Ken McCullick died in an emergency room on August 12, 2021.

“I got lucky and there was this young nurse … I was one of her first CPR patients, and she would not give would not give up and saved my life.

“I’m grateful for that,” McCullick said, his voice choked with emotion at the memory.

The 66-year-old musician from Brooksville, Florida, said his heart stopped after he got the blood thinner heparin in the hospital.

Heparin is made from pig intestines and contains a sugar called alpha-gal that McCullick is deathly allergic to, although neither he nor his doctors knew it at the time.

“I flatlined and died on the table,” McCullick said, adding that it took seven minutes to get his heart started again.

Alpha-gal syndrome is a reaction to a sugar found in red meat and dairy products, and it’s caused by the bite of a lone star tick. It may now be the 10th most common food allergy in the United States, affecting up to 450,000 people, according to estimates published Thursday by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.?It is also one of the least recognized.

Lack of awareness, lack of diagnosis

Scientists have only recently begun to understand alpha-gal syndrome.

Lone star ticks, and perhaps other kinds of parasites, transmit a sugar known to scientists by its unwieldy formal name: galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, or alpha-gal.

“We think that they have an enzyme in their saliva that can produce alpha-gal,” said Dr. Scott Commins, associate chief for allergy and immunology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, who has spent his career researching alpha-gal and is a co-author on the new studies published today by the CDC.

When these ticks bite someone, the alpha-gal passes through the skin, which has its own immune sentries waiting to pounce on foreign invaders. Being exposed this way appears to put the body on high alert for this sugar, which is found in non-primate mammals and in products made from them. People with alpha-gal syndrome must often avoid red meat like beef, pork and lamb, dairy products and a slew of less-obvious products like gel capsules and sometimes makeup.

People can live with alpha-gal by adjusting their lifestyle — but that’s only if they know they have it. Getting a diagnosis can be difficult because many doctors aren’t aware of the syndrome.

A study published Thursday in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report surveyed 1,500 doctors and nurse practitioners in the US and found that 42% said they’d never heard of the allergy. Another third of respondents said they were not confident about their ability to diagnose or manage a patient with alpha-gal allergy.

Surveys of alpha-gal patients have found that most have a significant delay between their first symptoms and their diagnosis.

McCullick, who thinks he got alpha-gal syndrome from a tick he pulled off his forehead in 2018, wasn’t diagnosed until 2022.

Alpha-gal isn’t like a typical food allergy, in which the physical reaction to an offending food starts seconds to minutes after eating it.

Instead, people with alpha-gal allergy tend to become ill four to six hours after having red meat or dairy, so they don’t always connect their symptoms to what they’re eating. Reactions can include hives, shortness of breath or even life-threatening anaphylaxis.

“I went to bed every night not knowing if I was going to wake up in the morning. And every time I couldn’t catch my breath and every time my heart skipped a beat, I didn’t know what was going to happen,” McCullick said.

“The future didn’t seem very bright, and I can relate it to maybe being a soldier in a foxhole with shells coming down all around. You just don’t know when your last breath is going to be, and it was psychologically devastating, actually. And that’s not just me; there’s thousands and thousands of cases just like mine,” he said.

Diagnoses on the rise

Researchers haven’t had a good idea how many Americans might have alpha-gal syndrome.

Until 2022, one commercial lab ran most alpha-gal testing in the US: Viracor in Lenexa, Kansas. For the new study, epidemiologists at the CDC analyzed anonymous testing data from this lab for blood tests run from 2017 through 2022.?Providers ordered nearly 300,000 tests for alpha-gal during this period, and 30% of them — roughly 90,000 — were positive.

Adding those test results to the results of earlier studies, the study authors deduced that there were 110,000 suspected cases of alpha-gal syndrome diagnosed in the US from 2010 to 2022.

With the lack of awareness among health care providers, the researchers adjusted their data under the assumption that between 20% and 78% of cases probably go undiagnosed. This led to them to estimate that between 96,000 and 450,000 Americans may have been affected by alpha-gal syndrome since 2010.

The numbers stunned Commins. “The number of potential cases is far beyond what we thought,” he said.

“If the projection and estimate of nearly 450,000 cases is even approximately correct, this is the number 10 allergy in the country behind sesame, which is number nine and affects roughly half a million people,” Commins said.

And the numbers weren’t steady over time. “Every year, we see an increased number of suspected cases that are captured in this lab-based surveillance,” said study author Dr. Johanna Salzer, the epidemiology team lead for rickettsial diseases at the CDC.

Salzer said it’s unclear whether cases are going up because of increased awareness and testing for the syndrome or for another reason, such as tick populations flourishing in the higher temperatures caused by climate change.

“I think it could certainly be both,” Salzer said.

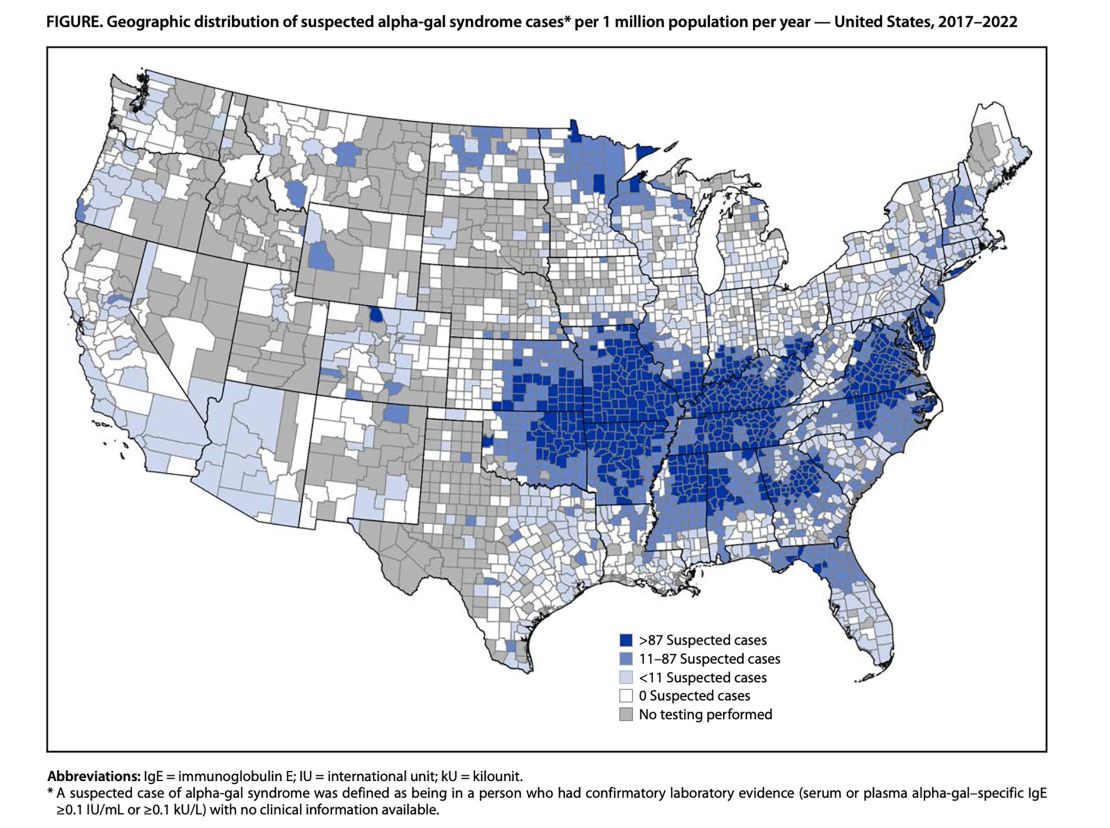

Salzer and her team also mapped the locations of the positive tests and found that they were concentrated in a belt of states in the middle of the US that spans the South, Midwest and Mid-Atlantic regions. This is much the same region where lone star ticks are known to cause other diseases such as the bacterial illness ehrlichiosis.

‘This disease doesn’t have to be deadly’

Before McCullick knew to avoid certain animal products, he was rushed to the emergency room repeatedly with life-threatening allergic reactions that caused heart palpitations, shortness of breath and dangerously low blood pressure. Often, he was treated for heart attacks.

Alpha-gal also affects the way his body processed cholesterol, clogging the arteries around his heart.

Sometimes, just breathing in a place where someone is cooking meat, like a steakhouse, can cause a reaction, he said.

“I would eat some ice cream, and it would hurt my throat and my esophagus down my chest so bad. They felt like a charley horse that would not go away,” McCullick said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“And then it gives you severe heartburn, feels like a hiatal hernia,” he said. “Then it gets down in your stomach, and it feels like a roll of barbed wire the rolling around in your intestines.”

This cycle of eating and anaphylaxis continued until McCullick spoke to an agent from his health insurance company. After reviewing his records, the agent told him that the pattern of hospitalizations looked familiar.

“He said, ‘you know, you sound like what happened to me.’ He said, ‘I’m allergic to beef and pork. And you should get checked out to see if you’re allergic to beef or pork,’ ” McCullick said.

A lightbulb went off.?He realized he was getting sick every time he ate red meat. After researching online, he was convinced, and he saw an allergist who made the diagnosis.

“So my diagnosis was by chance, basically, and with a lot of research on my own and a lot of help from friends,” McCullick said.

“This disease doesn’t have to be deadly if we just know about it,” McCullick said. “A lot of people could be saved just from the knowledge that needs to get out there.”