Grasping a bouquet of roses, black headscarf tied tight and wearing a polka-dot dress, a middle-aged woman arrives in a nondescript, pink-walled hall in the Russian region of Chuvashia.

In shaky video complete with somber balalaika music, teenagers in white trainers, dignitaries in dark suits and men in military uniform assemble along the walls, their hands clasped in front of them.?

This scene looks like a gathering for a funeral – but it’s not. This is how Komsomolskaya School Number 1 is marking the opening of a new school desk, a so-called “hero desk” emblazoned with the face and biography of one of Russia’s war dead, once a pupil at this very school.

Ceremonies like this – dozens documented on schools’ social media pages and in local news reports across Russia - provide a glimpse into how a country at war tries to indoctrinate its youngest. It’s also part of a broader push in Russia to prioritize pro-war and patriotic teaching in educational institutions, a kind of insurance policy against any early seeds of dissent.

The desks are part of a pan-Russian initiative called the “New School Project” and are funded?by “United Russia,” a staunchly pro-Putin party.? As of early May, United Russia said there were more than 14,000 desks in 9,000 schools across the country.

CNN has seen images or videos from at least 26 regions across Russia where at least one desk has been opened at a local school. Local news reports suggest some schools use the desks to reward good behavior or good grades.

Jingles and jingosim

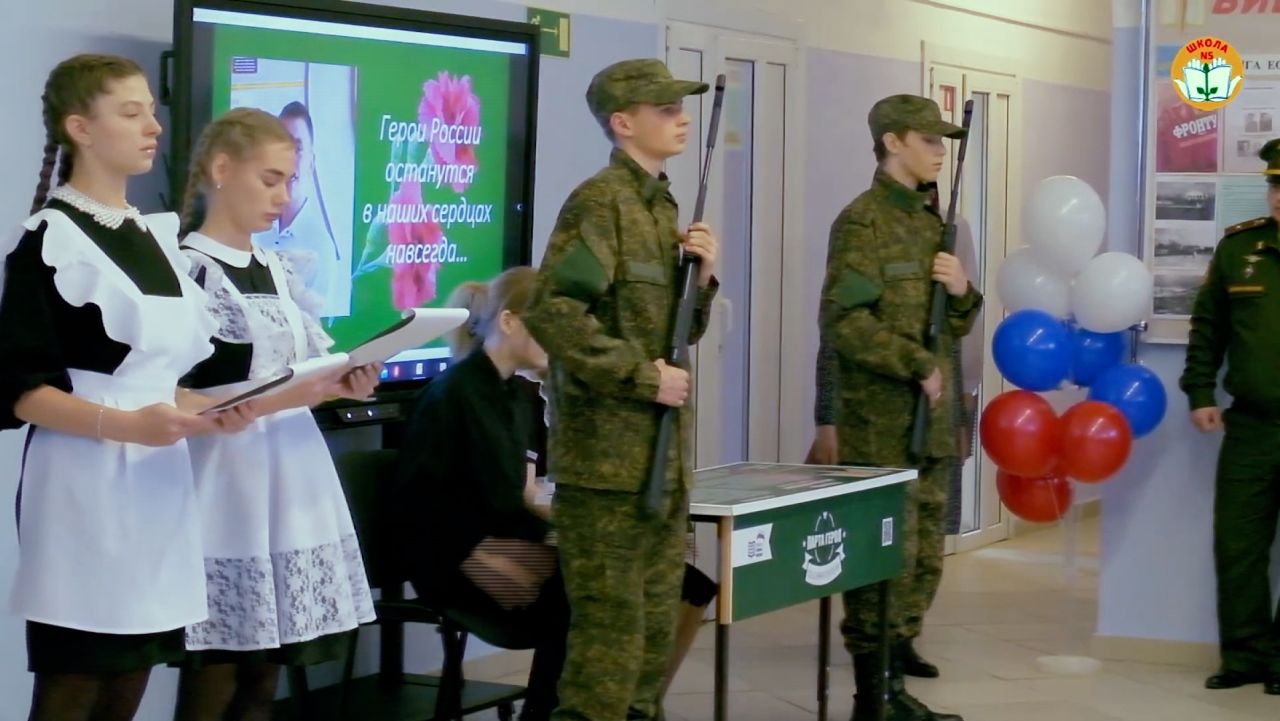

The ceremonies themselves vary, but the jingoism involved does not. Children in ceremonial military uniform sing the national anthem, carry flags and hammer their heels on the floor when marching. The scenes are more reminiscent of Red Square parades than the schoolyard.

In the video posted on a social media page of School No. 1 in Chuvashia, a young boy’s unwavering voice says, “Glory to those who lived in the treasured land. Glory to those who now live in it.”

Dressed in a green beret, white braid and matching gloves, another student, a young girl, says: “Today in the life of our educational institution is another significant event. The opening of the hero desk dedicated to our graduate Gennady Alexandrovich Pavlov, who died during a special military operation in Ukraine on February 27, 2022, protecting the interests of the fatherland.” ?

The woman in the polka-dot dress wipes her eyes as she walks to stand behind the desk. Her hand briefly touches the printed images of her son’s face.

The desks across the country are standardized: green, with military photographs, a biography, medals awarded (often posthumously) and the soldier’s date of death.?The desk in Chuvashia describes how Gennady Pavlov died just three days after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. He was killed during a military operation to capture the Antonov airport in Hostomel, part of Russia’s failed attempt to march on Kyiv at the start of the war.

Daniil Ken, who represents an anti-government union of teachers called the Teachers’ Alliance told CNN that the desk initiative was launched five years ago. Back then, “the project wasn’t that important for Russian society, but since the war in Ukraine started the government decided to use this project to commemorate the soldiers who died in Ukraine,” Ken said.? That could partly explain the number of desks, at more than 14,000, being so much higher than the number of deaths Russia has officially acknowledged in Ukraine.

The Russian Ministry of Defense has not released updates on its casualties since last September, when Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu said fewer than 6,000 Russian soldiers had been killed. Ukraine and the United States have given much higher Russian casualty estimates, although exact figures are elusive and are obscured by wartime secrecy.

Ken, who now lives in exile outside Russia, said the placing of a desk in a soldier’s former school is about making the war personal for Russian children. “You see his picture, his name, he was our pupil just several years ago,” he said, and for young people “it’s hard not to feel this painfully, and not to believe what the officials are saying in this moment.”

In January, Alena Arshinova, first deputy chair of the State Duma committee on education and a member of the United Russia party, said they had decided to “upscale this experience… Children should have the opportunity to learn history not only from the pages of textbooks… but also, in general, the whole environment in the school should contribute to the development of a child’s interest in studying the history of their country.”

Rewriting history

And yet the pages of history textbooks are another part of the Russian government’s educational propaganda effort. Olga, an English teacher in St. Petersburg, says she has seen textbooks which have now removed any reference to the fact that Kyiv was the first capital of Russia between the 9th and 13th centuries. “They want to say that there was only Russia, no Ukraine,” she said. CNN has changed her name for her safety.

Textbooks are also being updated to include more recent events. In April, Russian Education Minister Sergey Kravtsov unveiled a new 11th grade textbook which he said includes a section on “the reasons behind the special military operation,” the euphemistic term Russia uses for its war in Ukraine.

Olga says she has also seen history textbooks that contain quotes from both President Vladimir Putin and former President Dmitry Medvedev, now the deputy chair of Russia’s Security Council. They are portrayed, she said, as “the greatest leaders of modern Russian history, that they are the heroes. Students have to learn their words by heart and cite them in any place…. it was very ridiculous.”

It’s not just theory – there’s also a practical element to the government’s approach in schools. The ministry is promising to reintroduce basic military training, a throwback to Soviet times, into the curriculum, and some schools have already got started.

In a video posted by Russian state news agency RIA Novosti from a school in Simferopol, in Russian-occupied Crimea, a girl who appears to be around 10 years old races her classmates to take apart and reassemble a Kalashnikov rifle. She completes the exercise in 45 seconds. In Russia’s far eastern Sakahalin region, a local news report shows 8th graders completing the same exercise. “It’s useful for a man to learn military themes,” says one student. “It would be difficult in the army without training.”

And the government is stepping up efforts to ensure patriotism starts young. In September last year it launched a new initiative for all school ages – a lesson series entitled “Conversations about important things.”

The topics include “Symbols of Russia,” the “Blockade of Leningrad,” and “Traditional Family Values,” all providing opportunities for discussing the merits of the motherland, and in some cases directly pro-war sentiments. A special website offers videos and lesson materials for schools tailored for different age ranges, from six all the way up to 18.

“Our goal is to liberate Ukraine and we will achieve victory,” proclaims a World War Two veteran in one recent video to mark Victory Day in Russia.

‘I understood I wouldn’t stay much longer’

These lessons proved the final straw for Tatyana Chervenko, then a math teacher to 7th and 8th graders in a Moscow suburb. She said her first thought when she heard about them was that she would probably have to quit her job. “I understood I wouldn’t stay much longer.”

She persevered initially for the sake of her students. She had consulted a lawyer, who assured her the lessons were, under Russian law, voluntary, and so instead of these “Conversations” she ran extra math classes for her students. But she says she was being pressured by her school. She was given several reprimands, and at one point in October the police were called and she was arrested, she said, although let go the same day without charge. Finally, in December 2022, she was fired, she said.

Chervenko believes the level of propaganda in schools is the Russian state’s way of ensuring their power is “forever.” “Your children will also learn it and become adults, and fight, and support the motherland and so on,” she said. Her own 8-year-old son goes into school a little later on the days the “Conversations about important things” are scheduled, she said.

Teachers say the war has created a climate of fear, where you can’t speak your mind, even to friendly colleagues. Olga, the teacher in St. Petersburg, told CNN she was called to her school director’s office in the first month of the war, after expressing her opposition to the so-called “special military operation” to colleagues. “She warned me that if I continue, then she will have to appeal to a special body of the state. She meant the FSB,” she said, referring to Russia’s security agency.

Ken, of the Teachers’ Alliance, said the union now fundraises to pay fines for teachers who have been sanctioned under new Russian laws against “discrediting the Russian army.”

Russia’s Education Ministry has not responded to CNN’s request for comment on the desks and other changes in Russian schools since the war started.?

A window onto the war

The “hero desks” are not just a propaganda tool. They offer rare insight into the true cost of this war, something Russia has tried to hide.

Mikhail Stepanov, a Russian exile living in Virginia, has dedicated his time to uncovering the true scale of Russian losses through his website Poteru.net. He spends his days scraping the internet for any signs of Russian casualties posted in chat forums, social media and official channels – and very quickly the desks became one of his most important sources.

“When you are on the lookout for photos of the killed and you use Google, or Yandex images or Vkontakte, you enter the guy’s name and word ‘killed’ and often you get his ‘hero desk’,” said Stepanov.

“It just scares and instils terror in me that in a couple of years these children will leave school with that level of propaganda, having had the only thought instilled in them that going to war without complaint is the only contribution they can make and to die for the country.”

Among the estimated 500 desks he has uncovered, Stepanov says a small number were for Wagner fighters, adding weight to recent evidence that the group was not as “private” a military company as it claimed. One desk, for a 21-year-old from Khabarovsk in Russia’s far east, says he died in August 2022 in “Artyomovsk” (Russia’s preferred name for the eastern Ukrainian city of Bakhmut). Among his military honors listed is a medal “for bravery and courage” from Wagner.

Ken worries about the long-term impacts of this propaganda drive. “This is millions of students, citizens of the country, that you can gather in one place, tell them what you want, and someone will believe you,” he said.

“It is something so dangerous for the pupils and it will have an impact on Russian society for decades.”