The rate of pregnant women dying of delivery-related causes in the hospital appears to have declined significantly – by more than 50% – across the United States in recent years, a new study suggests.

That decline, seen among more than 11 million hospital patients, came over a 14-year period from 2008 through 2021, according to the national study, published Thursday in the medical journal JAMA Network Open. But the decrease represents only in-hospital maternal deaths, not the nation’s overall maternal mortality rate, which has been on the rise.

“Much of the reporting on maternal mortality has focused on the increasing maternal mortality rates. As a result, this has led many people to believe that hospitals may be the main cause of maternal mortality,” study author Dr. Dorothy Fink, director of the Office on Women’s Health at the US Department of Health and Human Services, said in an email.

But the new study suggests that in-hospital maternal deaths may not be among the major drivers of the nation’s overall maternal mortality rate.

“This study specifically looked at?inpatient delivery-related outcomes and found a 57% decrease from 2008-2021,” Fink wrote.

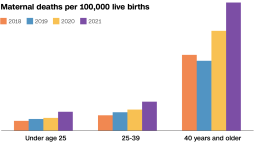

“This study also looked with greater granularity on the impact of race, ethnicity and age,” she said. “Mortality for American Indian women decreased 92%, Asian women decreased 73%, Black women decreased 76%, Hispanic women decreased 60%, Pacific Islander women decreased 79% and White women decreased 40% in the study period.”

In contrast, from 2008 through 2021, the new study found a rise in the rates of severe maternal morbidity, or unexpected complications of labor and delivery that can have significant acute or long-term consequences to a woman’s health. Severe maternal morbidity “is likely increasing due to the overall health of US women giving birth, including increases in maternal age, obesity, and preexisting medical conditions,” Fink said.

While the study suggests good news for maternal mortality rates among in-hospital deliveries, many maternal deaths still happen outside of the hospital setting, during pregnancy or postpartum.

It’s estimated that among pregnancy-related deaths, about 53% have occurred seven to 365 days postpartum, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 80% of all pregnancy-related deaths were determined to be preventable.

The new study “seems to contradict the data at the national level where maternal mortality is increasing, because most of the women don’t die in the hospital during childbirth; they die after they left the hospital?after childbirth,” said Dr. Jean Guglielminotti, an assistant professor at Columbia University Medical Center who was not involved in the new study but has conducted research on severe maternal morbidity.

“But to see a decrease in mortality during hospitalization for childbirth is good news,” he said. “It means that the quality of care has improved a lot.”

Not all expectant mothers, however, have access to such care. Across the US, about 36% of counties are designated as “maternity care deserts,” according to a report released last year by the infant and maternal health nonprofit March of Dimes. A county was classified as a maternity care desert if it had no hospitals providing obstetric care, no birth centers, no ob/gyns and no certified nurse midwives – which can drive maternal mortality rates.

A drop in hospital deaths, rise in morbidities

The new study included hospital data on 11.6 million deliveries. The researchers – from HHS and the health care company Premier Inc. – took a close look at patient discharge information from January 2008 to December 2021, including any deaths reported during hospitalization as well as complications or procedures indicative of severe maternal morbidities, such as heart attack, eclampsia or needing blood transfusions.

The data came from the Premier PINC AI Healthcare Database, which comprises more than 1,200 US hospitals and health systems but does not include the type of detailed clinical data found in electronic health records.

The hospital data showed that the rate of delivery-related deaths declined from 10.6 deaths per 100,000 patient discharges in the first quarter of 2008 to 4.6 deaths in the fourth quarter of 2021.

The data also showed an increase in deaths from 2020 through 2021, but the researchers found that could be associated with the Covid-19 pandemic.

Patients with a Covid-19 diagnosis “had a 13-fold increased odds” of death compared with those without Covid-19, the researchers wrote. And after they accounted for Covid-19 diagnoses in the data, they saw a consistent decrease in maternal deaths across the study period.

“This large national study found a decreasing trend of in-hospital delivery-related maternal mortality during 2008 to 2021, regardless of racial or ethnic group, age, or mode of delivery, likely demonstrating the impact of national and local strategies focused on improving the maternal quality of care provided by hospitals during delivery-related hospitalizations,” the researchers wrote.

The overall “decreasing trend” of in-hospital maternal deaths occurred despite increases in the prevalence of severe maternal morbidities among the patients, which climbed from 146.8 cases per 10,000 discharges in the first quarter of 2008 to 179.8 per 10,000 discharges in the fourth quarter of 2021. The biggest increases in severe maternal morbidity were among Pacific Islander, American Indian and Asian patients.

“Maternal mortality has been described as the ‘tip of the iceberg’ and maternal morbidity as a larger problem, ‘the base.’ For every individual who dies as a result of their pregnancy, it is estimated that 20 or 30 more experience significant lifelong complications that affect their health and well-being,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Compared with the prevalence of certain severe maternal morbidities in 2008, there was a higher prevalence in 2021 of sickle cell disease, high blood pressure, severe preeclampsia, substance use disorders, asthma, gestational diabetes, obesity and hemorrhage, the study found.

“The findings in the study are very consistent with what other studies have shown, particularly around trends in severe maternal morbidity,” said Dr. Zsakeba Henderson,?senior health adviser for the nonprofit National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in Boston, an expert on maternal and infant health inequities who was not involved in the new study.

For instance, she noted that?previously published CDC data?found that the overall rate of severe maternal morbidity increased almost 200% from 1993 to 2014.

“The take-home message is that we’re still seeing increases in severe maternal morbidity,” Henderson said of the new study.

“They found that there were certain risks associated with the increases. They noticed that cesarean delivery was a contributor, which is not surprising; the CDC reported on that as well previously. Comorbid conditions – or if they have another condition, if they had high blood pressure or are smokers or drug use – that increased the risk of severe morbidity,” she said. “But then the other thing is the disparities. There are persistent disparities, and they saw a statistically significant increased risk of death for American Indians, Blacks and Asians compared with white patients.”

Severe maternal morbidities are known risk factors of maternal deaths. The study found that American Indian, Black and Asian patients “had a statistically significant increased risk of death” compared with white patients when the data did not account for severe maternal morbidities.

‘What’s happening once mom leaves?’

The decline in maternal mortality suggests that some national strategies to improve maternal care – such as the nationwide initiative Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health and the CDC’s?National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives –?have been working, Fink said in her email.

“HHS continues to implement important initiatives focused on improving maternal and infant health. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently finalized two new hospital quality measures on severe obstetric complications and the rate of low-risk Cesarean deliveries, as well as a new?’Birthing-Friendly’ designation?that requires hospitals engage in such quality improvement activities,” Fink wrote.

“This new ‘Birthing-Friendly’ designation and other initiatives included in the?White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis?demonstrate HHS and the entire Biden-Harris Administration is prioritizing efforts to improve maternal health outcomes,” she said.

In general, the new study findings suggest that hospitals are “on the right track” when it comes to reducing death rates among people who are in the hospital to deliver a baby, said Dr. Mark Simon, chief medical officer at Ob Hospitalist Group, which provides ob/gyn specialists to hospitals.

“I think we’ve gotten better and more aware of addressing issues that occur in the hospital setting,” said Simon, who was not involved in the new study but has worked to help care teams implement maternal health protocols within hospitals.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Friday from the CNN Health team.

He thinks several factors could be playing a role in the decline of maternal deaths within the hospital, including a heightened awareness to follow maternal care protocols, greater awareness of racial disparities in maternal mortality and obstetric hospitalists playing larger roles in care.

But, he added, there is still more work to do to lower the maternal death rates outside of the hospital, especially after childbirth.

“What still concerns me about maternal health in this country is, clearly there’s an issue with postpartum care,” Simon said, referring to the large proportion of maternal deaths that happen after delivery.

“That’s an area that we need to continue to focus on. What do we do for our patients? What do we do for women in this country once they leave the hospital after delivering, making sure that we pay attention to their needs and concerns?” he said. “We might be doing a?better?job within the hospital, but what’s happening once mom leaves?”