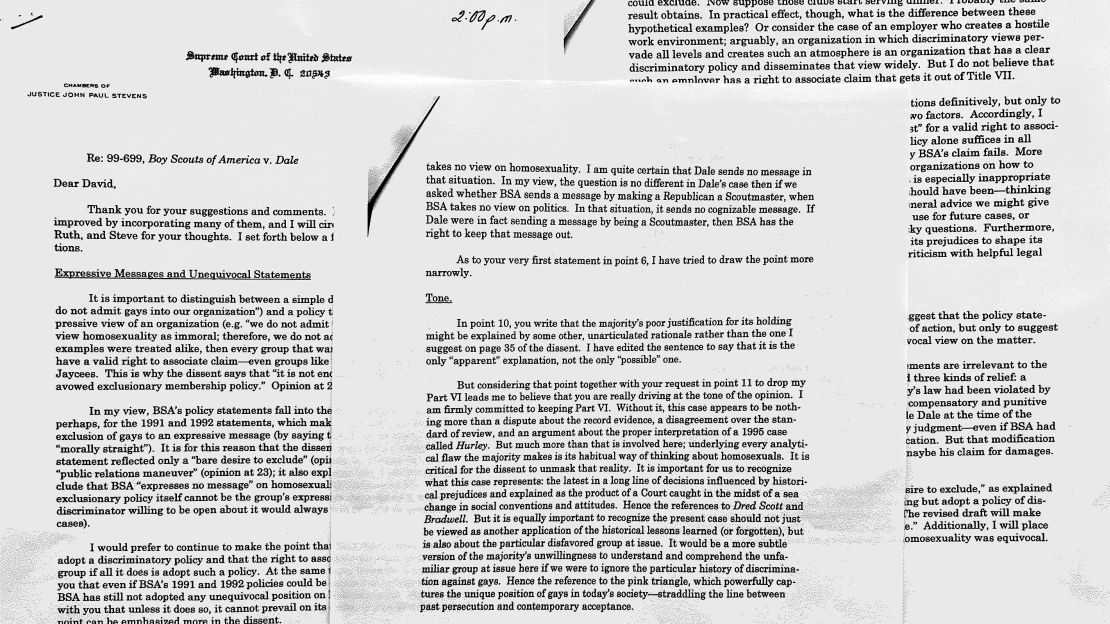

Stevens distributed a revised draft on June 20, telling the three colleagues on the left, “The second revised draft of my dissent has incorporated many of the changes you suggested. I still welcome any additional comments you might have.”

Breyer sent another note the next day, highlighting off-putting phrases that remained: “Your changes are very helpful. I am glad you eliminated the reference to Dred Scott. Could I ask you for one more change? I believe the references to the pink triangle and to the race cases in Part VI create controversy (however logical your actual use of the references) that is out of place here. I would eliminate them.”

Stevens decided to write a separate memo explaining his reasons for resisting many of the requests, including for removal of the Nazi imagery.

“[I]t is … important to recognize the present case should not just be viewed as another application of the historical lessons learned (or forgotten), but is also about the particular disfavored group at issue,” Stevens wrote. “It would be a more subtle version of the majority’s unwillingness to understand and comprehend the unfamiliar group at issue here if we were to ignore the particular history of discrimination against gays. Hence the reference to the pink triangle, which powerfully captures the unique position of gays in today’s society – straddling the line between past persecution and contemporary acceptance.”

Souter was insistent, however, about boosting the legal arguments and bringing down the temperature. He also believed Stevens needed to stress that the case did not involve any possible inappropriate misconduct.

“I think we should make it very clear somewhere at the beginning of the opinion that this is not an issue in the case,” Souter wrote, noting that the Scouts’ “sole defenses to the New Jersey law are speech and expressive association defenses. Would you please mention the express disclaimer of conduct or fear of conduct as a basis for the Scouts’ position?”

Souter implored Stevens – again – to drop the Nazi reference.

“Even with your modification, the reference to the pink triangle is something I could not join,” Souter wrote. “Whereas the first version could have been read to say implicitly that the majority think like Nazis, the present qualification still leaves open the implication that the majority is too na?ve to realize that it is thinking like Nazis.”

Souter continued to challenge Stevens’ final section focused on evolving attitudes toward gay people.

“By placing the focus on the heartening progress of changing attitudes toward gay people, I fear that the discussion not only changes the focus of this case from the First Amendment to gay rights as such, but obscures the point that the First Amendment is there to protect speech that we hate and has necessarily got to protect some expressive associational objectives that we despise,” he wrote.

Ginsburg largely agreed with Souter, urging Stevens to accept Souter’s points: “If you adopt them, I think the opinion will have more power to persuade and will be less susceptible to the charge of partisanship.”

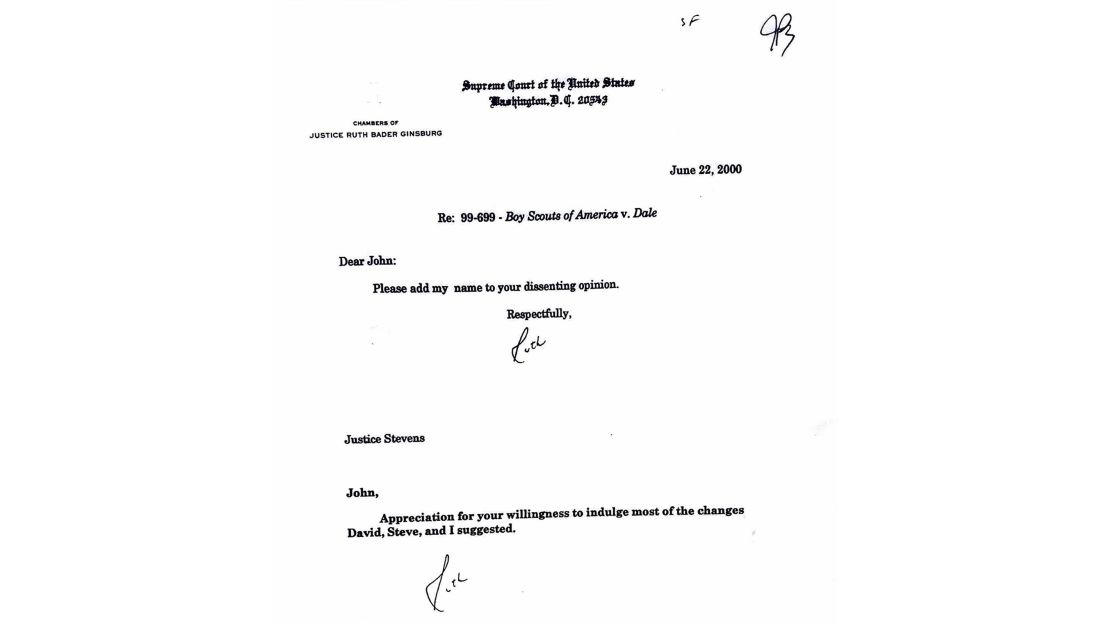

Stevens was not going to cut his concluding section, but he finally agreed to trim the pink triangle reference. That move on June 22 persuaded Ginsburg and Breyer to join his dissent.

In a private note only to Stevens, Ginsburg wrote, “Appreciation for your willingness to indulge most of the changes David, Steve, and I suggested.”

Souter, for his part, decided to sign Stevens’ dissenting opinion but also write a separate statement referring to Stevens’ conclusion about changing attitudes toward gay people. Both were issued, with Rehnquist’s decision, on June 26.

“The fact that we are cognizant of this laudable decline in stereotypical thinking on homosexuality should not, however, be taken to control the resolution of this case,” Souter wrote, later adding, “The right of expressive association does not, of course, turn on the popularity of the views advanced by a group that claims protection. Whether the group appears to this Court to be in the vanguard or rearguard of social thinking is irrelevant to the group’s rights. I conclude that BSA has not made out an expressive association claim, therefore, not because of what BSA may espouse, but because of its failure to make sexual orientation the subject of any unequivocal advocacy, using the channels it customarily employs to state its message.”

Ginsburg and Breyer also signed onto his words.

The power of dissents

Toward the end of his tenure, Stevens routinely found himself in dissent. But he believed in the power of such dissenting statements to affect future majorities.

Three years after the Boy Scouts decision, Kennedy, who was in the majority then, penned a decision overturning the 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick ruling. (O’Connor, who had been in the majority in Bowers and in Boy Scouts, concurred in the bottom-line judgment.)

As Kennedy wrote for a new majority (that included Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg and Breyer), Kennedy looked back to 1986 and asserted that “Justice Stevens’ analysis, in our view, should have been controlling in Bowers and should control here.”

Kennedy quoted Stevens’ dissent as he emphasized in the new 2003 opinion in Lawrence v. Texas that states may not prohibit a particular practice, even if they’ve traditionally viewed it as “immoral,” and that constitutional protections for intimate relations extend to choices made by unmarried as well as married persons.

In Stevens’ 2019 memoir, “The Making of a Justice,” he referred to that Kennedy decision and others that followed.

“Though vindication is always satisfying,” Stevens wrote, “I’ve taken particular satisfaction in seeing the seeds I planted in my Bowers dissent … grow to strike down anti-sodomy statutes in Lawrence, which in turn has led to an ever greater expansion of liberty and equality for our fellow citizens in the later decisions United States v. Windsor, which struck down the Defense of Marriage Act, and Obergefell v. Hodges, which recognized that the fundamental right to marry cannot be denied to same-sex couples.”

“Tony Kennedy was of course instrumental in these groundbreaking decisions, but I like to think that, even though I had left the bench, I had a hand in them as well,” he added.

It is true that justices in dissent often have an eye on the future and a chance to draw the majority – eventually.

“A dissenting opinion is often a lonely perch,” Stevens wrote, “but one of the great benefits of our permitting the dissenting justice to share his or her views with the world is the possibility that in time others will come to agree.”

CNN’s Devan Cole contributed to this report.