A new study projects that global fertility rates, which have been declining in all countries since 1950, will continue to plummet through the end of the century, resulting in a profound demographic shift.

The fertility rate is the average number of children born to a woman in her lifetime. Globally, that number has gone from 4.84 in 1950 to 2.23 in 2021 and will continue to drop to 1.59 by 2100, according to the new analysis, which was based on the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2021, a research effort led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. The study was published Wednesday in the journal the Lancet.

“What we are experiencing now, and have been experiencing for decades, is something that we have not seen before in human history, which is a large-scale, cross-national, cross-cultural shift towards preferring and having smaller families,” said Dr. Jennifer D. Sciubba, a demographer and author of “8 Billion and Counting: How Sex, Death, and Migration Shape Our World,” who was not involved with the new research.

Dr. Christopher Murray, senior author of the study and director of IHME, said there are many reasons for this shift, including increased opportunities for women in education and employment and better access to contraception and reproductive health services.

Dr. Gitau Mburu, a scientist in the World Health Organization’s Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research who wrote a comment that was published alongside the study, said in an email to CNN that economic factors such as the direct cost of raising children, the perceived risk of death to children and changing values on gender equality and self-fulfillment are all forces that may contribute to declining fertility rates. The relative contribution of these factors varies over time and by country, he added.

To maintain stable population numbers, countries need a total fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman, a number called the replacement level. When the fertility rate falls below the replacement level, populations begin to shrink.

The new analysis estimates that 46% of countries had a fertility rate below replacement level in 2021. That number will increase to 97% by 2100, meaning the population of almost all countries in the world will be declining by the end of the century.

A previous analysis by IHME published in the Lancet in 2020 predicted that the world population will peak in 2064 at around 9.7 billion and then decline to 8.8 billion by 2100. Another projection by the UN World Population Prospects 2022 predicted world population to peak at 10.4 billion in the 2080s.

Regardless of the exact timing of peak world population, it will likely begin declining in the second half of the century, Sciubba said, with dramatic geopolitical, economic and societal consequences.

‘Demographically divided world’

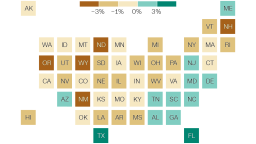

Although fertility rates are declining in all countries, the rate of decline is uneven, creating a shift in the distribution of live births around the globe, according to the analysis.

The study predicts that the share of the world’s live births in low-income regions will nearly double from 18% in 2021 to 35% in 2100. Sub-Saharan Africa alone will account for 1 in every 2 children born on the planet by 2100.

This shift in the distribution of live births will create a “demographically divided world” where high-income countries face the consequences of an aging population and declining workforce while low-income regions maintain a high birth rate that strains existing resources, according to the analysis.

“An important contribution of the study is to highlight the demographic contrast between the richest countries (with very low fertility) and the poorest countries (with still high fertility),” Dr. Teresa Castro Martín, a professor at the Institute of Economics, Geography and Demography of the Spanish National Research Council, who was not involved with the new research, said in a statement from the Science Media Centre. “Globally, births will be increasingly concentrated in the areas of the world most vulnerable to climate change, resource scarcity, political instability, poverty and infant mortality.”

Low fertility in high-income countries

On one end of the spectrum, high-income countries with plummeting fertility rates will experience a shift toward an aging population that will strain national health insurance, social security programs and health care infrastructure. They will also have to contend with labor shortages, according to the study.

The researchers suggest that ethical and effective policies that encourage immigration and labor innovations, like advancements in artificial intelligence, could help reduce some of the economic effects of this demographic shift.

The analysis also looked at the efficacy of pro-natal policies that some countries have implemented, such as child care subsidies, extended parental leave and tax incentives. The projections show an effect size of no more than 0.2 additional live births per female if pro-natal policies are implemented, which does not suggest a strong, sustained rebound, according to the study.

Although policies supporting parents may be beneficial to society for other reasons, they do not seem to change the trajectory of the current demographic shift, Murray said.

The researchers emphasize that low fertility rates and the modest effects of pro-natal policies should not be used to justify measures that coerce women into having more children, such as limiting reproductive rights and restricting access to contraceptives.

“There is a real threat in some governments trying to pressure women to have more children,” Murray said. “It’s very easy to go from encouraging women to have more children to being a little bit more coercive.”

A shrinking population poses great economic and societal challenges, but it also has environmental benefits, Mburu said.

A smaller global population could alleviate strain on global resources and reduce carbon emissions. However, increasing consumption per capita due to economic development could offset these gains, the study says.

More births in low-income countries

On the other end of the spectrum, more live births in low-income countries will threaten the security of food, water and other resources and will make improving child mortality even more difficult. Political instability and security issues also may arise in these vulnerable areas, the analysis predicts.

The predictions show that improving access to modern contraceptives and female education – two primary drivers of fertility – would reduce fertility rates and limit the increase of live births in low-income areas.

In sub-Saharan Africa, universal female education or universal contraceptive access by 2030 would result in a total fertility rate of about 2.3 in 2050, compared with 2.7 in the reference scenario, according to the study.

Additionally, these changes would contribute to women’s empowerment, which has important societal benefits, the study says.

Alternative scenarios for the future

“The main strain comes from our inability to adjust,” Sciubba said. “How do we adjust to what we have? I think that is where we really lack innovation and political will.”

Sciubba said she thinks about three alternative approaches that society can take to adapt to a shrinking, aging global population.

One scenario is the status quo world, where we go about our business as usual, maintain economic policies that rely on continued population growth and perhaps implement a few pro-natal policies that don’t make much of a difference, she said. This will not solve any of the economic and societal problems that this study outlines.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

The second scenario is a fearful world in which fear-mongering and alarmism take over and women are coerced into having more children.

And the final scenario is a resilient world, where we realize that we are not going to shift the number of children people have but instead learn to adapt our systems to the new reality, she added.

Studies like this one that model and predict global demographic changes are important, Sciubba said, because they can inform proactive planning for a resilient future. However, projections should always be interpreted with caution, she said. It is most helpful to look at the overall trends instead of the specific details.

“The most useful thing is to zoom out and say, ‘there’s no doubt there has been a shift,’ ” she said. “ ‘It’s changing, so what do we do?’ “