In July 1963, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, teenager Shirley Reese joined a peaceful protest here in Americus, Georgia, with other young Black girls.

Together, they walked to the Martin Theater and tried to buy movie tickets at the window designated for White customers. The police were called, according to Reese. But few could have predicted what would happen next.

“All of you are under arrest,” Reese remembers the officer telling the children, all of whom, she said, were between the ages of 12 and 15.

And then, without much ceremony, several of the girls were rounded up and taken to a stockade in Leesburg, Georgia, 23 miles outside of town. They would remain jailed there nearly 60 days.

To their parents and loved ones, the girls had simply vanished. It would be weeks before anyone would learn what happened to them, Reese said.

Reese, now 75, returned to the stockade with CNN’s Randi Kaye to mark the 60th anniversary of the girls’ arrest.

“It was filthy,” she recalled, surveying the small cell. “Some blankets was in there with bloodstains on it.”

The stockade was surrounded by thick woods, and in the summer heat it was extremely humid in the cell. The girls were kept there without beds, a working shower or toilet, she said. And when night fell, they were plunged into the inky darkness of rural Georgia.

“We couldn’t see each other,” Reese recalled. “So, you know, you hear a lot of sniffling and stuff like that, but nothing, nobody could do nothing.”

‘Children took the front line’

Americus is a small town whose name evokes the promise of this country. But for Black residents in the 1960s, the name had long belied a dark, racist reality.

During the Civil Rights Movement, children often protested in the town because it was thought they were less likely to face retaliation. Civil rights groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized youth-led sit-ins and marches across the South to demand an end to segregation.

“(Adults) didn’t participate a lot because they had to work and take care of families,” said Carol Barner Seay, one of the Leesburg Stockade Girls, as they became known. “And if they got involved in any part of it, they would have lost their jobs. How would they survive?”

“It was the children that took the front line.”

But things changed during the summer of 1963. A few days before Reese was taken into custody, Seay, then 13, was also arrested during a march in Americus. She told CNN she remembers demanding an explanation from officers who led her away.

When asked if the officers ever explained why she was detained, Seay gestured to her brown skin as if that were reason enough to jail a child.

“Look at me … somebody owe me an explanation?! They going to give me an explanation?!”

Seay said she was briefly moved to a jail in nearby Dawson, Georgia, before eventually being taken to the Leesburg Stockade.

“We had no idea where we were,” she said. “We didn’t know we was in Leesburg.”

If the girls had been told their whereabouts, Seay said, it likely would have evoked even more fear.

“Leesburg was known as Lynchburg … They lynched Black people on the trees,” she said.

For almost 60 days, the girls were unable to bathe, forced to remain in the clothes they were wearing when they were arrested. Reese said they were fed hamburgers that were delivered by a stranger daily. They used the hamburger wrapping for toilet paper, she said.

“I’d miss my mom. I missed my siblings … my mother’s good food,” Seay said.

We didn’t think we would ever get out, Reese said.

“We started praying together,” Reese said. “So, we would gather some time and pray. And then we would pray individually, and cry individually.

The Stolen Girls

Reese and Seay remember the day, nearly a month into their imprisonment, that a White photographer showed up. Danny Lyon was a 21-year-old photographer with the SNCC.

“(Lyon) come around the building, I said, ‘Who are you? What’s your name?’” Reese recalled. “He said, ‘Be quiet!’”

Then she noticed his camera.

“I said, ‘Take my picture, right here!’” she recalled. “I knew if he was there taking pictures and they were going to go somewhere. So, that’s why I wanted to make sure that he got me.”

Seay remembers him signaling to the girls with the peace sign and a single word: Freedom.

“If you was living segregation, born in segregation, slept segregation, ate segregated, went to church segregated, freedom meant everything to you,” she said.

“You wouldn’t have a reason to use that word if you was (White). But if you was my color, it meant a lot. OK? That was a symbol to us, that he was there to do us no harm.”

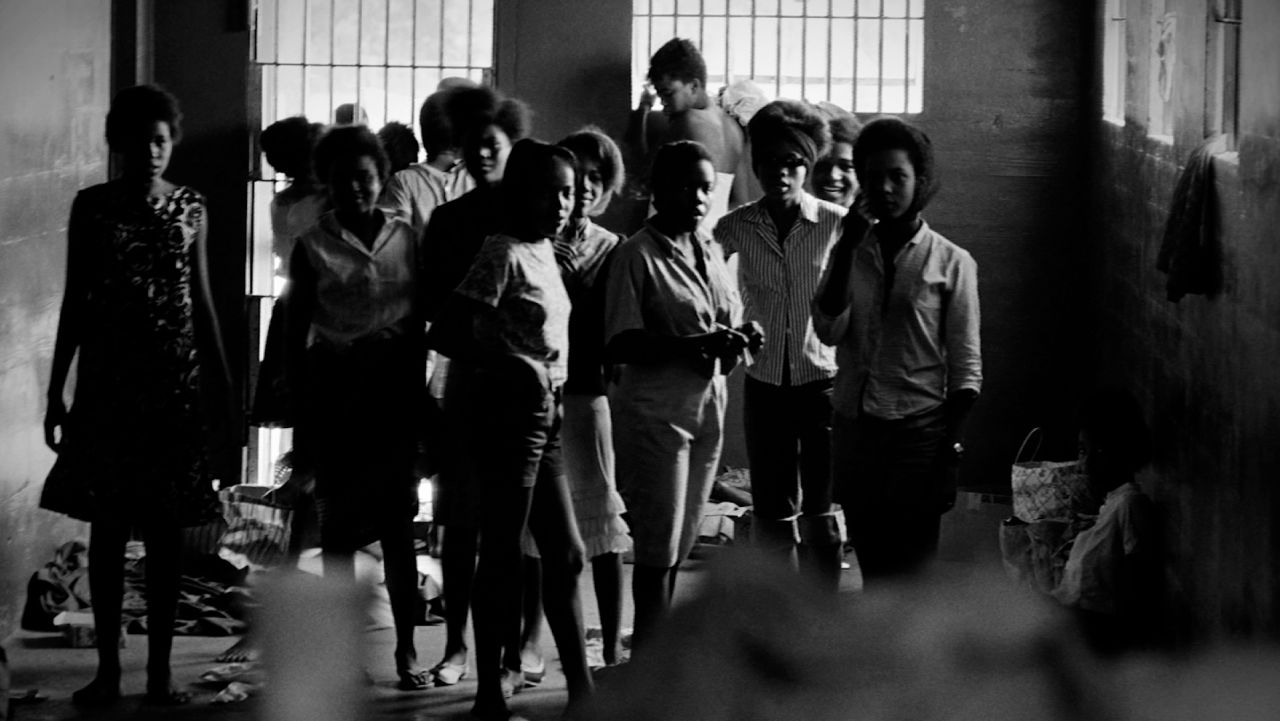

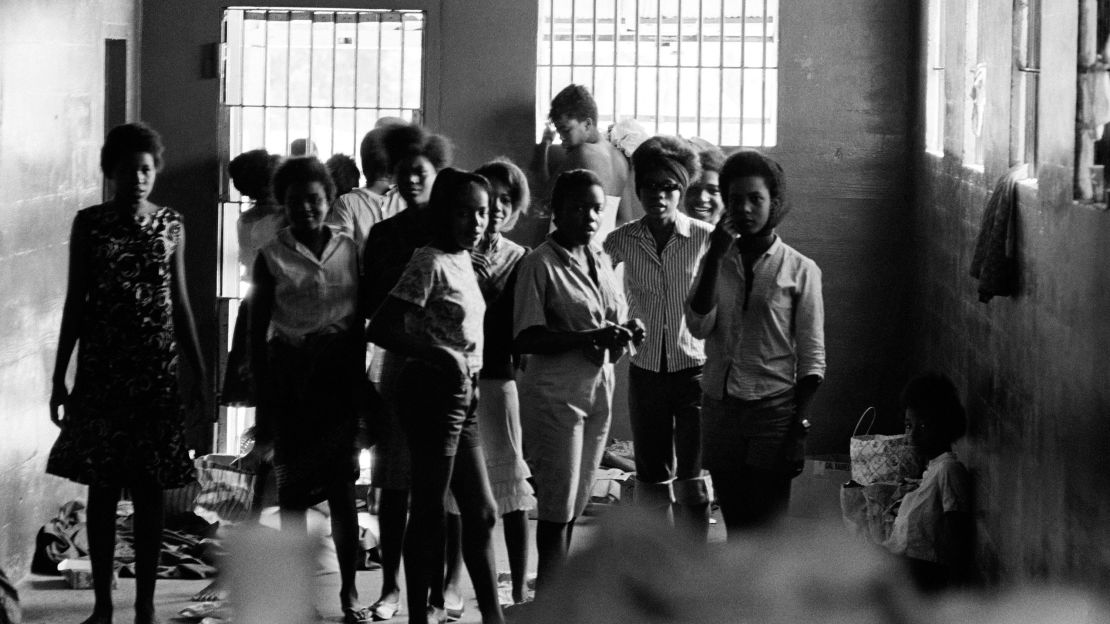

At first glance, the photos Lyon took that day seem joyful. The girls, still wearing the dresses and they donned for the protest, smile at the camera as if to signal to the families desperately searching for them that they were OK.

But a second look reveals they were surrounded by bars.

That juxtaposition – of smiling children in their Sunday best standing behind bars – captured national attention. Lyon’s photos were published in the SNCC newspaper and Jet Magazine; the press dubbed them The Stolen Girls. The photos were eventually seen by New Jersey Senator Harrison A. Williams who entered the images into the Congressional Record.

Amid the outcry, the girls were freed in September 1963. They were never charged with a crime.

But the story of the Leesburg Stockade Girls was soon eclipsed by the relentless drumbeat of racist violence in the American South. The same week the girls were released, Ku Klux Klan members bombed a church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four little girls.

For years, many of the Leesburg Stockade Girls refused to speak about their harrowing experience. Some of the girls and their families remained in Americus, Reese said, and kept their heads down to avoid further retribution.

But after being released, Reese said she struggled to process all that had happened to her.

“It was just like I didn’t … I didn’t exist,” she said.

Decades later, Reese said she now feels the experience made her stronger. She would go on to earn a master’s degree, as well as her Ph.D.

“My mother wanted me to get an education. And as strong as I was at that time as a child when I there, I was broken … I really didn’t want to do anything. But I had to refocus my mind,” she said.

Seay said she still remembers the moment she reunited with her family.

“My mom, you know, she hugging on me,” she said. “We’d been gone for two months and we haven’t had a bath.”

She said the time she spent in the stockade “should have made me bitter. But I stand here today to tell you it made me better and it continues to make me better.”