The 2024 Olympics are fast approaching and as athletes gear up for one of the world’s most prestigious sporting events, one entrepreneur has a different idea of what “faster, higher, stronger” – the former motto of the Games – might represent.

The Enhanced Games says it is an “alternative” to what it calls the “corrupt Olympics Games.”

Athletes competing at the Enhanced Games will be free to use performance-enhancing drugs, they won’t be tested and will be under no obligation to declare which substances they have taken in order to compete.

That’s quite a contrast to the Olympics’ doping protocols. The International Testing Agency (ITA) will be responsible for looking after Paris 2024’s anti-doping program. Six years ago, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which oversees the Olympics, delegated its entire clean sport program to the ITA. However, historically the Olympic Games have been dogged by a series of doping and kickback scandals.

When approached for comment on the Enhanced Games and allegations of corruption, the IOC told CNN Sport that “the idea does not merit any comment.”

‘Danger to health, to sport’

CNN Sport interviewed a number of experts in the field of doping for this story, who expressed concern that the Enhanced Games was an extremely dangerous proposition.

Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov, who exposed Russia’s state-sponsored doping program – a massive, years-long effort which benefited more than 1,000 athletes between 2011 and 2015 – said that the Enhanced Games is a “danger to health, to sport.”

Whether the Enhanced Games will ever take place remains an open question, but the very idea is drawing considerable blowback from leading anti-doping officials and sporting organizations.

The Enhanced Games is the brainchild of businessman Aron D’Souza. He is also the founding editor of “The Journal Jurisprudence,” a quarterly publication on legal philosophy, according to his website, which also describes him as an “avid athlete.”

Recently, D’Souza told CNN Sport he has “signed term sheets with prominent venture capital firms” in relation to the Enhanced Games and is “waiting on the lawyers to finish long-form drafting.” He also said that a funding announcement is planned for early December.

Although not legally binding, term sheets are a serious expression of intent by both sides, setting out the broad principles of an agreement.

D’Souza believes what he calls a “science-driven” competition is the next step in the evolution of sport, suggesting that the absence of drug testing will level the playing field.

According to a 2020 study from Raphael Faiss, Research Manager at the centre of Research and Expertise in anti-doping sciences at the University of Lausanne, data from the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) suggests less than 2% of athletes dope.

However, Faiss told CNN Sport the number of athletes taking performance-enhancing drugs is likely significantly higher; his research, based on two international major athletic events in 2011 and 2013, suggests the figure could be between 15 to 18%.

Faiss and his team compared athletes’ blood results collected by WADA-accredited labs to values from healthy adults, as well as doped and undoped athletes; the closer the values are to those of subjects to whom erythropoietin (EPO, which is used in blood doping) had been administered, the higher the chances that they’re actually doping.

This analysis, Faiss said, is not proof of doping, but is a “robust way” of analyzing the data, allowing scientists to make an estimate for doping prevalence, as well as targeting athletes most likely to be doping.

In written comments to CNN Sport, WADA said: “Determining the level of [doping] prevalence is a priority for WADA and something that is being addressed,” explaining that, since 2017, a “prevalence working group” has been established to “determine if strategies, reliable methods and tools can be developed to adequately assess the prevalence of doping in sports.”

WADA told CNN Sport that the group has delivered “several recommendations and guidance to WADA but not the final ones yet.”

WADA has reservations about Faiss’ study and pointed to the “complexity of trying to measure [doping] prevalence,” highlighting that reports have “greatly varying results.”

The anti-doping organization added: “No single method will give a definitive prevalence figure for doping in all sports or even a single discipline.”

“Comparing the 15-18% found in the Faiss study with the global anti-doping system’s testing figures isn’t comparing like with like. The 2% quoted includes all sports and all countries and is not a useful guide for estimating prevalence.

“In any event, a single rate for all of global sport is not particularly helpful given the differences that occur between sports and countries – it would almost certainly overestimate some sports and countries, and underestimate others.

“The Faiss figures, on the other hand, refer to one sport, at two points in time, more than a decade ago. It is not useful or fair to compare these two figures.”

Editor’s note: You can find WADA’s full statement at the bottom of this article.?

‘A dangerous clown show’

Travis Tygart, the Chief Executive Officer at the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), told CNN Sport that the idea of an Enhanced Games is “farcical … likely illegal in many [US] states” and “a dangerous clown show, not real sport.”

Substances such as anabolic steroids – which help to build muscle mass by enabling athletes to train harder and recover quickly from strenuous workouts – are classified as a Schedule III drug by the US Drug Enforcement Administration.

When asked whether anabolic steroids will be allowed at the games and whether athletes would be tested for illegal drugs such as cocaine, D’Souza told CNN Sport that “we will not be drug testing at the games.”

He added: “We do not propose to regulate what athletes use.”

Anabolic steroids may be prescribed by a licensed physician for the treatment of certain conditions such as testosterone deficiency, but if used in the US without a prescription from a licensed physician, a first conviction could result in a one-year prison sentence and a $1,000 fine.

But that isn’t the only potential legal jeopardy the Enhanced Games faces, according to American lawyer Jim Walden, who represents Russian whistleblower Grigory Rodchenkov.

“If you look at the Enhanced Games website, it’s almost as though they’re advertising their disregard of the law,” Walden told CNN Sport.

“They wrap themselves up in what I will call the cloak of legitimacy by using phrases like body autonomy and coming out as an enhanced athlete.

“I hope they’re thinking hard about how they’re going to pull this off in the world in which the FBI has a specific unit that is called the Sports and Gaming Initiative that’s focusing on these very issues.”

The Sports and Gaming Initiative was developed to “protect athletes and sporting institutions in the United States from criminal threats and influences,” according to the government website.

The initiative works in partnership with sports leagues and governing bodies, international law enforcement and independent watchdog groups to tackle crimes such as fraud, doping and match-fixing; criminal activities, it says, “degrade the integrity of sports and competition and erode public confidence in these cherished institutions.”

“The use of doping substances is not acceptable in modern sports,” Rodchenkov said in his written comments to CNN.

“Promotion and advertising of banned substances is against sport rules and moral, letter and spirit.

“It might bring an extreme harm to young generation[s] of athletes who mistakenly could believe in benefits of [the] Enhanced Games.”

Rodchenkov, the protagonist of the Oscar-winning Netflix documentary Icarus who is currently under FBI protection, also believes that the Enhanced Games’ organizers “might get investigated […] under the Rodchenkov Act.”

The Rodchenkov Anti-Doping Act, named after the whistleblower, allows the US to impose criminal sanctions on individuals involved in doping activities at international events.

However, the Rodchenkov Anti-Doping Act does not apply to sporting events that don’t adopt the WADA code, which the Enhanced Games wouldn’t do.

Rodchenkov also added that WADA athletes could not have any affiliation or contact with so-called enhanced athletes, or they would risk being charged under Article 2.10 – “Prohibited Association by an Athlete or Other Person” – of the World Anti-Doping Code.

USADA’s Tygart also told CNN Sport: “No one really wants our children growing up idolizing unbridled drug use in sport, even if some profiteers think otherwise.”

D’Souza insists his motivation for founding the Enhanced Games isn’t financial. If he had wanted to make more money, he says he’d continue to be a “quiet, mild-mannered venture capitalist.”

“I do think fundamentally that consumers want this [the Enhanced Games] and athletes want this because if you go to the cinemas, no one’s interested in histories in the past anymore,” said D’Souza.

“They’re interested in superheroes and technology in the future. And this is literally what we are bringing to a reality.”

‘The dirtiest Olympics in history’

According to Pierre de Coubertin – the founder of the modern Olympics – “for every man, woman and child, it [sport] offers an opportunity for self-improvement.”

Except historically, many athletes competing in the Olympics have taken the idea of self-improvement too far, notably at London 2012, which Rodchenkov has previously called “the dirtiest Olympics in history.”

When the ITA concluded its re-analysis program for the London Games, it found 73 anti-doping rule violations, which led to the withdrawal of 31 medals and reallocation of 46 Olympic medals across the sports of athletics, weightlifting, wrestling and canoeing.

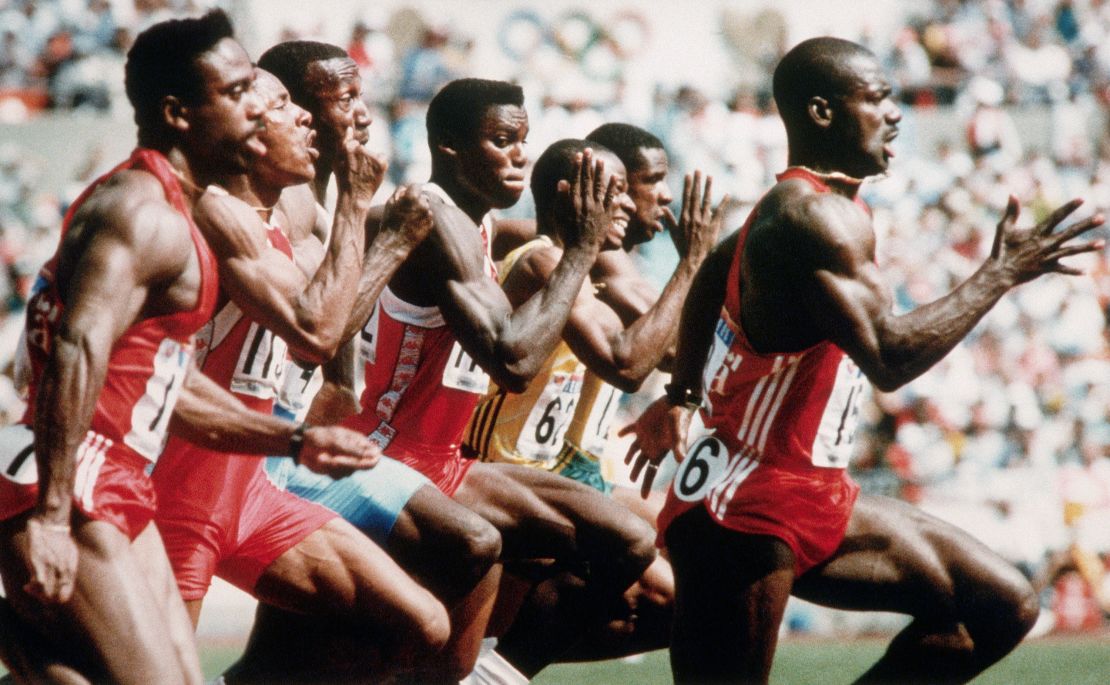

Doping has been an issue at the Olympics throughout the event’s history, and the 100-meter final at the 1988 Games has become one of the most infamous and controversial moments in sporting history.

Six of the eight finalists – notably the winner, Ben Johnson – who lined up on that September day in Seoul 35 years ago would fail drug tests themselves or be implicated in drug use during their careers.

Despite some athletes continuing to cheat, global antidoping efforts remain ever-present, according to the testers.

Recent out-of-competition (OOC) testing data published by the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) highlights positive results from steps being taken to keep “elite podiums and finals clean,” according to the anti-doping organization.

Data focused on OOC testing ahead of last year’s World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon, shows how resources and testing are targeting those athletes most likely to win medals and make finals.

Whilst only 39% of the athletes in Eugene had three or more OOC tests in the 10 months leading up the event, 81% of top-eight finishers had three or more OOC tests.

Yet the cat and mouse game between testers and athletes using banned substances continues.

“It’s mostly about the question of timing and targeting the right athletes,” said Faiss.

Given that athletes have their blood values regularly monitored, it is “getting more difficult for athletes to use high doses [of drugs such as EPO], but they would still be using micro dosing.”

By taking EPO late at night and drinking enough water, the substance would not be detected in athletes the following morning, according to Faiss, though athletes suspected of blood doping could be tested in the middle of the night.

“Athletes are actually getting back to very simple ways of doping with steroids,” he said, adding that “EPO is quite simple to use, but still tricky to detect.”

Athletes “use the drugs that are actively working.”

When it comes to new substances such as Roxadustat – the drug that two-time grand slam champion Simona Halep has recently been given a four-year ban for taking, although she denies ever knowingly or intentionally taking any prohibited substance – Faiss said athletes “are likely to use substances with a very short half-life in [the] body that are mimicking processes of the oxygen carrying improvements through the EPO channels.”

Roxadustat has an elimination half-life of 10-16 hours, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Athletes are “seeking to find substances where the [half-life] time window is very short, to make sure that if they are not tested at the right moment, they won’t be caught,” said Faiss.

‘Challenge for sporting competition’

Michele Verroken, the founding director of consultancy group Sporting Integrity, believes an antidoping system is required that will “give a lot more credibility, a lot more immediacy to verifying results, if we’re going to keep the hearts and minds of athletes.”

Verroken also questions what’s stopping an athlete from cheating if they only get caught 10 years after the event, or not at all. Under the World Anti-Doping Code, there is a 10-year statute of limitations on samples taken from 2015 onwards.

Verroken told CNN Sport that the Enhanced Games is “setting a really interesting challenge for sporting competition.”

Not unsurprisingly, many sporting bodies have condemned the event. The Australian Olympic Committee called it “dangerous and irresponsible,” saying that “the world needs better than this.”

UK Anti-Doping (UKAD) said it “is extremely concerned by the concept of an Enhanced Games,” adding that “there is no place in sport for performance enhancing drugs, nor the Enhanced Games.”

UKAD’s Director of Operations, Hamish Coffey, told CNN Sport that the Enhanced Games sets a “hugely dangerous precedent,” expressing concern over the kind of messaging the event sends to the next generation of athletes.

‘Very accomplished athletes’

When CNN Sport spoke to D’Souza shortly after the proposed event’s announcement, he said that 368 athletes had enquired about the Enhanced Games and more had messaged via social media.

The organization’s Chief Athletes Officer and former Olympian Brett Fraser, who swam for the Cayman Islands at three Olympic Games, told CNN Sport that “very accomplished athletes” at the level of Olympic finalists have reached out “to understand more about how the first Games will take place and how they can become involved.”

Fraser added that Enhanced Games organizers “already have an Olympic medallist” for their athlete commission, though he didn’t specify who that was.

He also said there has been “a lot of positive feedback and a lot of acceptance and excitement from younger generations.” Nonetheless, none of the athletes appear prepared to speak publicly at this stage.

For those who do want to compete, the Enhanced Games would be an annual event with five categories – track and field, swimming, weightlifting, gymnastics and martial arts.

The huge cost of hosting an Olympic Games is no secret, with countries often striving to create bigger and better spectacles by blowing their budget.

Tokyo 2021 had the largest Olympic sports program in history, with 33 sports competitions in 42 venues culminating in 339 medal events.

The Covid-impacted Games were delivered with a final expenditure of $13 billion – almost double the $7.3 billion that was originally forecast. Meanwhile, keeping the IOC’s philosophy of “lower-impact Games” in mind, 95% of venues will be pre-existing facilities at the Paris 2024 Olympics.

D’Souza said the Enhanced Games will focus on fewer sports, reuse existing infrastructure and fund the event through the private sector to “deliver a high-impact yet cost-efficient games” so profits can be shared with the athletes.

He added that the Enhanced Games is looking for a seven-figure prize pool for any athlete potentially breaking Usain Bolt’s 100-meter world record of 9.58 seconds.

“I’ve had conversations with people who are top-10 sprinters in the world who are going to the next Olympics, and they said […] if there’s a million-dollar prize to break the 100m world record, I’ll be there,” said D’Souza.

Universal basic income and mental health support to athletes will also be part of an “enhanced athletes programme.”

When asked who would take responsibility if an athlete competing at the Enhanced Games were to suffer fatal consequences, D’Souza told CNN Sport that “our athletes at the games will be the most monitored athletes in history.”

He said: “We will focus on athlete safety by mandating athletes have pre-competition full-system clinical screenings including blood tests and EKGs.”

“This will ensure that athletes are healthy to complete and not at risk of major health complications.”

D’Souza also said that athletes will sign waivers in order?to compete.

As it stands, no venues are officially in place to host the event and D’Souza admits its scale will be dependent on funding and media partnerships.

“We’re in commercial negotiations with venues and media partners at the moment,” added D’Souza, who said the first Enhanced Games will be at a university campus or a similar facility in the south of the US and that a number of trademarks have been filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

‘Undermine the very purpose of sport’

Elite performance coach Trevor Painter, who has worked with a number of Olympic and international sprinters and middle-distance runners, said he would “never” coach an athlete taking performance-enhancing drugs because it would go against his morals as a coach.

“Having been involved with many athletes that have lost in many ways to the cheats, I won’t be engaging with [the Enhanced Games],” Painter told CNN Sport.

If it goes ahead as planned in December 2024, D’Souza insists that the Enhanced Games will unlock the potential of humanity.

But according to John William Devine, Senior Lecturer in Ethics, Sport and Exercise Sciences at Swansea University in Wales, the Enhanced Games will make sporting competition more unfair than it already is and even “undermine the very purpose of the sport in question.”

Devine told CNN Sport that “performance-enhancing drugs don’t actually lead to better athletic performance. They obscure athletic performance.”

He added that, although the Enhanced Games may look very similar to the Olympics, the nature of the activity will be different, raising the question: “To what extent is drug-assisted performance reflective of the athletes’ sporting excellence?”

WADA response in full:

Determining the level of prevalence is a priority for WADA and something that is being addressed. That is why we set up a?Working Group on Doping Prevalence?in 2017. Measuring doping prevalence is a difficult and complex process. Through its work, the group found a huge variance across the many prevalence studies that have been carried out, leading it to publish guidelines on how to improve the quality of measuring prevalence. WADA is currently developing a tool that Anti-Doping Organizations can use to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs.

WADA is well aware of the [Faiss] study. Indeed, one of the contributors, Prof. Martial Saugy, is a member of the Working Group. This study is one of many that helps to inform the Group’s work. It is a very narrow study. It looks at two events, in a single sport, held 10 and 12 years ago, using just one method of measurement (the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP)). As far as I am aware, there is no comparable data from more recent World Championships in the same sport. Given its limited scope, it is important that this study be analyzed within the wider context of other studies and not be taken in isolation.

This study also highlights the complexity of trying to measure prevalence. It is the third published paper that sought to measure prevalence at the 2011 Athletics World Championships. Each reported greatly varying results.

The fact is no single method will give a definitive prevalence figure for doping in all sports or even a single discipline. Results will always come with caveats and margins of error and will be based on a variety of methods, including self-report questionnaires, analytical methods (like ABP and testing data) and other methods to give a more rounded estimate of what the most likely figure would be.

Comparing the 15-18% found in the Faiss study with the global anti-doping system’s testing figures isn’t comparing like with like. The 2% quoted includes all sports and all countries and is not a useful guide for estimating prevalence. In any event, a single rate for all of global sport is not particularly helpful given the differences that occur between sports and countries – it would almost certainly overestimate some sports and countries, and underestimate others. The Faiss figures, on the other hand, refer to one sport, at two points in time, more than a decade ago. It is not useful or fair to compare these two figures.