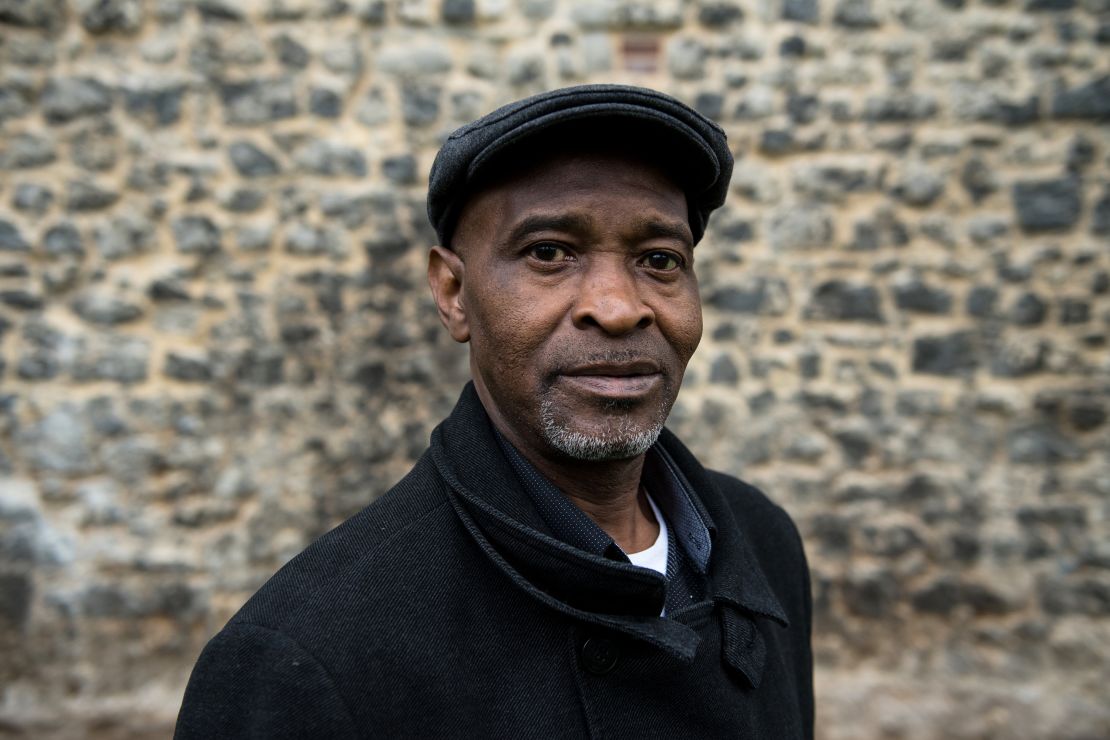

Carl Nwazota was born and grew up in the London suburb of Wembley to parents from Jamaica and Nigeria. For 26 years, he was a UK citizen with a British passport – until it was confiscated by the Home Office after he tried to renew it in 2000, he told CNN.

For the next 22 years, Nwazota lived in constant fear of being deported as his life began to unravel.

His business was closed because he was prevented from working by the Home Office, and he could not gain employment or social housing due to his lack of documents, he said. He was forced to live in temporary accommodation, with intermittent periods of homelessness. He watched the world pass him by from the fringes of society: sleeping in a tent under a shop window, or in an abandoned van in a supermarket car park. Often, he would go to bed hungry due to his benefits being stopped, he recalled – as “no fixed abode” became his new identity in the corridors of the job center.

Christmases and birthdays passed by for almost two decades until the Home Office acknowledged that Nwazota was a British citizen over a phone call in 2018, he said.

For the next four years, Nwazota says, he remained homeless while he struggled to regain his passport. Many of his documents were lost after he claims the council threw away his tent, and he could not receive response letters from the Home Office as he had no permanent address.

“I had been told I was a British citizen – but I was still waiting to get back my passport, waiting for an apology from the Home Office – all while living in a van. I’m not a weak guy but I had no hope. I tried to take my own life,” he said.

Nwazota has since recovered and received his passport from the Home Office in 2022. “The first thing I did when I got my passport back was get a job – and I’m proud to say, I work as a bin man (refuse collector). But even though I’m back in the real world – it’s too late for me. I’m 49 years old now. The Home Office has taken my life from me.”

Nwazota is one of thousands who found their lives derailed in what became to be known as the Windrush scandal, which saw the British Home Office deny residency rights and citizenship to many people who had been living in the UK legally for most, if not all, of their lives.

The victims were members and descendants of the so-called Windrush generation – mostly Caribbean migrants who moved to Britain in the post World War II-era in answer to a call for labor shortages, with the first arriving on the Empire Windrush 75 years ago Thursday. Citizens of former British colonies in South Asia and Africa also became entangled in the scandal.

Like Nwazota, many of their children had been born in Britain and have known no other home, yet also had their UK citizenship revoked.

Experts told CNN this was due to the UK government’s “hostile environment” policy – a government crackdown on immigration that misclassified the Windrush generation as illegal immigrants.

This has led to multiple generations suffering often devastating harm: job losses, home evictions, no access to healthcare, detentions and even deportations, as outlined in the government commissioned Windrush Lessons Learned Review. In 2018, the Windrush Compensation Scheme was set up to provide compensation to victims of the scandal.

In April that year, Britain’s then-Prime Minister, Theresa May, apologized for her government’s treatment of some Caribbean immigrants and insisted they were still welcome in the country.

But on the 75th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush, thousands are still struggling to access compensation despite the Home Office reinstating their British citizenship.

In April, a report by the NGO Human Rights Watch stated that the Windrush compensation scheme “is failing victims and violating the rights of many to an effective remedy for human rights abuses they suffered.”

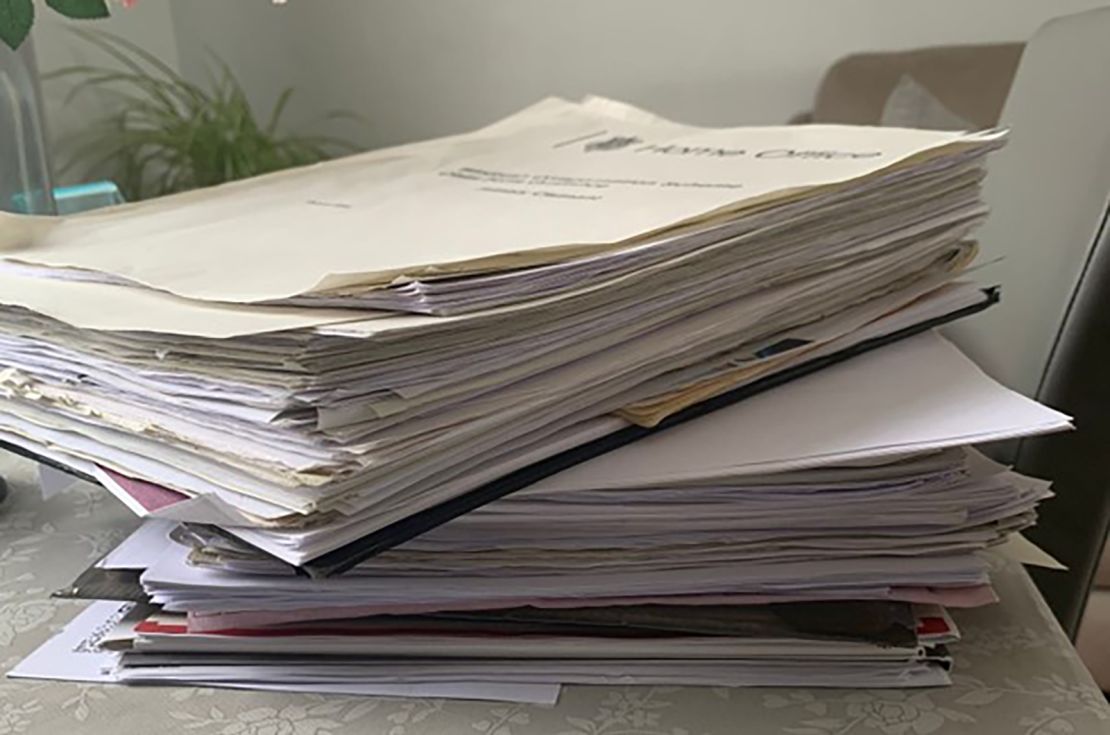

Nwazota has applied to the Windrush Compensation Scheme four times – but his application has always been rejected.

In documents seen by CNN, Nwazota was told by the Home Office that he meets the eligibility criteria to apply for compensation but that it has been unable to determine “whether he suffered detrimental impacts” due to a lack of evidence.

Nwazota is currently struggling to find a lawyer to take his case due to his lack of documents and funds.

Thousands without compensation

According to the latest Home Office statistics, 1,518 people have received compensation so far. Another 381 have had their claims refused or withdrawn due to ineligibility and 1,988 have claims that “meet the eligibility criteria” but have been awarded zero compensation. This suggests that of an estimated 15,000 victims believed to be eligible for compensation, some 90% have yet to receive any payout since the scandal broke five years ago.

Anna Steiner, a lawyer and academic who represents Windrush claimants, told CNN that the Windrush compensation scheme is “not fit for purpose.”

“The government has access to all the victims’ documents: health records, information from the passport office and their employment history. These are British people who have paid tax and national insurance, have worked for all their lives and the government has confirmed their status as UK citizens, and yet, victims are still being denied access to compensation for the harm caused to their lives,” Steiner said.

“Even when you’ve spent months gathering evidence, drafted clear statements, and have demonstrated a clear impact on (victims’) lives, applications are not assessed properly by the Home Office. There seems to be a bureaucratic tick-box attitude to the claims where people are not recognized as human beings,” Steiner added.

Thomas Tobierre was stripped of the right to work after being told he was not a British citizen and has subsequently received compensation, but his wife Caroline, who was also entitled to compensation under the Windrush scheme, only received her payment after she died with cancer.

“My wife had to work while she was ill – because I was not allowed to work because of the Home Office,” Tobierre told CNN.

“The level of evidence you have to produce is ridiculous – it is almost impossible to prove your status,” said Charlotte Tobierre, Thomas’ daughter. “Because they took so long to compensate, we ran out of time to enjoy life with my mum. The last year of my mum’s life was ruined – the Windrush scandal overshadowed my mum’s battle with cancer.

“When the compensation arrived, it just about covered the cost of her funeral.”

To make matters more complicated, the Windrush Compensation Scheme does not make allowances for legal costs in making claims, Steiner told CNN.

This means that many of the applicants who have been out of work and accumulated debt cannot afford the legal representation they need to help with their claims, Zita Holbourne, co-founder and national chair of anti-racism group Black Activists Rising Against Cuts and a Windrush campaigner, told CNN.

“Approaching its 75th anniversary, the government should be doing something to make the scheme accessible – and the scheme should take it out of the hands of the Home Office. People have no trust when applying because they are the same institution that detained, criminalized and deported the applicants in the first place,” Holbourne added.

Anthony Bryan, now 65, was 8 years old when he moved to Britain from Jamaica. He told CNN he was detained by the UK government on two separate occasions in 2017 – and was going to be deported to Jamaica by the Home Office until a last-minute intervention from his lawyers. He had also lost his job after he was asked for a right to work permit, he said, and he had been stripped of healthcare access after falling ill. Bryan could not claim benefits, as he did not have the required documents, he added.

His British nationality has since been reinstated. The Home Office has offered him – after deductions – £65,000 and he is appealing. His wife Janet, who is also entitled to compensation, is also appealing her offer under the scheme. Windrush Lives, an advocacy group and victim support network which is helping Janet, says the Home Office is currently disputing the £300 she is claiming for expenses after she repeatedly traveled to visit Bryan while he was wrongfully detained for five weeks.

The Home Office has not yet responded to CNN’s request for comment on these cases and its wider handling of the Windrush Compensation Scheme.

A hostile environment

According to the latest government statistics from the Home Office, 1,227 claimants are seeking a review. Meanwhile, the number of people being awarded zero compensation is continuing to rise – particularly over the past year. While in April 2022 there were only 26 applicants eligible but receiving zero compensation, a year later this number had risen almost six-fold to 152.

As the backlogs and rejections grow, Home Secretary Suella Braverman issued a statement in January that rowed back on three of the recommendations from the government-commissioned “Windrush Lessons Learned Review.”

These included the appointment of a migrants’ commissioner and the commitment to hold a series of “reconciliation events” with people affected, to “listen and reflect on their stories,” the Windrush Lessons Learned Review stated.

Subira Cameron-Goppy, who works as part of the Windrush Justice Clinic, providing support to victims, told CNN: “The UK government consistently double-down on their own mistakes and have failed to rectify their errors. These failures are a part of a continuation of the government’s hostile environment policy.”

In February 2023, the Conservative government published an assessment of the hostile environment policy’s impact between 2014 and 2018. The report concluded that the five nationalities most impacted by the policy were of Brown or Black heritage and all five were visibly not White.

Ramya Jaidev, a co-founder of Windrush Lives, told CNN that the hostile environment was not simply about “two or three specific policy errors but is the result of a series of increasing legislative push-backs that started in 1962 with the reduction of the rights of Black people. The attitude towards migrants is to phase them out. The Windrush Compensation Scheme is an extension of a hostile environment for Black and Brown people.”

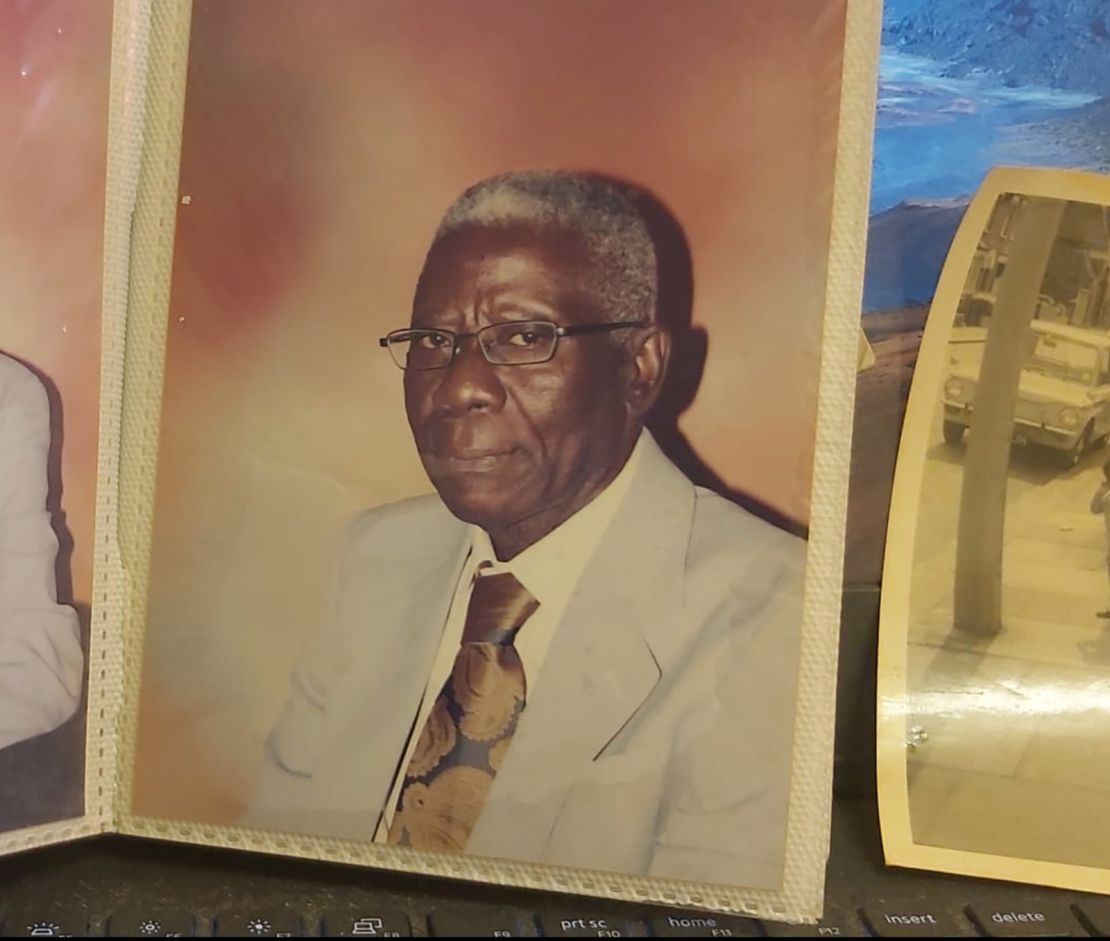

For some people, any compensation awarded is too late. Taiwo Abiona arrived in the UK in the late 50s from Nigeria. He worked as a postman for the Royal Mail, paid taxes and got a British passport in the 1960s. After the death of his wife, Stella, he went to renew his passport – but he was told he was no longer a British citizen, his son, Kemi Abiona, told CNN.

“They said a change of policy in the 70s meant he had to reapply then – we didn’t know he had to reapply – as far as we’re concerned he was a British citizen. When my dad lost his passport, he was devastated, and his health quickly deteriorated. He had no access to proper healthcare because he did not have the documents,” Abiona told CNN.

“While he was sick, we had been told to apply for a new passport through the Windrush scheme and we were told he would get compensation,” Abiona added. He helped his father fill in the application himself, because they could not afford a lawyer. “I kept telling my dad we will have money soon,” Abiona said.

In 2020, Taiwo Abiona received a letter saying he had indefinite leave to stay and that he would be able to apply for UK citizenship after a period of living in the UK – despite having lived there for nearly 70 years. “We were told compensation was on the way so we could get a carer for my dad – but it was too late,” Abiona told CNN. His father died two weeks after being told by the Home Office he could stay in the UK.

A week after his death, the Home Office paid £5,000 compensation to cover some of the cost of his funeral, Kemi Abiona said. He is now making a Windrush compensation claim through the Home Office to save up for a headstone for his father’s grave.